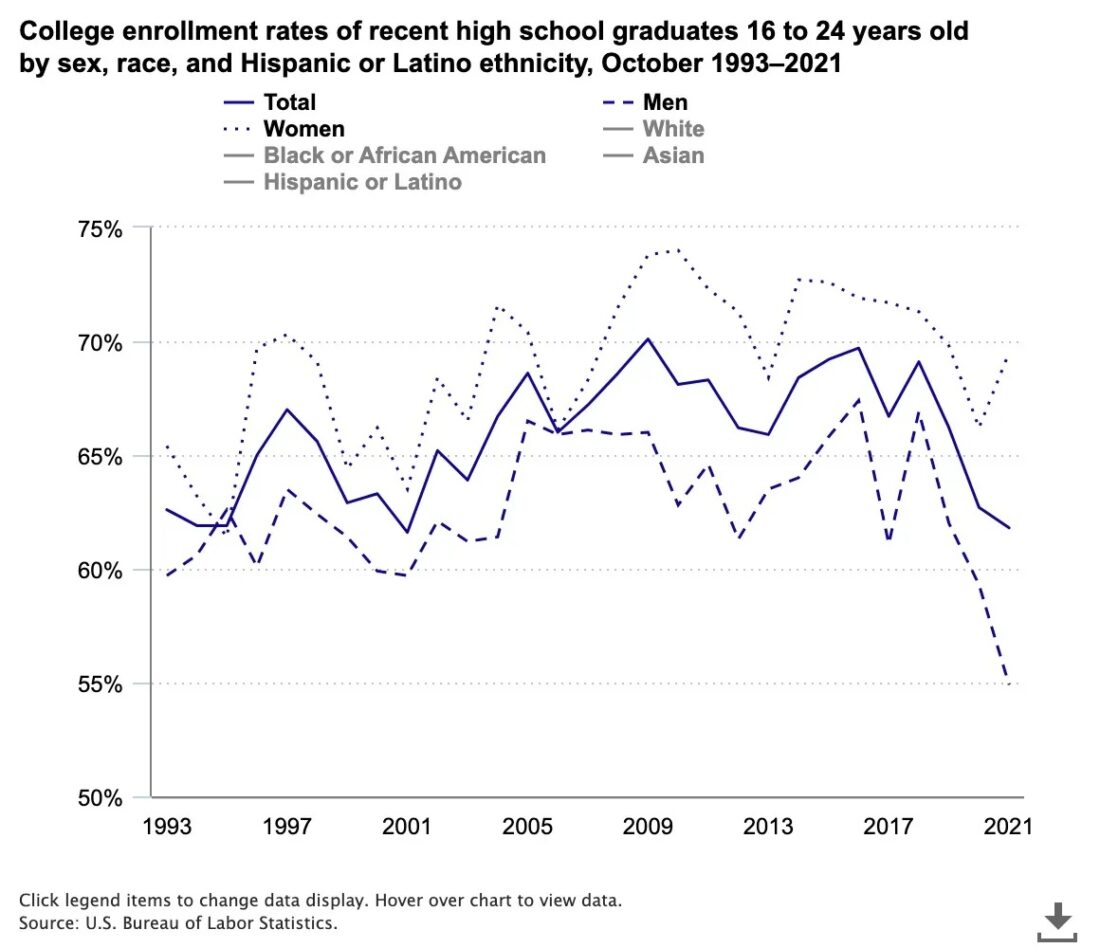

Previous blogs on the decline in college enrollment (May 30th, October 25th, and October 31, 2023) were inspired by my teaching experience. I am returning to this issue from the broader perspective with a focus on the US. This blog is focused on the data; next week’s blog will focus on changes that colleges need to make to try to adapt to our changing reality. The recent enrollment decline, separated by gender, is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 – College enrollment rates (Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics via The Week)

Forbes’ analysis shows some specifics about very recent changes:

Enrollment of 18-year-old college freshmen decreased by 5% this fall compared to last year, and now the focus is turning to understanding why the decline occurred and how it can be reversed.

The drop-off is a sharp turnaround from last year’s growth in freshman enrollment according to a new analysis, commissioned by the National College Attainment Network.

The analysis by the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center is a follow-up to its earlier report released in October that showed a 5% drop in freshmen overall and a 6% drop in 18-year-olds at the same time there was an overall 3% year-over-year increase in undergraduate students.

