My latest series of blogs has focused on long term population growth; one of the main aspects has been an attempt to understand the United Nations’ medium projection and the reasoning behind its very large margin of error (December 24, 2013 blog).

Here are the two key paragraphs that I quoted from the original report:

Future population size is sensitive to small but sustained deviations of fertility from replacement level. Thus, the low scenario results in a declining population that reaches 3.2 billion in 2150 and the high scenario leads to a growing population that rises to 24.8 billion by 2150.

The long-range projections prepared by the United Nations Population Division include several scenarios for population growth for the world and its major areas over the period 1995-2150.The medium scenario assumes that fertility in all major areas stabilizes at replacement level around 2050; the low scenario assumes that fertility is half a child lower than in the medium scenario; and the high scenario assumes that fertility is half a child higher than in the medium scenario. The constant scenario maintains fertility constant during 1995-2150 at the level estimated for 1990 – 1995, and the instant-replacement scenario makes fertility drop instantly to replacement level in 1995 and remain at that level thereafter.

Mathematically, based on achieving long-term replacement fertility rates, these projections are very easy to compute. The main question raised was how to get there. Jim Foreit in his January 14, 2014 guest blog concluded that:

A sub-replacement fertility world seems inevitable, with fewer productive adults supporting larger numbers of the elderly. What this will mean for human welfare will depend on both the future productivity of working adults and living the expected living standards for their parents.

I see an obvious conflict in the two statements and an unanswered question of how we can achieve a stable global population in the long term (which I have somewhat arbitrarily defined as 1000 years). In my last blog I explored the populations in countries that have already crossed the fertility replacement rate. For some of the reasons that I mentioned there, I couldn’t get a satisfactory answer. It seems that we need more time to observe the trends. Since it seems I cannot get answers on the ground, I will try instead to use simple mathematical models and simple examples. That’s what physicists usually do. I will start first with the math:

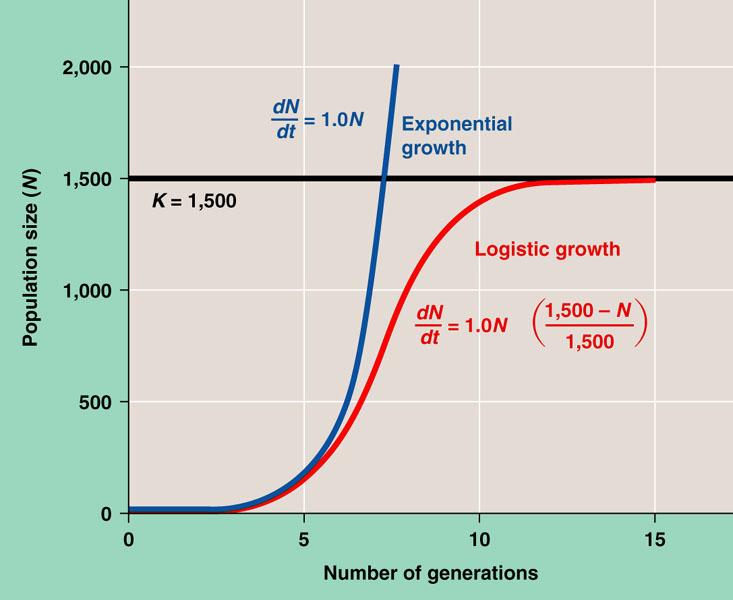

We need to explore two modes of growth: exponential growth and logistic growth. A good pictorial presentation of these two modes of growth, as related to population growth, is given in the graph below:

The term dN/dt on the left-hand side of both curves represents the rate of population growth over time; d represents change, N represents population and t represents the time. The horizontal axis represents the time in units of passing generations. The exponential growth grows unabated because the growing number of kids each have their own kids. This is represented by the fact that the growth rate is proportional to the population. The logistic curve reaches stabilization at the arbitrary population of K = 1500. The equation is identical to the exponential growth with an additional term on the right that is responsible for the saturation. This term represents negative feedback: “when the result of a process influences the operation of the process itself in such a way as to reduce changes” and the system becomes self regulating. The simplest example – and probably the most familiar – that we often use for regulating a physical system, is the thermostat. It regulates the temperature of an enclosure by measuring the actual temperature and switching on or off the heating or cooling system or regulating the flow of the heating element. I was looking for a “populationstat,” with the planet as my enclosure. The stabilization doesn’t have to be as smooth as the one showed in the logistic curve above. I can live with bumps. I can also live with reasonable limits on my ability to stabilize the system but I cannot (or we cannot) live with unbounded systems. We have found out that we know how to switch population growth off (“development is the best contraceptive” :() but I have no idea how to switch it on again. Jim Foreit says that we will have to learn how to live with this. In the next few blogs I will try to explore some alternative options.

