Many people blame Hillary Clinton’s 2016 loss on her description of half of Trump’s supporters as “deplorables,” a term under which she included people who are racist, sexist, homophobic, xenophobic, Islamophobic, etc. One word she didn’t include in her description is irrational. In a blog titled “Human Reactions to the Climate Shift” (November 1, 2022), I accused unspecified people of irrationality based on their rush to move to states with projected high climate change impacts. I used Arizona as an example. This blog is a continuation of that theme, using contrasting trends in NYC and Florida as examples.

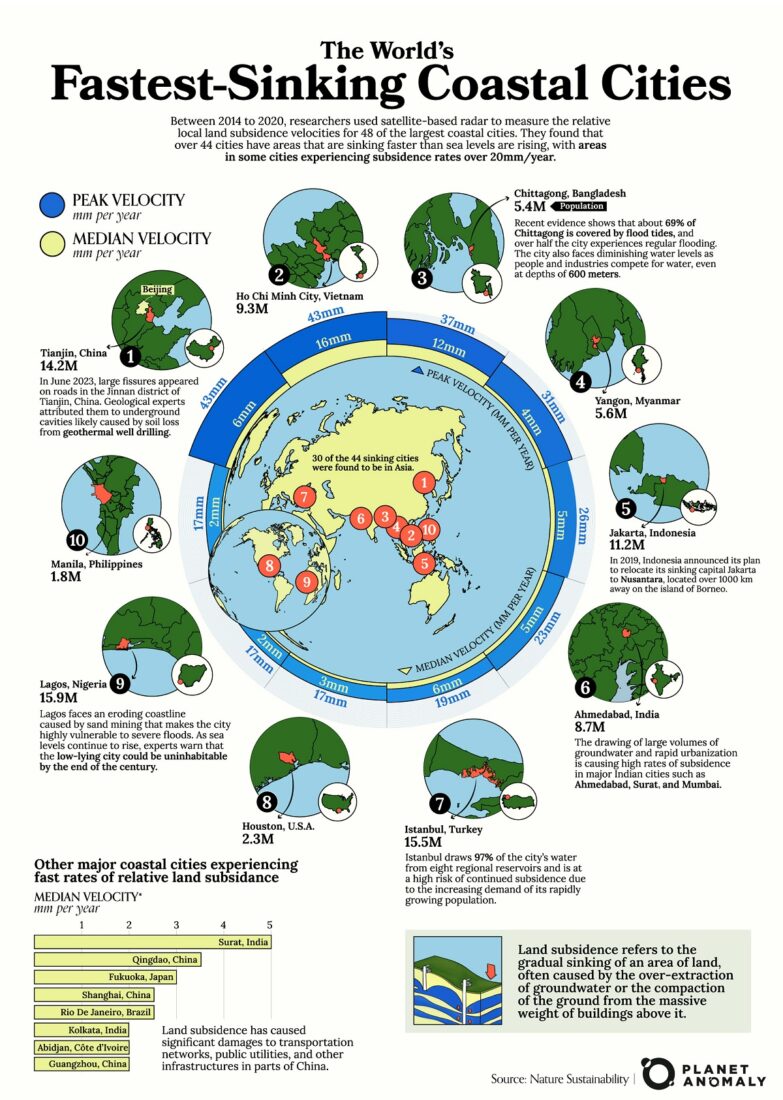

Figure 1 ranks major coastal cities around the world based on their vulnerability to sinking due to human-caused issues. The infographic clarifies, “Land subsidence refers to the gradual sinking of an area of land, often caused by the over-extraction of groundwater or the compaction of the ground from the massive weight of buildings above it.” One American city is on the list of the top 10 most vulnerable. Houston, Texas is number 8, with a peak subsidence velocity of 8mm/year and a median velocity of 3mm/year. The government of Indonesia has already decided to move the capital from Jakarta (number 5 on the list) to a much less vulnerable location.