Overall, enrollment of 18-year-old freshmen was down 5% compared to last year, when it increased 3%. The decline was widespread, occurring in 46 states.

The enrollment decline was sharpest for white students (-10%), followed closely by multiracial students (-8.3%) and Black students (-8.2%). Asian (-5.7%) and Latino/a (-2.1%) students experienced smaller declines.

A few days later, Forbes tried to emphasize some of the consequences of these changes:

Annual college closures are likely to increase above their current rate if the anticipated decline in higher education enrollment transpires, according to a Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia working paper released this month.

Using these data, the researchers compared the accuracy of various statistical models in identifying those institutions that eventually closed. Because public institutions rarely close, the analysis was restricted to private for-profit and nonprofit two-year and four-year schools.

The best model — one that used machine learning and was able to compensate for the missing data that plagues many prediction formulas — revealed that of the 100 institutions it assessed to be at most financial risk, 84 had closed within a three-year time span.

Recent news about changes in the global population, with demographic changes in the US, is given below:

WASHINGTON — The world population increased by more than 71 million people in 2024 and will be 8.09 billion people on New Year’s Day, according to U.S. Census Bureau estimates released Monday.

The 0.9% increase in 2024 was a slight slowdown from 2023, when the world population grew by 75 million people. In January 2025, 4.2 births and 2.0 deaths were expected worldwide every second, according to the estimates.

The United States grew by 2.6 million people in 2024, and the U.S. population on New Year’s Day will be 341 million people, according to the Census Bureau.

The United States was expected to have one birth every 9 seconds and one death every 9.4 seconds in January 2025. International migration was expected to add one person to the U.S. population every 23.2 seconds. The combination of births, deaths and net international migration will increase the U.S. population by one person every 21.2 seconds, the Census Bureau said. So far in the 2020s, the U.S. population has grown by almost 9.7 million people, a 2.9% growth rate. In the 2010s, the U.S. grew by 7.4%, which was the lowest rate since the 1930s.

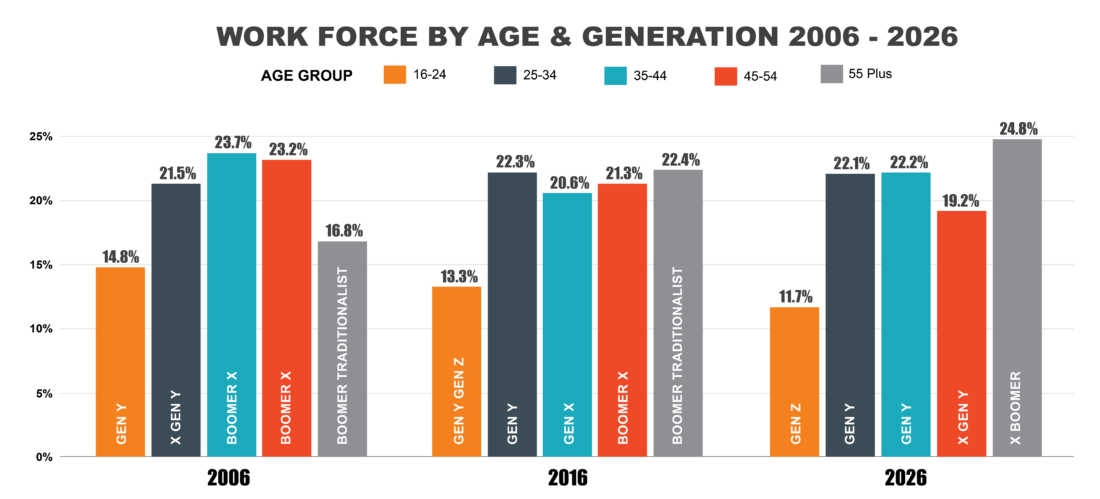

Changes in the makeup of the US workforce by generation are shown in Figure 2:

