Hello all and thank you so much for your patience. I usually try to post my blog on Tuesdays but due to some technical difficulties this week’s entry got delayed. Lately I’ve been alternating between the takeaway from my vacation and issues surrounding the presidential election. This blog goes back to my series on immigration and inequality (starting on June 21), which included two personal stories: my own (July 5) and that of Sofia Ahsanuddin (July 12).

I was born to a Jewish family three months before the Nazi invasion of Poland. I spent my first three and a half years in the Warsaw Ghetto and the two following ones in Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. I immigrated to Palestine (now Israel) with my mother when I was six years old – roughly six months after we were liberated by American soldiers.

Both of my parents were lawyers, trained in Poland. My father was murdered by the Nazis in 1943. As for my mother, in post-war Israel, Polish law was useless. Although her English was functional, she didn’t speak the language of the land. That meant that she couldn’t retrain herself in Israeli law or shift to another profession that required an academic degree. Meanwhile, she had to find way to support both of us. She continued writing books and articles in Polish but it didn’t generate much of an income so she became a secretary (officially an Executive Secretary).

When I had to choose a career path, it was natural for me to try to follow in my parents’ footsteps and study law. I was a good student and had played key roles in major simulation trials that took place in my school. Many of these trials were connected – either directly or indirectly – to the Holocaust (e.g. Should Israel accept or reject Germany’s offer of reparations, and the trial of Rudolf Kastner – I served as his defense lawyer).

My mother strongly discouraged this path. She argued that I should choose a more “global” profession: one independent of either local reality or my native language and culture. She invoked her own experience, urging me to prepare for the eventuality of something similar to a “second Holocaust” that would force me to leave my home and find a way to make a living in a foreign country with an unknown language.

Her argument won me over and I took my degrees in science. Two generations later, I am delighted with my choices. I didn’t experience a second Holocaust; I was not forced to leave Israel and immigrate to the United States. I could have been perfectly fine staying and raising my family in Israel. I had choices. I became part of the migration “elite”: I was easily accepted wherever I went and had no culture shock difficulties.

Back to the present – I came back from my recent vacation at the end of July, a week before the Rio Olympics started. I, like millions of viewers around the world, tuned in to the spectacle whenever and however I could. I also watched the 2012 Summer Olympics and wrote a blog on the London event (August 27, 2012) expressing a wish that a similar competition take place to serve the public good.

Back then, I was trying to analyze why significant fractions of the public either denied climate change or opposed mitigation efforts. One of the main factors was NIMBYism – in other words, there are many who don’t refute the phenomenon of climate change but don’t want to do anything about it.

This time, when I watched the Olympics, I focused on migration and globalization. I couldn’t escape the feeling that aside from national symbols such as flags, national anthems, and daily medal counts, almost everybody looked the same – with a few notable exceptions:

Figure 1 – Pita Nikolas Tafatofua carrying the Tonga flag in the 2016 Olympic opening Ceremony

Mr. Tafatofua is a taekwondo practitioner who was born in Australia to Australian and Tongan parents. Obviously that’s not how he dresses in everyday life but it made him stand out from the crowd and celebrated the traditions of his Tongan ancestors.

