I am starting this blog on Friday, November 11th – the last scheduled day of the COP29 meeting in Baku, Azerbaijan. The world is waiting for a “final” draft of the conclusions. The central issue to be addressed is the amount of money that developed countries will pay developing countries to participate in mitigating climate change and adapting to the changes that are being inflicted. The preliminary figure is $250 billion per year. The cost to developing countries is estimated to be one trillion US$. As we will see later in this blog, the G20 (defined below) is trying to help. As usual, the blog will be posted on Tuesday; I will follow the developments and keep them as up to date as possible.

The mood is not cheerful. The general expectation (or hope) for the meeting is summarized in the following AP entry:

The overarching issue is climate finance. Without it, experts say the world can’t get a handle on fighting warming, nor can most of the nations achieve their current carbon pollution-cutting goals or the new ones they will submit next year.

“If we don’t solve the finance problem, then definitely we will not solve the climate problem,” said former Colombian deputy climate minister Pablo Vieira, who heads the support unit at NDC Partnership, which helps nations with emissions-cutting goals.

Nations can’t cut carbon pollution if they can’t afford to eliminate coal, oil and gas, Vieira and several other experts said. Poor nations are frustrated that they are being told to do more to fight climate change when they cannot afford it, he said. And the 47 poorest nations only created 4% of the heat-trapping gases in the air, according to the U.N.

About 77% of the heat-trapping gas in the atmosphere now comes from the G20 rich nations, many of whom are now cutting back on their pollution, something that is not happening in most poor nations or China.

A final agreement, between the developed countries and the developing countries, was announced in the early hours of Sunday (Azerbaijan time, late Saturday NYC time) (UN Climate Change Conference Baku – November 2024 | UNFCCC). The summary and the link to the full agreement are given below:

The UN Climate Change Conference (COP29) closed today with a new finance goal to help countries to protect their people and economies against climate disasters, and share in the vast benefits of the clean energy boom. With a central focus on climate finance, COP29 brought together nearly 200 countries in Baku, Azerbaijan, and reached a breakthrough agreement that will:

- Triple finance to developing countries, from the previous goal of USD 100 billion annually, to USD 300 billion annually by 2035.

- Secure efforts of all actors to work together to scale up finance to developing countries, from public and private sources, to the amount of USD 1.3 trillion per year by 2035.

Known formally as the New Collective Quantified Goal on Climate Finance (NCQG), it was agreed after two weeks of intensive negotiations and several years of preparatory work, in a process that requires all nations to unanimously agree on every word of the agreement.

You can find the advance unedited versions of the decisions taken at the Baku UN Climate Change Conference here.

The reactions to this agreement by the new Trump administration, which will take over on January 20, 2025, are anybody’s guess.

The G20 mentioned above is defined in Wikipedia as:

The G20 or Group of 20 is an intergovernmental forum comprising 19 sovereign countries, the European Union (EU), and the African Union (AU).[2][3]

The G20 scheduled its meeting in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, to take place parallel to COP29. It also tried to address the same issue of climate finance and made a recommendation to match the cost:

November 19, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil – The G20 Leaders’ Summit released its final communique on Monday night (18/11). Although the declaration reaffirms the need for trillions of dollars in climate finance and ‘hopes for a successful new climate finance goal at COP29 in Azerbaijan’ by the end of this week, it fails to specifically call for the public, grant-based finance that is an integral demand of developing countries in ongoing negotiations. While G20 governments mentioned the importance of the Paris Agreement to limit global heating, and the commitment made at COP28 to phase out fossil fuels and triple renewable energy capacity by 2030, it also failed to specifically mention the urgent need to phase out fossil fuels in their communique.

People around the world are demanding that governments commit to at least $1 trillion a year for quality climate finance at COP29 – with activists taking to the streets in over 26 countries over the weekend. In coordinated marches, thousands of people expressed their demand for climate justice, creative, collective and guerilla actions in cities like Rio de Janeiro, Paris and Munich put Billionaires in the spotlight, demanding that governments Tax Their Billions to unlock huge sums to tackle the climate crisis.