The term dN/dt on the left-hand side of both curves represents the rate of population growth over time; d represents change, N represents population and t represents the time. The horizontal axis represents the time in units of passing generations. The exponential growth grows unabated because the growing number of kids each have their own kids. This is represented by the fact that the growth rate is proportional to the population. The logistic curve reaches stabilization at the arbitrary population of K = 1500. The equation is identical to the exponential growth with an additional term on the right that is responsible for the saturation. This term represents negative feedback: “when the result of a process influences the operation of the process itself in such a way as to reduce changes” and the system becomes self regulating. The simplest example – and probably the most familiar – that we often use for regulating a physical system, is the thermostat. It regulates the temperature of an enclosure by measuring the actual temperature and switching on or off the heating or cooling system or regulating the flow of the heating element. I was looking for a “populationstat,” with the planet as my enclosure. The stabilization doesn’t have to be as smooth as the one showed in the logistic curve above. I can live with bumps. I can also live with reasonable limits on my ability to stabilize the system but I cannot (or we cannot) live with unbounded systems. We have found out that we know how to switch population growth off (“development is the best contraceptive” :() but I have no idea how to switch it on again. Jim Foreit says that we will have to learn how to live with this. In the next few blogs I will try to explore some alternative options.

Thanks for your comment. Almost every line in your response requires a lengthy reply. The blog has bee running on a weekly basis for almost four and a half years and it will be much easier for me and for anybody else that wishes to respond, to do it via comments directed at a particular blog that addresses a particular issue.

In this spirit, let me focus on your assumption that the blog states that climate change directly relates to population. Population directly impacts climate change through an identity labeled as IPAT (Impact = Population x individual affluence x technology). Type IPAT in the search box of the site and you should be exposed to all the blogs that deal with this issue. On the time scale that I am dealing with, conversion of exponential growth to logistic growth will be required by any population-related activities. Electric cars are good for the sustainability of the planet as long as the fuel that produces the electricity is not contributing to the chemical changes in the atmosphere. Otherwise they will be part of the problem by increasing demand for dirty energy production.

Looking forward to communicating with you in various ways where we can all contribute.

Micha

Hi Micha,

I am surprised that this blog has not had more hits – it is a fascinating subject. Do you have any further thoughts on this since 2014?

One other question – I see the title contains the term ‘climate change’, so I assume you are looking at population as being driven somewhat by climate change. Personally I doubt that climate change will have much effect other than providing the need to change where we grow crops in future – so if that is required there will be many years where food supplies are reduced and the economic impact to set up new infrastructures causes hardship.

By the looks of things (Trump permitting) climate change will not be too deep – the introduction of electric motor vehicles and better control of waste gases at the power source should reduce CO2 production – I personally do not buy the IPCC version of this story and believe that a good share of climate change is due to soot from burning low grade oils. (a lot in the form of shipping at sea) rather than CO2.

However there will be many ‘populationstats’ and looking for a single one will be futile. For example, it is possible for example that our increasing microwave pollution could increase the death-rate – such a suggestion is not widely supported currently but we have only had a few years of this new pollutant.

At the other end of the equation, ‘fertility’ is probably not a serious metric – it is something that can by definition be measured fairly easily so there is a temptation to quote it – but it is really a silly value as it is so related to other real variables. This includes economic expectations, unemployment rates, the quality of healthcare, and many other real measurable variables.

I appreciate the mathematical view that you provide – it is an eye-opener for many people (and was in fact the way I found your blog).

I appreciate you taking the time and making the effort to put this together.

Thank you – David