(Source: ResearchGate)

The IPAT identity is a central feature of every sustainability discussion. Just put the acronym into the search box to see this blog’s coverage of the topic. Three previous blogs stand out. The post from November 26, 2012, “Tackling Environmental Justice: a Global Perspective,” provides the background description:

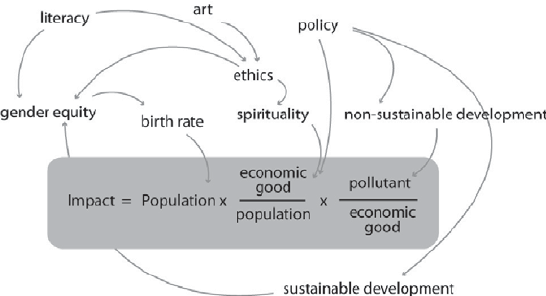

There is a useful identity that correlates the environmental impacts (greenhouse gases, in Governor Romney’s statement) with the other indicators. The equation is known as the IPAT equation (or I=PAT), which stands for Impact Population Affluence Technology. The equation was proposed independently by two research teams; one consists of Paul R. Ehrlich and John Holdren (now President Obama’s Science Adviser), while the other is led by Barry Commoner (P.R. Ehrlich and J.P. Holdren; Bulletin of Atmospheric Science 28:16 (1972). B. Commoner; Bulletin of Atmospheric Science 28:42 (1972).)

The identity takes the following form:

- Impact = Population x Affluence x Technology

Almost all of the future scenarios for climate change make separate estimates of the indicators in this equation. The difference factor of 15 in GDP/Person (measure of affluence), between the average Chinese and average American makes it clear that the Chinese and the rest of the developing world will do everything they can to try to “even the score” with the developed world. The global challenge is how to do this while at the same time minimizing the environmental impact.

Most of the previous examples in this blog have focused on the emissions of carbon dioxide and the resulting anthropogenic climate change. One good example can be seen in the May 31, 2022 blog, “Electric Utilities Through the Lens of the IPAT Identity,” which uses the IPAT form as:

- CO2 = Population x (GDP/Capita) x (energy/GDP) x (Fossil/Energy) x (CO2/Fossil)

Equations 1 and 2 consider CO2 as the impact and GDP/Capita as the affluence, while the next three terms in Equation 2 represent the technology. It was shown before that if the proper units are used in both equations, they become an identity: something that is always true, regardless of the values plugged in.

The May 31, 2022 blog analyzed the impact of electric utilities on

||the identity. Meanwhile, the June 29, 2016 blog analyzed how the ongoing rise in CO2 emissions and decline in global fertility impact the identity.

The reference and the figure at the top of this blog expand the relationship to almost everything. The price that we are paying for this expansion is the loss of the identity nature of the equation and the conversion of the identity from an objective, irrefutable truth to a subjective opinion.

Recent press reports have started to pay more attention to the declining global fertility rate, which means that we are approaching a global population decline. I have often heard and read the opinion that since population is an indicator on the right side of the identity, population decline will be followed by an emissions decline, resulting in a decrease in the impact of climate change. The opinion generally was that such a change is “good” for the world. Such an opinion does not take into account that the decline in population required for such changes in the global demographic are not taken into account in the identity. This is just one example of the prevailing opinion that the IPAT identity is not without its controversies. A summary of these is given by AI (through Google):

Critisism of IPAT and analysis of terms in terms of good or bad.

The IPAT equation (environmental impact = population * affluence * technology) has been criticized for several reasons, including:

- Simplicity

The equation is too simplistic to address complex problems.

- Interdependencies

The equation assumes that the three factors operate independently, but they may interact with each other.

- Averaging

Averaging the operands of the equation can destroy critical information and lead to information loss.

- Ecological fallacy

Averaging affluence and technology assumes that all members of the population operate identically.

- Technology

Technology cannot be properly expressed in a unit, and the value of the ratio depends on other factors.

- Differences between rich and poor

The equation doesn’t account for the vast differences between rich and poor.

- Individualist and consumerist approach

The equation predisposes the formula to an individualist and consumerist approach to solving environmental impact.

The main advantage of the wide use of the identity is that if it is run as an identity and not as an “opinion,” it can be quantified and can serve as a starting point for global trends.

The purpose of this blog is to extend the IPAT to the new global trends that were discussed in previous blogs this year (April 16th, August 13th and August 20th) that started in my lifetime and will continue to dominate the reality of our children and grandchildren. These trends were explored in previous blogs in terms of their impacts on the 10 most populated countries that together constitute more than 50% of the global population. Of these, the only developed country is the USA. Table 1 represents all these trends as generational (defined approximately as 25 years) changes in post WWII trends. The data for the global trends were taken directly from Google searches.

Table 1 – Generational changes in global, post-WWII trends

| Global Trends | Population

(billions) |

Affluence

(GDP in trillion US$) |

Population with access to electricity (%) | Fertility rate | Carbon emissions (tons/capita) | Production of electricity with nuclear energy (% of total production) | Share of global households with computers (%) |

| Current | 8.2 | 111 | 91 | 2.3 | 4.3 | 10 | 50 |

| 2010 | 6.9 | 67 | 83 | 2.6 | 4.4 | 13 | 37 |

As I mentioned before, the impact of the carbon emissions and the decline in fertility were analyzed through IPAT in previous blogs. Aside from population and affluence, the other three trends from this acronym will be quantified in future blogs.