Figure 1 – “Dirty” vs. “clean” energy sources (Image source: RIFS Potsdam)

Conflicts are the natural consequence of every major collective transition. Our current global energy transition, which was set in motion to alleviate the deadly threats and present damage of global climate change, is no exception. Each of these conflicts comes with winners and losers. In democratic societies, both winners and losers vote, meaning that “losers” can easily become “winners” again. In such societies, a government can be elected that will try to stop or change the transition. Most of us remember how that happened in the US eight years ago. One of the best examples of these dynamics was described in a previous blog, “Wisdom from Germany: How to Transition Away from Coal” (October 8, 2019). In that example, when Germany decided to end the use of coal to power its electric grid, it compensated coal-dependent states, most of which were part of East Germany before unification.

Today’s blog will return to this issue with a focus on the US.

The most obvious conflict between winners and losers in the energy transition is the conflict between the oil and gas industries and, hopefully, the rest of us. The article,“Oil and Gas Companies Are Trying to Rig the Marketplace” summarizes the issue. A central paragraph is given below:

But as renewables have become a more formidable competitor, we are now seeing something different: a large-scale effort to deceive the public into thinking that the alternative products are harmful, unreliable and worse for consumers. And as renewables continue to drop in cost, it will become even more critical for policymakers and others to challenge these attempts to slow the adoption of cheaper and healthier forms of energy.

The simplest way that “winners” can fight “losers” is to sue them. In this case, we can count the state of Michigan as the winner and the fossil fuel industry as the loser. This is what the state of Michigan is trying to do:

Attorney General Dana Nessel announced her intent to sue the oil and gas industry in May, saying the industry profited while knowingly selling products that cause climate change. Nessel is requesting a special assistant attorney general. Her office is searching for attorneys at private law firms with previous experience pursuing similar claims.

According to GLISA, temperatures in the Great Lakes region have jumped 2.3 degrees since 1951, and predict temperatures will continue to climb at least an extra three degrees by 2050. Climate experts say the warmer weather has caused Michigan to have stronger storms, more invasive species, and algal blooms, which have resulted in the state spending millions of dollars cleaning up. However, the Attorney General’s office believes it should be the fossil fuel industry footing the bill.

About 20 other US states are trying to do the same.

But the losers have their own political backing and they are trying to block such suits:

Far-right fossil fuel allies have launched a stunning and unprecedented campaign pressuring the supreme court to shield fossil fuel companies from litigation that could cost them billions of dollars.

Some of the groups behind the campaign have ties to Leonard Leo, the architect of the rightwing takeover of the supreme court who helped select Trump’s supreme court nominees. Leo also appears to have ties to Chevron, one of the plaintiffs in the lawsuit.

In Colorado, there is a similar conflict between constructing new roads or using the resources for public transport:

Today, state highway departments have rebranded as transportation agencies, but building, fixing and expanding highways is still mostly what they do.

So it was notable when, in 2022, the head of Colorado’s Department of Transportation called off a long planned widening of Interstate 25. The decision to do nothing was arguably more consequential than the alternative. By not expanding the highway, the agency offered a new vision for the future of transportation planning.

In Colorado, that new vision was catalyzed by climate change. In 2019, Gov. Jared Polis signed a law that required the state to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 90 percent within 30 years. As the state tried to figure out how it would get there, it zeroed in on drivers. Transportation is the largest single contributor to greenhouse gas emissions in the United States, accounting for about 30 percent of the total; 60 percent of that comes from cars and trucks. To reduce emissions, Coloradans would have to drive less.

In Virginia, the losers are trying to limit rooftop installations of solar cells (Also, see April 2024 blogs on this issue):

Four years ago, Fairfax County, Virginia, unveiled an ambitions program that would bring rooftop solar systems to many schools, community centers, and park buildings in the county. Those systems would be paid for over time by reductions in the amount of money the county paid to Dominion, the utility company that services much of Virginia, including Fairfax County. Those rooftop solar installations were expected to generate up to 45 megawatts of emissions-free electricity and save the taxpayers of Fairfax County $60 million over their expected 25 year useful life.