Figure 1 – The world’s 10 fastest-sinking coastal cities (Source: Visual Capitalist)

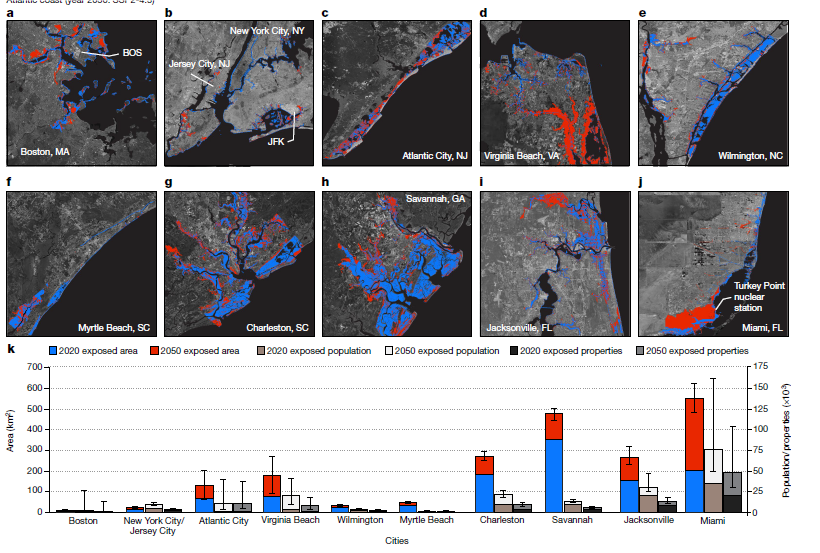

Figure 2, below, is taken from a Nature paper that shows new estimates for coastal sinking in the US, using new estimates of sea level rise. The cities shown are: Boston, MA; NYC, NY/Jersey City, NJ; Atlantic City, NJ; Virginia Beach, VA; Wilmington, NC; Myrtle Beach, SC; Charleston, SC; Savannah, GA; Jacksonville, FL; and Miami, FL. One can see that the prospects for Florida (especially Miami) are not encouraging. The prospects for New York City are significantly better.

Figure 2 – 10 East Coast US cities most exposed to sea level rise. (Source: Nature)

On the graph, each city is characterized by three columns (from left to right: areas, population, and properties exposed to sea level rise). Each column is additionally divided into two segments (data for 2020 on the bottom and 2050 on top).

A recent NYT op-ed by Vishaan Chakrabarti, titled, “How to Make Room for One Million New Yorkers,” describes an architectural plan to considerably increase living space in New York City without using areas prone to flooding. Figure 3 shows the unused areas in the plan. The essence of the plan is summarized below:

We found a way to add more than 500,000 homes — enough to house more than 1.3 million New Yorkers — without radically changing the character of the city’s neighborhoods or altering its historic districts.

Next, we excluded parts of the city that might be at risk of flooding in the future.

In the remaining areas, we identified more than 1,700 acres of underutilized land: vacant lots, single-story retail buildings, parking lots and office buildings that could be converted to apartments.

Figure 3 – Areas of proposed new housing (Source: NYT)