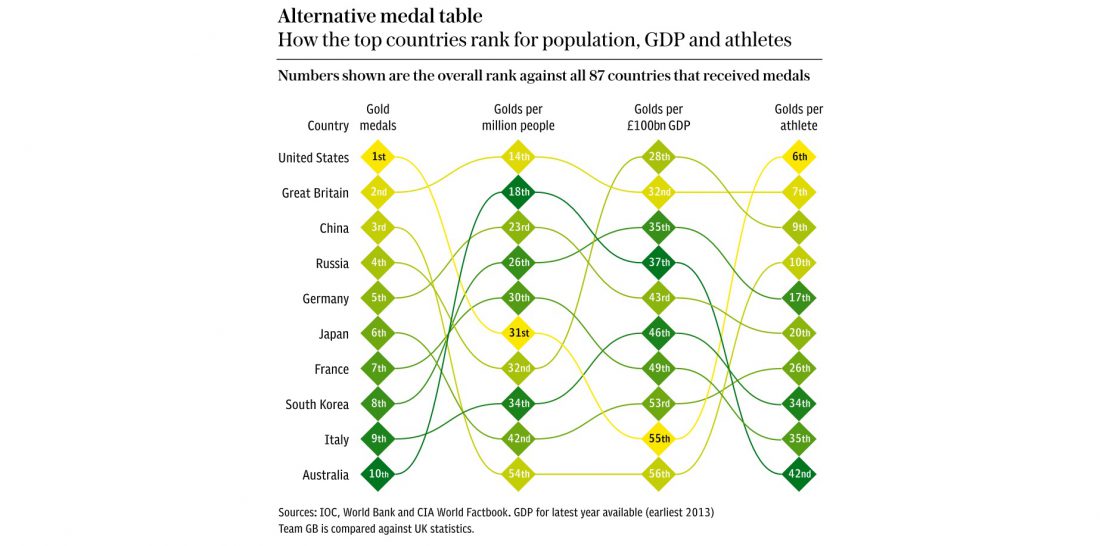

There were 11,000 participants competing in the games. Unsurprisingly, most medals were won by representatives of developed countries. However, some publications attempted to normalize the medal counts according to each country’s GDP and population – see Figure 2. By the GDP count, the US ranks 55th.

Figure 2 – Alternative medal count for the Rio Olympics

Figure 2 – Alternative medal count for the Rio Olympics

A recent NYT article showed some amazing statistics about the nationality of the Olympians:

In the last few decades, a migration of table tennis players from China has produced a full-fledged diaspora of athletes on six continents, reshaping the landscape of the sport. There were 44 table tennis players in the 2016 Olympics that were born in mainland China. Table 1 shows the countries that they represented in the Rio Olympics and Table 2 shows the percentages of foreign-born athletes in other sports.

The Olympic charter states that “any competitor in the Olympic Games must be a national of the country of the NOC which is entering such competitor.” That being said, “A competitor who is a national of two or more countries at the same time may represent either one of them, as he may elect. However, after having represented one country in the Olympic Games, in continental or regional games or in world or regional championships recognized by the relevant IF, he may not represent another country unless he meets the conditions set forth in paragraph 2 below that apply to persons who have changed their nationality or acquired a new nationality.”

Table 1 (Based on NYT article)

| Country | Mainland Chinese – Born Table Tennis Team Members, 2016 |

| China | 6/6 |

| Singapore | 5/5 |

| Australia | 3/6 |

| United States | 3/6 |

| Canada | 2/2 |

| Turkey | 2/2 |

| Netherlands | 2/3 |

| Spain | 2/3 |

| Portugal | 2/5 |

| Austria | 2/6 |

| Germany | 2/6 |

| Hong Kong | 2/6 |

| Poland | 2/6 |

| Luxemburg | 1/1 |

| Qatar | 1/1 |

| Ukraine | 1/2 |

| Republic of Congo | 1/3 |

| Slovakia | 1/3 |

| France | 1/4 |

| Sweden | 1/5 |

| Brazil | 1/6 |

| Korea | 1/6 |

Table 2

| Sport | % Born Outside the Country |

| Table Tennis | 31 |

| Basketball | 15 |

| Equestrian | 13 |

| Canoe slalom | 12 |

| Wrestling | 12 |

| Tennis | 11 |

| Rhythmic gymnastic | 11 |

| Judo | 11 |

| Gymnastic | 11 |

| Badminton | 10 |

| Golf | 10 |

| Fencing | 10 |

| Track and Field | 9 |

| Swimming | 9 |

Eighty-four American Universities trained athletes to become Olympic medalists. The top five in terms of number of medals ever won include: University of Southern California – 309 medals; Stanford University – 270 medals; UCLA – 233 medals; UC Berkeley – 207 medals and University of Michigan – 144 medals.

A significant fraction of these students were not American nationals and were furthermore representing different countries. Once you have the skills to compete on the Olympic level and want to train in a country different than yours or represent a country other than the one where you were born, national legal boundaries quickly begin to melt away.