At the time the plan was unveiled, Jeff McKay was about to become the chair of the Fairfax County Board of Supervisors. He told the Washington Post the county wanted to force the conversation on solar energy as part of a broader goal to be more aggressive about climate change related initiatives. “My theory on these environmental things is, we’re a big county; we’d better go in big and set an example,” he said. Also, “the estimate of $60 million in savings is not insignificant. There’s no downside to doing this at all.”

Fairfax County officials say they were inspired by agreements in other jurisdictions and by environmental activists. The inclusion of nearly 90 schools in the county’s initiative was due in large measure to a group of student activists — especially those at James Madison High School in Vienna who had lobbied for solar energy for several years.

But the plan did not sit well with Dominion, which, like many large investor-owned utilities, has a vested interest in selling as much electricity at possible — and limiting the ability of others to horn in on its territory. It argues that plans like this unfairly raise utility rates for others, especially low-income residents, because the $60 million the county saves will have to be made up somehow, most likely by raising rates for residential subscribers. The plan moved forward, however, until Dominion found a way to impose its will on the process in 2022. That’s when it came up with a scheme to shut the process down. How did it do that? By suddenly demanding exorbitant fees to connect rooftop solar projects like those in Fairfax County to the grid. All across Virginia, the company began requiring upgrades for a “direct transfer trip,” a device which automatically disconnects a system from the grid, on some projects. Doing so requires laying a dark fiber optic transmission line to a substation at a cost of $150,000 to $250,000 per mile, and in some cases adding a relay panel that costs $250,000 for projects exceeding 250 kilowatts. The requirement raised the costs of projects like those in Fairfax County by 20 to 40 percent.

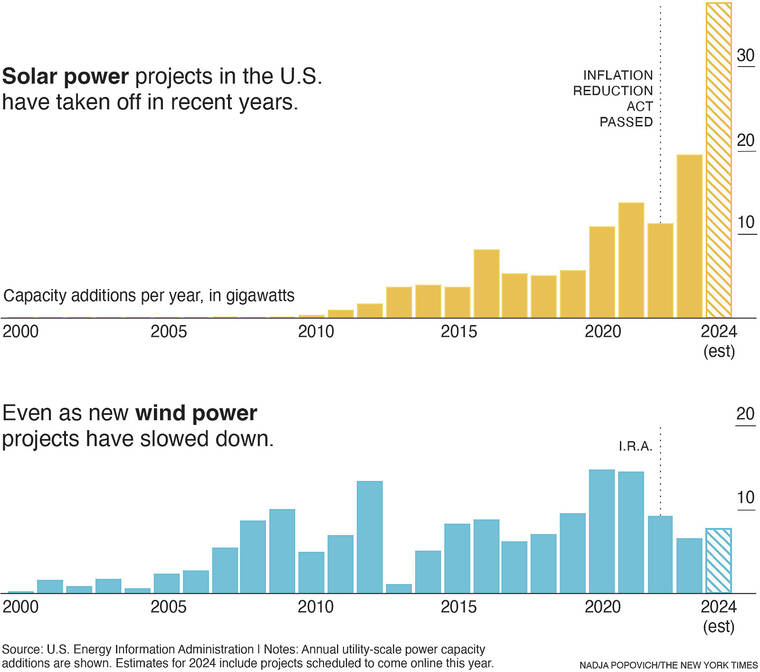

Even within sustainable energy alternatives, there is now a conflict between solar and wind power, even though both are forms of solar energy.

Figure 2 – Capacity addition to the electrical grid in gigawatts (Source: Hawaii Tribune Herald).

We need to learn from the Germans that a good way to make progress is to try to make the losers smile. In other words, perhaps those in power might find it beneficial to compensate the “loser” fossil fuel companies in some way—or at least stop vilifying them.