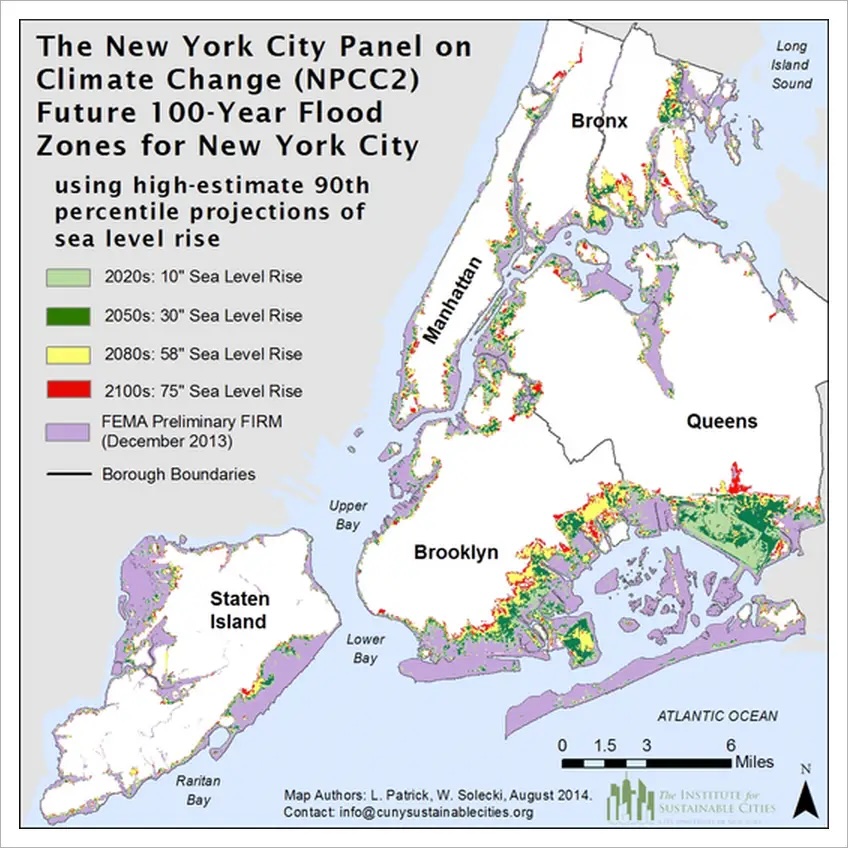

For reference, the flood map of NYC looks like this:

Figure 4 – NYC flood map (Source: Business Insider)

In contrast to the NYC plan, Figure 5 shows an area of Miami, Florida where some American billionaires have built houses. A quick look at it, combined with the data in Figure 2, makes its vulnerability to floods obvious.

Figure 5 – Miami’s “Billionaire Bunker” (Source: Forbes)

Below is a description of the area:

Locally known as “Billionaire Bunker”, Indian Creek Island on Biscayne Bay on the backside of Miami Beach is by almost every measure the most exclusive, secure, and celebrity-saturated residential enclave in America (sorry Hamptons and Palo Alto). If it had its own zip code, it would be the most expensive as well, with most properties trading hands these days for north of $40 million.

The trend of moving to Florida is not restricted to billionaires:

Freudman is one of many people who have moved to Florida in recent years. The state’s population grew 1.9% from 2021 to 2022, according to Census Bureau estimates, making it the fastest-growing state in the country. Warm weather, more affordable housing, and the lack of a state income tax are among the perks drawing movers to Florida. But some newcomers say there are also downsides to the Sunshine State, including high insurance and healthcare costs, severe weather, and a “vacation feel” that eventually wears off.

While Freudman and his wife Eva don’t regret their move, he said they’re torn on whether they want to stay in Florida long-term, particularly if they have children.

These areas that are especially vulnerable to climate change are already seeing impacts that might slow Florida’s attraction to newcomers. Home insurance bills are going up and coverage is going down:

Mark Friedlander, a spokesman for the Insurance Information Institute, a trade group, said home insurance premiums had cumulatively risen 32 percent from 2019 to 2023, while rebuilding and replacement costs had gone up 55 percent. Analysts for the group estimated that in 2023, home insurers experienced their biggest underwriting loss — the difference between collected premiums and paid-out claims — since 2011. Behind the loss were huge storms that caused more than $50 billion in damage that insurers had to pay for.

The housing market in Florida is already in trouble and the sale of condos is dramatically falling:

…even as prices dropped in some of its major metros and the number of “motivated” sellers in the state—those willing to accept a lower offer in order to sell quickly—is currently the highest in the country.

House prices at the state level have been steadily growing in the past months, with the median sale price for all homes in Florida being $404,100 in January, up 4.5 percent year-on-year, according to Redfin data.

Whether these trends indicate a return to rationality within US internal migration remains to be seen.