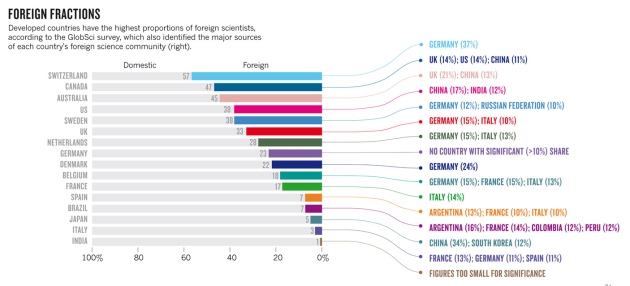

To put it briefly, the same rule applies to successful scientists. An article in the journal “Nature” (Nature, 490,326 (2012)) details the distribution of the scientific diaspora. The key figure in this article (shown here as Figure 3) includes the main countries from which the scientists have emigrated. The following paragraph, from the same publication, describes the downside of these relatively low immigration barriers:

But some countries worry that they are losing their top researchers. Of the world’s most highly cited scientists from 1981 to 2003, one in eight were born in developing countries, but 80% of those had since moved to developed countries (mostly the United States), according to a 2010 study by Bruce Weinberg at Ohio State University in Columbus. India, for example, loses out, says Binod Khadria, an economist who studies international mobility at Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi. “The best and brightest are kept in other countries.”

Figure 3 – Destination and sources of the science diaspora.

Figure 3 – Destination and sources of the science diaspora.

In other words, if you want to be a “global citizen” and see national boundaries magically melt before you, listen to my mother: get the “right” education and be very good at what you do.

The worlds strides in technology has led to a global connection like never before. The transmission of data in the blink of an eye has led to a globalization effect that not only improves are knowledge but our outcomes as a species in all fields. Globalization will be the key to making a real change in the mitigation and reversal of future horrid climate disasters because only as a whole can a difference be made.

We can’t fight against climate change and save our future without being unity as people of this world. One country can’t do everything to combat climate change while another country continues to emit carbon at a high rate. That would be counterproductive and we would make any true changes. In order for us to make true change and to save our future, we need to come together as people all around the world and combat climate change together. After all, we only have one planet we live on and saving our planet from a point of no return is in the best interest of us all.

Globalisation is essential to disseminating information and making people aware of what’s going on in the world. I would hope that that the globalisation of science and knowledge about the climate leads people to become more aware and more invested in the world and do what they can to reduce their carbon footprint and improve the world.

Globalization is the single most dominating phenomenon of our time. Never before were we able to transfer information from one part of the world to another within milliseconds. This is a complete game changer that brings us as a Human species closer than ever before. We can now experience live events that are happening any where in the world. This should be used to our advantage for us to come together as one and solve our issues unitedly rather than continuing the xenophobia that has been so dominant in the past.

Sports can bring all the countries together, and I believe that we should unite all the countries together to fight with climate change.

Hopefully, the globalization of science, can be said to be humanity’s most common language, can unite the world in fighting climate change. Once politicians start arguing about climate change more frequently and maybe voters start swaying elections because of those arguments, scientists globally will be ready to respond will appropriate research and data to help those in power to take environmental protection more seriously.

Very interesting post! I didn’t pay much attention to the Olympics except when we were sampling the Village and the Olympics stadium for our project (http://metasub.org/the-olympiome-project/). Your reference to the “brain drain” experienced by developing countries is a big concern. I sometimes wonder if I should go back to India to help in whatever way I can.

I agree. I immigrated from Grenada,W.I when I was 10 years old, prior to me coming here with my 3 siblings, our mother moved here in search of a better way of life. Since being here, I have served in the U.S. Army for 25 years and retired in 2014. Even though I am a citizen of this country, I have traveled the world becoming familiar with different cultures and I am now continuing my education in Business Administration with concentration in Human Resources which I believe would make me marketable in any country should I decide to move because there will always be a need in that market and your background would be irrelevant, as long as you meet their qualifications.