Figure 2 – Workforce by age and generation 2006-2026

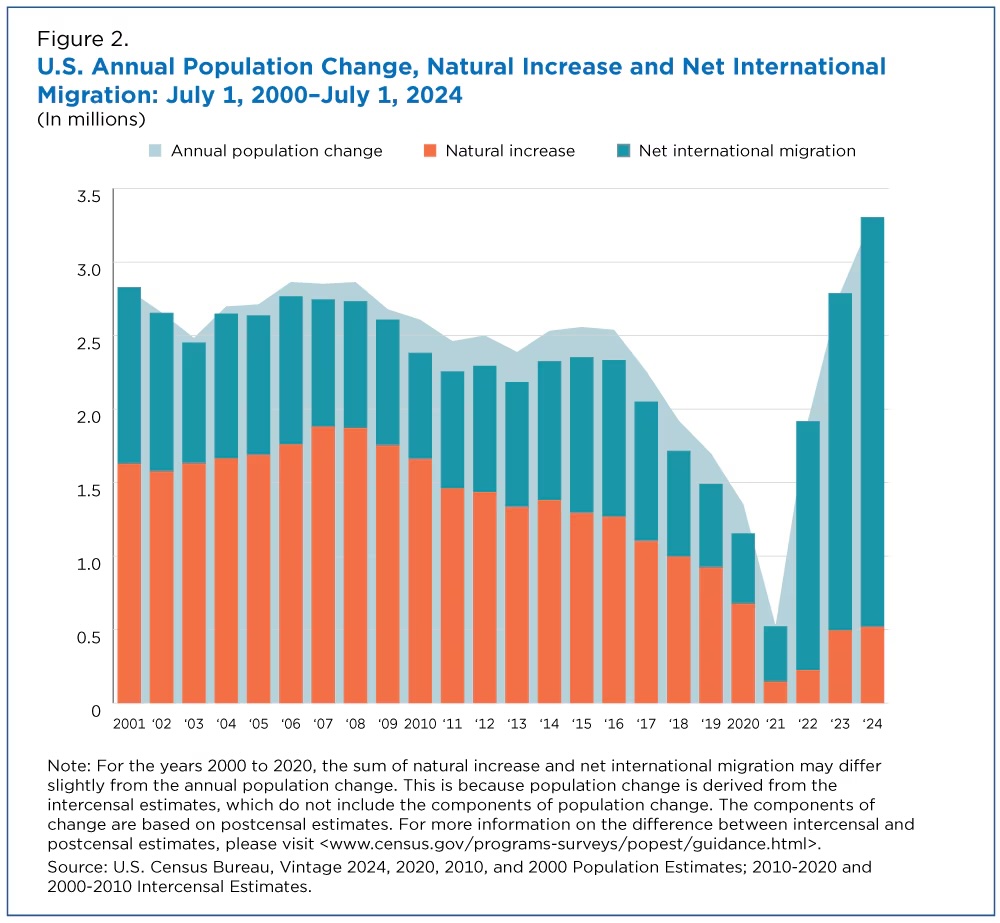

As was mentioned in earlier blogs, the fertility rate in the US is declining sharply, yet the population is still growing. The main process that feeds this population growth is immigration. The dynamics of these two processes are clearly shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3 – Population estimates (Source: US Census)