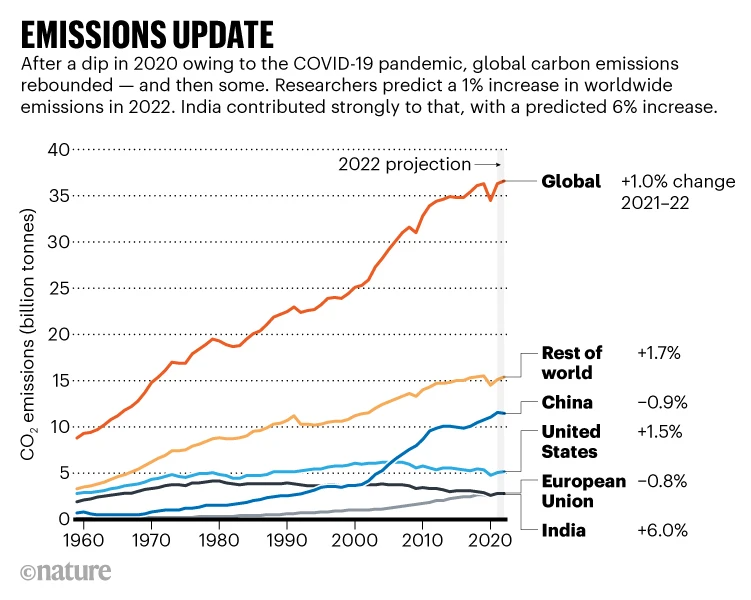

As Figure 1 shows, the recent, post-pandemic, carbon dioxide emissions in the developed world (Europe and US) are decreasing, but global emissions are continuing to increase. Emissions do not know boundaries, so to fight climate change, the world needs for developed countries with valuable resources to grow their economies by shifting to sustainable energy sources. To do this without hurting their populations, they need help.

Figure 1 – Global carbon emissions (Source: @Nature on X)

As was mentioned earlier (December 12, 19, 2023 blogs), the previous COP (COP28), which was held also in a petrostate, finally recommended that the world replace fossil fuels with non-polluting sustainable sources. However, the past year didn’t show any adherence to this trend. Countries promised to ditch fossil fuels. Instead they’re booming:

When nations at last year’s global climate conference historically agreed to transition away from coal, oil and gas, Australia’s climate minister predicted that the “age of fossil fuels will end.” Norway’s foreign minister lauded countries for at last tackling the climate crisis “head-on.” President Joe Biden said the deal put the world “one significant step closer” to its climate goals.

But one year later, these same wealthy countries are undercutting it, by scaling up exports and launching new fossil fuel projects that could last for decades. At the same time, major oil companies have weakened their climate pledges.

As world leaders gather Monday in Azerbaijan to open COP29, the moves are fueling a sense among scientists and policy professionals that the world has squandered a crucial year and raising questions about how effectively the annual U.N. climate conference can address this core part of planetary warming.

The NYT offers an explanation: Why Oil Companies Are Walking Back From Green Energy:

BAKU, Azerbaijan — When oil and gas companies made ambitious commitments four years ago to curb emissions and transition to renewable energy, their businesses were in free fall.

Demand for the fuels was drying up as the pandemic took hold. Prices plunged. And large Western oil companies were hemorrhaging money, with losses topping $100 billion, according to the energy consulting firm Wood Mackenzie.

Renewable energy, it seemed to many companies and investors at the time, was not just cleaner — it was a better business than oil and gas.

“Investors were focused on what I would say was the prevailing narrative around it’s all moving to wind and solar,” Darren Woods, Exxon Mobil’s chief executive, said in an interview with The New York Times last week at a United Nations climate conference in Baku, Azerbaijan. “I had a lot of pressure to get into the wind and solar business,” he added.

Mr. Woods resisted, reasoning that Exxon did not have expertise in those areas. Instead, the company invested in areas like hydrogen and lithium extraction that are more akin to its traditional business.

Wall Street has rewarded the company for those bets. The company’s stock price has climbed more than 70 percent since the end of 2019, lifting its market valuation to a record of nearly $560 billion in October, though it has since fallen to about $524 billion.

Many in the general public feel like the COP meetings—and their requirement of unanimous decisions—might reach the stage of obsolescence. In the mean time, however, attendance is booming:

Over 50,000 people are gathered in Baku, Azerbaijan, for the United Nations climate conference known as COP29. This is the second largest of the annual gatherings in their history, according to official estimates and recently published data.

As climate change has captured global attention, the U.N. conference has evolved from a relatively small gathering of diplomats into a major world summit, with growing delegations from developing countries that produce fossil fuels and are particularly vulnerable to their pollution.

The next blog will try to explore how the next four years of Trump’s presidency in the US will impact the energy transition.