A few weeks ago, I read an eye-opening op-ed in the NYT:

“It’s the end of California as we know it” – By Farhad Manjoo

But lately my affinity for my home state has soured. Maybe it’s the smoke and the blackouts, but a very un-Californian nihilism has been creeping into my thinking. I’m starting to suspect we’re over. It’s the end of California as we know it. I don’t feel fine.

It isn’t just the fires — although, my God, the fires. Is this what life in America’s most populous, most prosperous state is going to be like from now on? Every year, hundreds of thousands evacuating, millions losing power, hundreds losing property and lives? Last year, the air near where I live in Northern California — within driving distance of some of the largest and most powerful and advanced corporations in the history of the world — was more hazardous than the air in Beijing and New Delhi. There’s a good chance that will happen again this month, and that it will keep happening every year from now on. Is this really the best America can do?

Now choking under the smoke of a changing climate, California feels stuck. We are BlackBerry after the iPhone, Blockbuster after Netflix: We’ve got the wrong design, we bet on the wrong technologies, we’ve got the wrong incentives, and we’re saddled with the wrong culture. The founding idea of this place is infinitude — mile after endless mile of cute houses connected by freeways and uninsulated power lines stretching out far into the forested hills. Our whole way of life is built on a series of myths — the myth of endless space, endless fuel, endless water, endless optimism, endless outward reach and endless free parking.

I realized that I didn’t know the status of either BlackBerry or Blockbuster but the sentence sounded like a remembrance of things long dead. I checked on BlackBerry. The company is not dead but it shifted from being the dominant maker of smart phones to creating software and becoming an internet security service provider. Its stock plunged from 140 in the beginning of 2008 to around 5 today. Blockbuster, meanwhile, is down to one brick and mortar store (from 9,000 in the US at its peak) but has paired up (merged) with the satellite TV provider, DISH.

Mr. Manjoo laments the increasingly frequent and ever stronger California fires and their consequences: blackouts for millions, massive evacuations, hundreds of people’s lives and properties lost, and poisoned air.

The main question is whether the author represents a single voice among the 40 million Californians—or is expressing the feelings of a significant fraction of California’s residents—when he doubts its future livability.