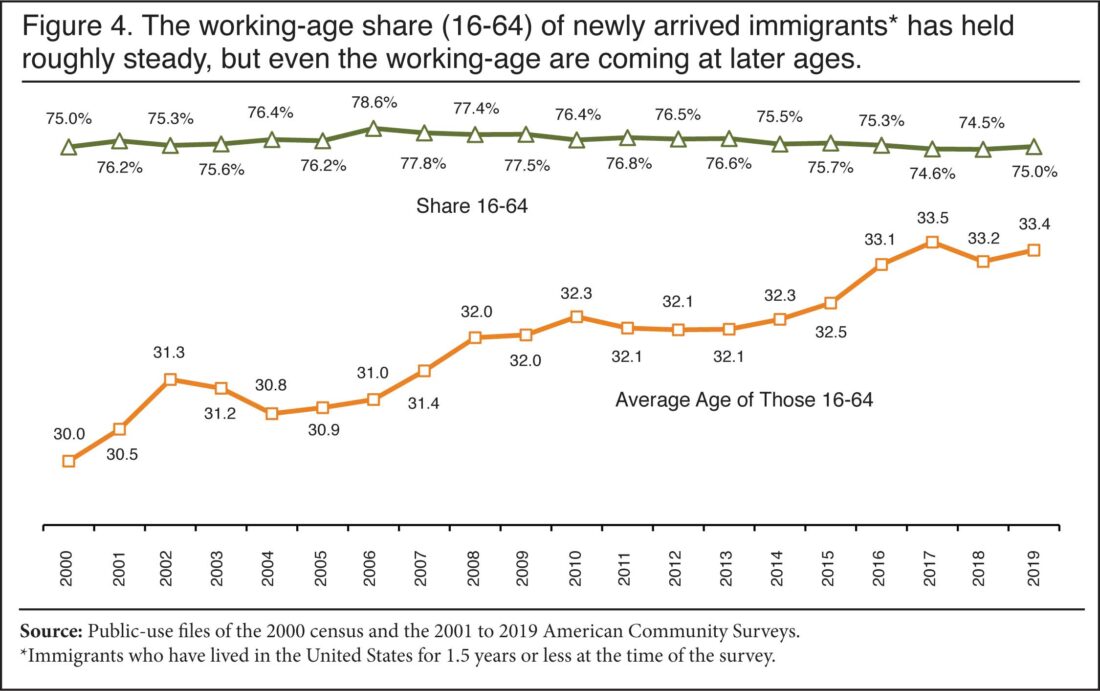

College enrollment is mainly made up of Generation Z students. The declining fertility rate ensures that the fraction of incoming freshmen will also decline. Figure 4 shows the changes in the age distribution of newly arrived immigrants; their age is sharply increasing. This dynamic is summarized in a report by the ICEF Monitor (International Consultants for Education and Fares), a summary of which is given below):

Short on time? Here are the highlights:

-

US colleges are facing a smaller pool of young domestic students due to demographics and changing views on the importance of higher education

-

The total number of domestic high school graduates is expected to peak in 2025 and then decline steadily through 2041

-

New approaches are necessary to mitigate risk and appeal to new target audiences, including an increased emphasis on international recruitment

Figure 4 – The share of new immigrants who are of working-age (defined as 16 to 64) (Source: Center for Immigration Studies)

A broader outline of the college enrollment situation is provided by AI (through Google):

Many colleges are cutting majors and programs to reduce costs and make ends meet. This includes:

- Rural universities

Universities that serve rural students are disproportionately affected by these cuts. For example, West Virginia University eliminated 28 undergraduate and graduate majors and programs, including most foreign languages.

- Budget challenges

Colleges are facing budget challenges due to a number of factors, including:

- Fewer high school graduates going straight to college

- Rising operational costs

- The end of federal COVID relief money

- Enrollment decline

College enrollment declined during the pandemic, and officials had hoped enrollment would recover to pre-COVID levels. However, enrollment figures have not recovered.

- Financial aid application overhaul

The federal government’s overhaul of its financial aid application has complicated the situation.

Major restrictions are another way colleges can limit the number of students who can enroll in a particular major. These restrictions can include requiring students to meet GPA requirements, participate in an interview, or submit a competitive application. These restrictions can create barriers for students who are less-privileged.

While large-scale cuts to majors in the years during and since the Covid-19 pandemic have gotten some attention, what many have in common has been largely overlooked: They’re disproportionately happening at universities that serve rural students or are in largely rural states.

One remedy that schools are increasingly turning to is the reexamination of the number of majors that they are offering. In the next blog I will try to go deeper into this issue.

Less than two weeks after this blog, the new Trump administration will come to power and will try to implement one of its main promises – to significantly reduce immigration. There are already significant disagreements among the followers of the new administration about the future of the H-1B visa, which is given to some of the best qualified foreign nationals. Many from outside the US mark this program as a brain drain—especially for developing countries; they will probably not be sorry to see this program curtailed. Almost all the recipients of these visas are college graduates, so curtailing these visas will not have a major impact on student enrollment but it might have an impact on faculty recruitment. Its impact on the economy remains unknown. I will try to follow this discussion.

Interesting data presented regarding the enrollment decline. The sharper drop in enrollment among white, multiracial, and Black students compared to Asian and Latino/a students raises several questions. Are perceptions of job security linked to academic field of study having a disproportionate impact? For example: perhaps some STEM courses favored by the higher enrolling populations are linked to long futures whereas traditionally popular fields of study seem more subject to automation by AI. Are we seeing shifts in career expectations driven by concerns about climate resilience in different communities? Or could perceived value vs. cost of higher education become a sticking issue.

I look forward to next week’s blog about the changes colleges need to consider. What practical adjustments can schools implement related to financial and education strategies designed to reverse downward college enrollment trends and maximize benefit from resources offered given different student population needs, concerns, interests, future financial well-being and environmental job/lifestyle compatibility? A more sustainable future benefits all!