Starting on February 28th of this year, I’ve posted a series of blogs mentioning proposed remedies to the local implications of the global population’s declining trend and consequential societal aging. These include seppuku (voluntary suicide of the old) suggested by a Yale, Japanese-born professor (February 28th) as well as some more “practical” approaches in Japan:

In 2020, Japan’s health ministry launched eight “living labs” dedicated to developing nursing-care robots. Yet in a way, the entire country is one big living lab grappling with the repercussions of a rapidly aging society. In business, academia, and communities around Japan, countless experiments are under way, all aiming to keep the old healthy for as long as possible while easing the burden of caring for society’s frailest.

Also on the books are a modest increase in retirement age in France and various experiments in Russia to use payments to encourage families to have children (March 7th blog). While these are state-led measures, other approaches are more individualistic. For instance, a more recent trend in Russia, directly connected to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, is the increase in “baby tourism”:

These are just some of the Russian women who posted on popular forums for “baby tourism” – a phenomenon that has been growing since the Kremlin launched an invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.

Since then, authorities say thousands of young Russians have flown to South America, Argentina in particular, where they don’t need a visa to enter the country, and where their babies are guaranteed a less restrictive foreign passport.

The Moscow-Buenos Aires route is also an easier way for the mothers to acquire local nationality. But now officials are concerned about the sheer scale of the problem after one Ethiopian Airlines flight landed in February with 33 pregnant Russian women on board.

A Euronews investigation has uncovered the network of Russian travel agencies and support services that charge up to $35,000 (€32,840) to pregnant Russian women and make false promises that lawyers say are tantamount to criminal activity.

On the other end of the life cycle, recent trends in China suggest attempts by certain segments of the population to make money on what they consider to be unavoidable trends resulting from the aging process (Analysis: As China ages, investors bet they can beat retirement home stigma):

HONG KONG/SHANGHAI, March 3 (Reuters) – Investors are betting big on a major attitude shift among elderly Chinese – that they will warm up to retirement homes as the world’s most populous country ages and smaller families struggle to support parents and grandparents.

Who takes care of the elderly in China, where pensions are tiny, is one of the major headaches policymakers face as they deal with the first demographic downturn since Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution.

Costly nursing homes are out of reach for most elderly and are generally frowned upon, with many judging the use of such facilities as a sign children are not fulfilling their duties.

But the hope of companies investing in the sector in China is that those attitudes will change soon, and fast – at least among the small percentage of elderly who got rich before they got old. China’s 1980 to 2015 one-child policy means smaller families are expected to support the old folk, some of whom would have no choice but to seek professional elderly care, investors say.

In the US, frightening and unlawful trends are being exposed of companies relying on populating the labor force with unaccompanied migrant child workers:

These workers are part of a new economy of exploitation: Migrant children, who have been coming into the United States without their parents in record numbers, are ending up in some of the most punishing jobs in the country, a New York Times investigation found. This shadow work force extends across industries in every state, flouting child labor laws that have been in place for nearly a century. Twelve-year-old roofers in Florida and Tennessee. Underage slaughterhouse workers in Delaware, Mississippi and North Carolina. Children sawing planks of wood on overnight shifts in South Dakota.

Largely from Central America, the children are driven by economic desperation that was worsened by the pandemic. This labor force has been slowly growing for almost a decade, but it has exploded since 2021, while the systems meant to protect children have broken down.

This brings us to the issue of immigration.

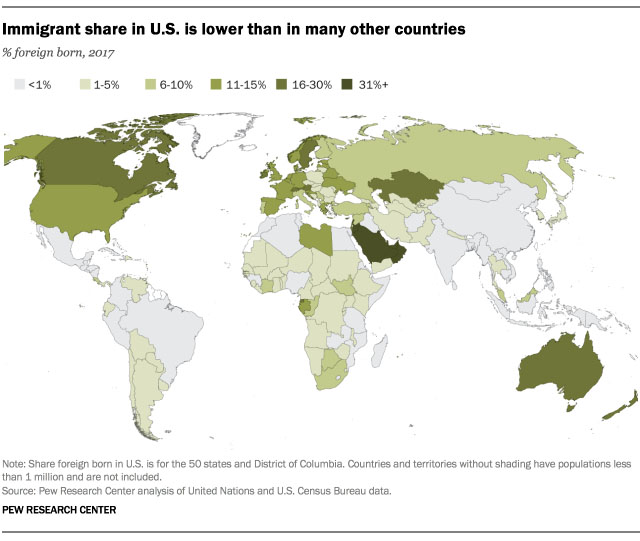

Figure 1 in last week’s blog showed that now, while there is a global trend of population decrease, the slow-down of population growth and the aging of the population are much more pronounced in developed, rich countries, than in developing ones. This dynamic opens the door for increased immigration from developing countries to developed ones. As shown in Figure 1 below, this trend is being quantified through increases in foreign-born residents in rich countries compared to developing countries. The situation in Russia in Figure 1 is a bit misleading, however, because it presumably contains many people who were born in the Soviet Union and became “foreign-born” after the USSR’s break-up in 1990.