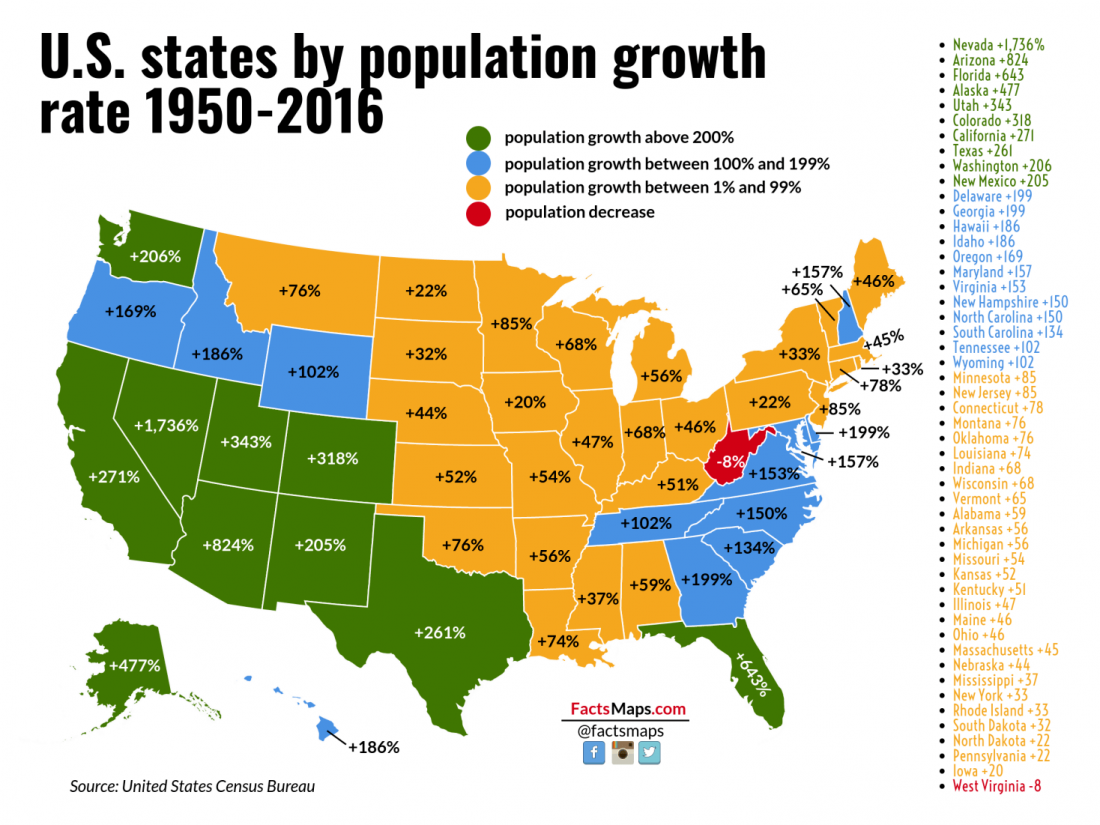

Figure 1 shows the US states’ population growth from 1950-2016. California has grown by 271%, one of the highest rates in the US.

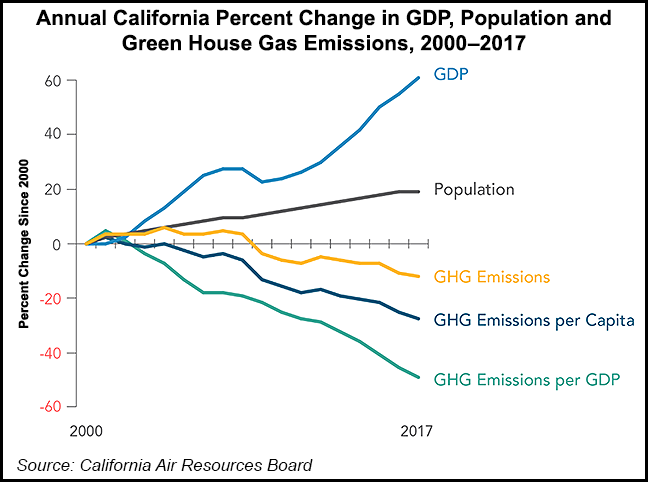

Figure 2 shows the more recent growth in population (2000-2017), GDP, and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in California. Again, the growth in population and GDP is impressive, as is the state’s decline in climate change-causing GHG emissions. The latter serves as a great example to others.

However, as we learn in our first lessons about investments, “Past performance is not a guarantee of future performance.” We know the history of California so far but we cannot make a perfect prediction with regards to its future.

One of the devastating impacts of the California fires that Mr. Manjoo cites is the PG&E utility company’s response:

In California, Pacific Gas and Electric (PG&E) cut off power to 500,000 homes in 20 counties (with more to come). More than 2 million people could ultimately be left in the dark. PG&E is testing a new strategy to avoid last year’s killer wildfires, which left 1.8 million acres scorched and more than 100 dead, after its errant power lines touched off massive infernos, the worst toll in state history.

Now, the utility is shutting off the power. PG&E, accused of neglecting its infrastructure and the flammable vegetation near its power lines, faces forests left tinder-dry by a series of brutal droughts in the past decade. As the climate dries out the West, wildfires are burning hotter, longer, and bigger than before. Overwhelmed, the utility has decided its only strategy is to stop delivery of its essential service to millions.

I wrote a blog on December 18, 2018, about the Yellow Vest demonstrations in France. While at first glance the two matters might seem unrelated, I don’t believe that is the case:

There are large similarities (at least in my mind) between how these protests started and how atomic bombs explode. With atomic bombs, people use materials such as uranium (235) or plutonium (239), which are fissile elements – meaning that if suitable particles such as neutrons hit their nuclei, their nuclei will break – and in the process, will release more neutrons that will continue the reaction. That chain, in turn, releases a very large amount of energy that can be used to either power or destroy a big city. Where does the first neutron that starts this chain reaction come from? The answer is that these neutrons are all around, mostly originating from the sun. They don’t usually cause any harm but if the right conditions exist – such as a critical mass of fissionable elements – they can demolish a city. The same sort of questionable sensitivity to an initial trigger can be seen in deadly fires such as the ones that devastated California recently. People are still working hard to figure out who triggered the fires and how. Some potential culprits include utility companies (putting wires below trees), car drivers who cause sparks on the road, barbecuing tourists, etc. The fact is that if the conditions are right for wildfires, triggers will always be available in abundance.

