Previously, I described an effort to produce a film that monitors an energy transition in the Sunderban region of India. I am the “science guy” in the team and we are now working on expanding the movie to a longer version. Throughout the process, I have encountered tension with the rest of the team as to the target message.

I think the most important message for the film is this: the Indians in Sunderban are making every effort to find the most sustainable energy transition that they can afford, and that means they are turning away from coal. Most of my teammates want to target the film to what they perceive will appeal to an American audience about climate change. According to them, the American audience doesn’t care too much about the Sunderban. I encounter similar tension about climate change almost everywhere I go.

A few days ago, I went to Denver for a combined business and pleasure visit. I took with me William Nordhaus’s book, The Climate Casino (Yale University – 2013). Since I am not an economist, and Nordhaus is, this is must reading for me. The book targets American readers, but it doesn’t ignore the reality that climate change is a global issue.

The book advocates, like most of us do, that mitigation of climate change requires decarbonization of our energy supply. It focuses on an analysis of the most economical ways to achieve this. Without going into detail, the most effective way to decarbonize the energy supply is to make carbon more expensive. On a national level, the way to achieve it is either through a carbon tax (recommended amount – $25/metric ton) or selling (or distributing) emission certificates that can be traded (cap-and-trade). Nordhaus enumerates the advantages and disadvantages of both methods. He admits that mitigation will not work unless applied globally. He advocates two options: cap-and trade, similar to the mechanism advocated in the Kyoto Protocol and implemented by the European Union, or a scenario in which countries agree to “harmonize” a carbon price. He strongly favors the harmonization of carbon prices as a preferred method. Harmonization of carbon prices doesn’t take into account the enormous differences that people in India and the US pay for their energy as a fraction of their income.

On a recent trip to Australia, before the recent elections that led to a government change, one of the main issues was the implementation of a controversial carbon tax. My discussions with my Australian friends were focused on the new tax. An often heard response was that Australia is a small country that doesn’t contribute much to the changes in atmospheric chemistry that lead to climate change so why should they pay. They objected to the tax and a much more conservative government was elected.

In one of the recent episodes of the Showtime program “Years of Living Dangerously,” entitled, Under the Ice, reporter Lesley Stahl was interviewing Aleqa Hammond, Greenland’s Prime Minister. The Prime Minister was asked why Greenland was allowing the oil companies to crawl around Greenland’s fast melting coast to hunt for oil and gas that will only accelerate the melting and accelerate the consequential global sea level rise. The answer that Ms. Stahl got was that Greenland is not a frozen museum. Its people are among the poorest in Europe. They will stop the hunt if the world can provide them with suitable alternative resources for income.

My attitude is that it almost doesn’t matter what we do in the developed world. The future will be determined through the developmental pathway of the developing world. We, like everybody else, will bear the global consequences. The most effective thing that we, in the developed world, can do, is to facilitate the transition to a decarbonized economy in the developing world, while at the same time assuring their economic development. I will return to this topic repeatedly in future blogs.

Here are the important data:

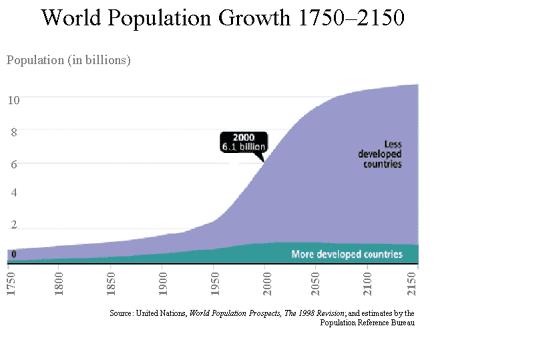

The first figure describes projections of population growth in the developed and the developing countries. Toward the end of the century, almost 90% of the world population will consist of what now we label as the developing countries.

A summary of some of the specific assumptions associated with these projections was given in earlier blogs and elsewhere.

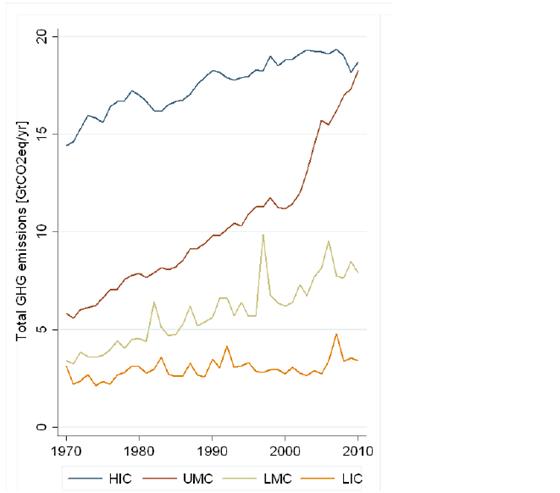

Figure 2, below, shows that the total carbon emissions of the developing countries has already surpassed the contributions from the developed countries.

Here’s what the symbols stand for: HIC – High Income Countries; UMC – Middle Income Countries – including China, Russia, Brazil, Mexico, Turkey and South Africa; LMC- Lower Middle Income – including India and Indonesia; LIC – Low Income Countries.

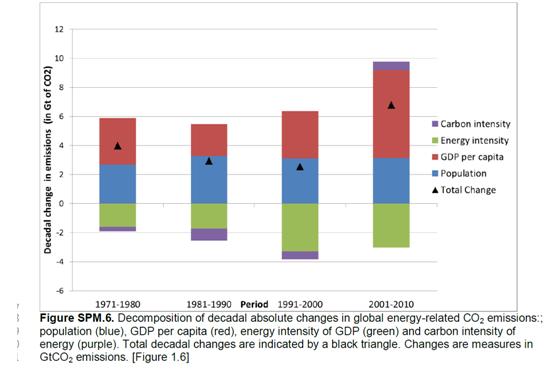

Figure 3, below, is taken from the same recent IPCC report, and it breaks down the various factors that contribute to carbon emissions. The factor that contributes the most is economic development and this will continue to be true for the forseeable future.