January 27th was both International Holocaust Remembrance Day (IHRD) and the beginning of a new semester at my school (Brooklyn College of CUNY). To commemorate the day, my school invited me to speak about my Holocaust experiences and explain how they tie in with my teaching. My talk was the first in a BC series of “We Stand Against Hate” seminars, which will also address diversity and equity within Brooklyn College, Japanese American Internment Day of Remembrance, Jewish refugees in Shanghai, and Indigenous people, among other topics

President Michelle Anderson’s “We Stand Against Hate” series has been a campus fixture since spring 2017. Throughout the year, the initiative often features lectures, workshops, concerts, programs, and events that reflect our ongoing commitment to elevating dialogue, enhancing understanding and compassion, and celebrating the voices that make up our diverse campus community.

In my talk, “When the Past Writes the Present: From Holocaust Survival to Climate Change,” I tried to echo my goals here on this blog: connect my early life experiences of the Holocaust with a warning about the global consequences of unmitigated climate change.

During the question and answer period following my talk, one of my friends and colleagues—a professor in the Judaic Studies Department in my school—brought up the Biblical flood.

I had seen this analogy before, in Jonathan Safran Foer’s book, We Are the Weather. It includes a small chapter, “The Flood and the Ark,” in which the author describes a series of collective suicides in Jewish history in spite of the fact that Judaism forbids the act.

He mentions the Siege of Masada as one of the largest mass suicides in Jewish history (Masada is now the number one tourist attraction in Israel). Our knowledge of Masada comes to us mainly through the writings of Flavius Josephus, who described it as a full collective suicide: the Jews decided they would rather die than submit to the invading Romans. Foer follows the subject with a look at the Warsaw Ghetto uprising in 1943. I was there as a baby and most of my family was murdered during this event. We know about the Ghetto uprising in large part from the Oneg Shabbat milk cans, Emanuel Ringenblum’s ingenious information storage system. The people didn’t directly commit suicide in either case—i.e. they didn’t kill themselves.

In Masada they killed each other en masse. In the Warsaw Ghetto, to my knowledge, nobody killed himself or arranged for somebody else to do so but all those who rose up knew that they would ultimately be unsuccessful and be crushed brutally. The uprising started on April 19, 1943 and ended with the burning of the Ghetto on May 16th, 1943.

The Germans invaded Poland at the start of WWII on September 1, 1939 and the last resistance was recorded on October 6th of the same year. It lasted only a few days longer than the one in the Ghetto. That Ghetto uprising came in the wake of the Great Deportation, where—between July and September 1942—about 300,000 Jews were deported to and murdered at Treblinka with no resistance from any party. That uprising was not a suicide; it was a resistance meant to show that the murder of Jews could have a price.

From these two examples of uprising/suicide, the book moves to two current attempts to store collections of thousands of samples of DNA in case a global cataclysmic event destroys present life on this planet. One such storage space is the Svalbard Global Seed Vault in Norway, which got some press recently when it flooded with melting snow. There is another facility under construction: the “Noah’s Ark” at the Moscow State University. Given the name of the latter and the aims of both, it was not a stretch to consider the biblical flood and Noah’s Ark, which was, itself, constructed as a sort of living bank of DNA samples.

1859 German Drawing of Biblical Genesis Flood and Noah’s Ark

The story of the cataclysmic flood shows up in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, and as early as the epic of Gilgamesh. Wikipedia gives good sources for related stories—including some geological indications that some accounts of these events have seeds in the physical history of Earth.

Jonathan Safran Foer brings it up mainly to make the point that it took Noah considerably longer to build the ark than we have in a projected business as usual scenario before the climate change-fueled floods advance in full.

I strongly suspect that my Judaic studies friend explored the concept at a considerably deeper level than the element of DNA preservation. According to the Bible, the flood came about as a sort of attempt to “reverse” creation because God wasn’t happy with the end result of his first draft. In other words, mankind’s sins brought down the wrath of God. But God didn’t like this solution either and after the flood He made a deal with Noah not to repeat the exercise

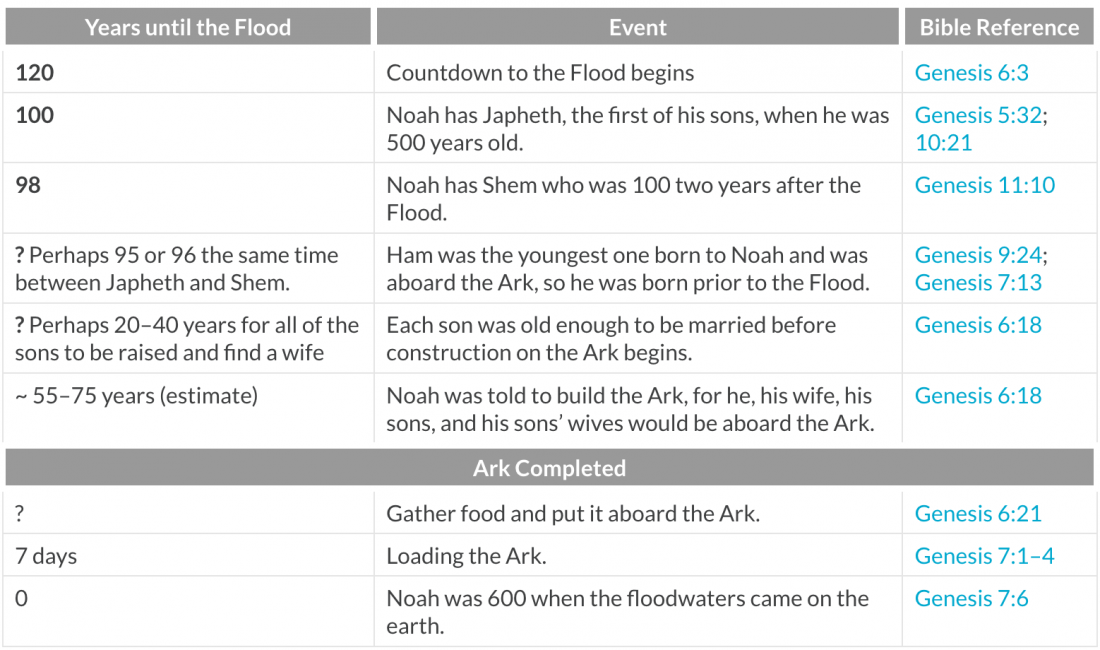

It is, however, interesting to guess how long it took Noah to build the ark. There are countless estimates available. For example:

Accordingly, this would mean it took him 100 years to build the ark, a number that almost precisely matches the estimated time it will take us to build the mitigation and adaptation infrastructures necessary to counter our own extinction—but longer than we actually have to act.

To my shame, in spite of having the Jewish Bible as an important anchor in my education, I had never made the connection before.

I want to thank my Judaic studies friend for putting me on the right track.