Both situations started with tinderbox conditions (whether metaphorical or more physical) PG&E is accused of being the random neutron that set off these large fires. This accusation triggered massive lawsuits that led to a temporary bankruptcy. The company’s remedy was to turn off the lights for massive numbers of its customers.

There was another solution that really should have been implemented long ago: utility companies ought to have buried the electrical wires underground, effectively insulating them from the dry countryside. As usual, the obstacle to this massive undertaking was cost:

In the United States, the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) Rule 20 permits the undergrounding of electrical power cables under certain situations. Rule 20A projects are paid for by all customers of the utility companies. Rule 20B projects are partially funded this way and cover the cost of an equivalent overhead system. Rule 20C projects enable property owners to fund the undergrounding

Undergrounding is more expensive, since the cost of burying cables at transmission voltages is several times greater than overhead power lines, and the life-cycle cost of an underground power cable is two to four times the cost of an overhead power line. Above-ground lines cost around $10 per foot and underground lines cost in the range of $20 to $40 per foot.[7] In highly urbanized areas, the cost of underground transmission can be 10–14 times as expensive as overhead.[8] However, these calculations may neglect the cost of power interruptions. The lifetime cost difference is smaller for lower-voltage distribution networks, on the range of 12-28% higher than overhead lines of equivalent voltage.

This particular canary in the coal mine is dead—we can see the consequences of inaction—fires and blackouts are already becoming commonplace and we must take notice. It’s past time to bury our utility lines. We cannot put the price of the future on layaway. We have to pay it now or be disconnected from the electric grid on a yearly basis. Alternatively, we could leave the state entirely but every year the impact will expand farther and farther; eventually, we will run out of places to go.

The electric wires were not the only possible triggers that were removed. Cigarette smoking bans followed:

Gov. Gavin Newsom on Friday did what two of his predecessors refused to do: He prohibited smoking and vaping in most areas of California state parks and beaches.

People caught using cigarettes, cigars, pipes or electronic cigarettes will face a fine of up to $25 under a bill signed by the governor and authored by state Sen. Steve Glazer (D-Orinda), who cited the public risk of exposure to chemicals in tobacco smoke.

While this measure is laudable both from a public health and a fire risk perspective, it will ultimately be futile with regards to the latter. Once a critical mass of burnable countryside accumulates, it is almost impossible to prevent the devastating fires by trying to eliminate possible triggers. Like the neutrons in fissionable uranium, sooner or later they will show up in some form or another.

Insurance companies make money by predicting the future and gauging the likelihood of various disasters. But they also have to pay out when something actually goes wrong. Some of these companies started to cancel insurance policies in locations that are now obviously susceptible to accelerating risk from the strong negative impacts of climate change. California quickly outlawed this practice but, “government regulators are struggling with their own conundrum: They must balance the need to protect consumers from high insurance rates with the need to keep insurance companies from going out of business entirely.”

The message: insurance companies must bear the cost of the impacts of climate change. Those companies that don’t want to carry a similar burden to that PG&E is under now have an option—leave the state completely and relocate to an environment with less risk (and most likely less reward).

The World Meteorological Organization (WMO) published the “WMO Provisional Statement on the State of the Global Climate in 2019” : the climate change impacts that are the primary causes for the high temperature and droughts that exacerbate the massive fires are accelerating:

More devastating fires in California. Persistent drought in the Southwest. Record flooding in Europe and Africa. A heat wave, of all things, in Greenland.”

Climate change and its effects are accelerating, with climate related disasters piling up, season after season.

“Things are getting worse,” said Petteri Taalas, Secretary General of the World Meteorological Organization, which on Tuesday issued its annual state of the global climate report, concluding a decade of what it called exceptional global heat. “It’s more urgent than ever to proceed with mitigation.”

But reducing greenhouse gas emissions to fight climate change will require drastic measures, Dr. Taalas said. “The only solution is to get rid of fossil fuels in power production, industry and transportation,” he said.

California is not unique in its responsibility to try to mitigate the impacts of climate change. We all have to do it and do it now. In the next series of blogs I will try to summarize how our outlooks on the economic consequences of the deteriorating climate are changing.

I wonder how bad the impact of these fires is one California’s real estate market. Many of the wealthiest people in the United States ranging from sports starts, pop stars and tech company CEO’s live there in luxurious mansions. Considering the future and if the problem gets worse, will they move to the east coast or stay on the west coast? Will there be a shift in the class of people who live in parts of California?