Figure 1 – Percent of immigrants throughout the world (2017)

(Source: Pew Research Center)

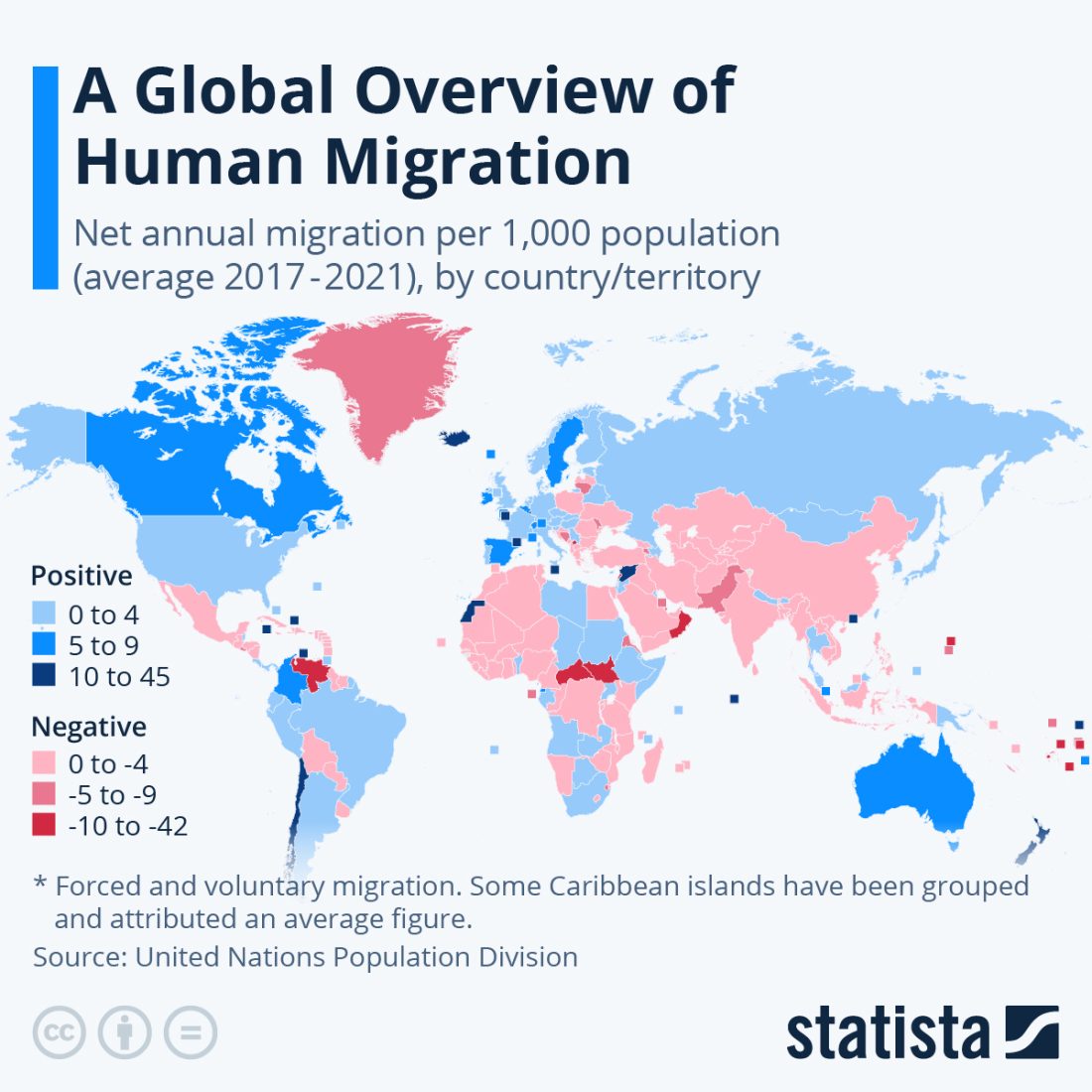

The number of foreign-born occupants shown in Figure 1 integrates over the lifetime of the immigrants. These numbers apply to anyone born elsewhere, regardless of how long they’ve lived in their current country. Figure 2, on the other hand, shows recent trends of integration, counting only those who moved over the last five years as separate; native-born and six-year immigrants are grouped together. The two show similar trends, with some noticeable differences (Saudi Arabia, the US, Canada, etc.).

Figure 2 – Global migration (Source: Statista)

Statista, the same reference from which I took Figure 2, summarizes the recent immigration situation in the following way:

This map provides an overview of the migration trends in the world. It shows the annual net migration (arrivals minus departures) of all countries and territories, relative to their population size. Between 2017 and 2021, the regions of the world that lost the largest share of people via emigration were the Marshall Islands and American Samoa in the Pacific Ocean, followed by Lebanon and Venezuela. During this period, these four territories, some of which are experiencing severe economic hardship, experienced an average net loss of 28 to 42 inhabitants per 1,000 people per year.

In contrast, the regions that attracted the most migrants relative to their population size were the New Zealand-administered Tokelau Archipelago, the Caribbean tax haven of the Turks and Caicos Islands and, in Europe, Malta. For these three places, the average annual net migration was between 22 and 45 additional persons per 1,000 inhabitants.

The site quotes 281 million international immigrants in 2020 (3.6% of the global population). The immigration issue is complicated. Put the word “immigration” into the search box above and you will get many blog posts. However, the unfortunate reality is that globally the immigration process has become highly politicized. It’s transformed some democratic countries into “illiberal” ones where bigots float “replacement” concepts that claim immigrants leave their countries to “replace” richer native-born citizens. For a long time, immigration policies were tailored to attract young professionals that were in shortage in the target country. Canada often serves as an example of a more holistic immigration policy:

In recent years, Canada has become an even more attractive destination for immigrants after policies enacted under U.S. President Donald Trump severely restricted access to the United States. Yet, Canada is also experiencing a labor shortage exacerbated by a dearth of skilled workers. Its immigration system faces an array of other challenges as well, including a surge in asylum claims, rising deportations, and labor abuses against temporary-visa holders.

I will return to these issues often in future blogs.