Talking to German students in Wolmirstedt (of which Farsleben is now part) about the Holocaust

The top photograph shows students in Wolmirstedt, Germany, listening to my talk summarizing my Holocaust experiences, which peaked with my liberation by a unit of the American Army in that same town (see the May 21, 2025 blog for more details). I have been “busy” talking about the Holocaust for many years. For a glimpse of my activities, see the December 3, 2019 blog titled “Back to ‘Self-Inflicted Genocide’: Roger Hallam & the Holocaust.” Because of my academic work, in terms of global threats, I have been focused on climate change. More recently, I have expanded my scope.

In a few weeks, my wife and I will travel to Columbus, Ohio, to participate in an event associated with the last stages of the production of the film that describes the liberation and its aftermath. The making of the film was mentioned in the May 21st blog (with the error that the distribution contract was set – as of now it is still not yet set). One can find more details about this movie at https://magdeburgtrain.com/ and A Train Near Magdeburg – Columbus Association for the Performing Arts.

The film is a documentary, built around descriptions of the events Matt Rozell recorded in his book. I often wonder what will happen to this movie, and many other documentaries that are focused on the Holocaust, once my generation (I am 86; the liberation in Farsleben took place less than two weeks before my 6th birthday) is no longer around. Will discussions flourish about the facts and fictions of such movies? And what can we do now to have an impact on these discussions?

Right now, in many places in the US and other countries, teaching of the Holocaust is mandatory. The US states and countries that have such laws are shown below (through AI – Google):

US states:

As of November 2024, 29 U.S. states mandate Holocaust education in public schools. These states include: Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Maine, Michigan, Missouri, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Tennessee, Texas, and Wisconsin. The specific requirements and grade levels for instruction can vary by state.

Countries:

Many countries mandate Holocaust education in schools, including Austria, France, Germany, Hungary, Israel, the Netherlands, Poland, Switzerland, Sweden, parts of the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. In addition, the United Arab Emirates recently became the first Middle Eastern country to mandate Holocaust education in schools.

A reasoning for the mandatory teaching is provided by UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization):

Close to 80 years after the end of the Second World War, Holocaust remembrance is increasingly fragile. While surveys reveal critical knowledge gaps and indifference among younger generations, Holocaust denial and distortion thrive online and offline amidst the rise of hate speech and the proliferation of antisemitic narratives. UNESCO is working to change that as part of its International Program on Holocaust and Genocide Education (IPHGE), implemented jointly with the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum and financed by the government of Canada. The program provides training opportunities for education stakeholders in Member States, who then develop context-relevant approaches to work with local education authorities and practitioners on Holocaust education pedagogy.

Although the US Holocaust Memorial Museum was part of creating the IPHGE Holocaust remembrance initiative, President Trump recently removed the US from the international program.

Expanding the scope of teaching past events—by pairing Holocaust teaching with scientifically-deduced global threats—has a good chance of having a major impact on students and teachers in future classrooms. Such pairings might be necessary to expose future generations to existing dangers for possible mitigation. However, there are serious issues with such attempts. Last week’s blog discussed some of the prerequisites for both students and teachers. Mastery of the connected topics will necessarily limit the number of students that will choose such topics.

I wrote about my experience with such limitations when I tried to advance Environmental Studies at my school (see December 28, 2021, blog on campus politics). At my school, the number of required credits for undergraduates is 128. When discussions on multidisciplinary topics such as Environmental Studies came up, voices were raised that starting multidisciplinary topics would necessarily reduce the number of students in individual departments. Since most of campus politics runs through departments, the going gets tough.

A more serious obstacle is the prospect that the high prerequisites will keep non-college graduates out of the discussion. By their nature, future threats are highly political. Teaching early choices of future threats often amounts to choices between present and uncertain future. We see the consequences now—climate change is just being removed from the agenda of the federal government, as is academic research. Future blogs will return to these issues. One of the most productive topics of pairing Holocaust Studies with future threats is being able to recognize early signs of threats that electoral victories in democratic countries can help mitigate.

In order to immortalize the idea of “never again” for global threats, we need to expand the effort beyond the academic environment. A good starting point could be to follow the efforts of Charles Bronfman and Michael Steinhardt, who formed the “Birthright Israel” effort in cooperation with the Israeli government and other Jewish organizations (now is not a great time for a call to follow the Israeli government, but hopefully, this will change),

Taglit-Birthright Israel (Hebrew: תגלית), also known as Birthright Israel or simply Birthright, is a free ten-day heritage trip to Israel, Jerusalem, and the Golan Heights for young adults of Jewish heritage between the ages of 18 and 26. The program is sponsored by the Birthright Israel Foundation, whose donors subsidize participation.

Taglit is the Hebrew word for ‘discovery’. During their trip, participants, most of whom are visiting Israel for the first time, are encouraged to discover new meaning in their personal Jewish identity and connection to Jewish history and culture.[2]

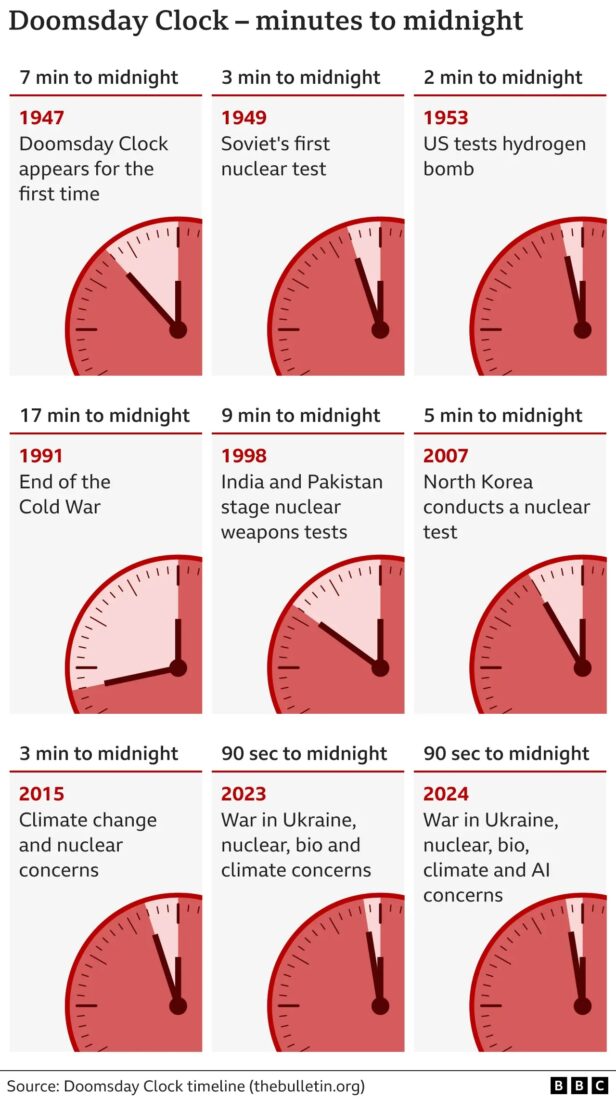

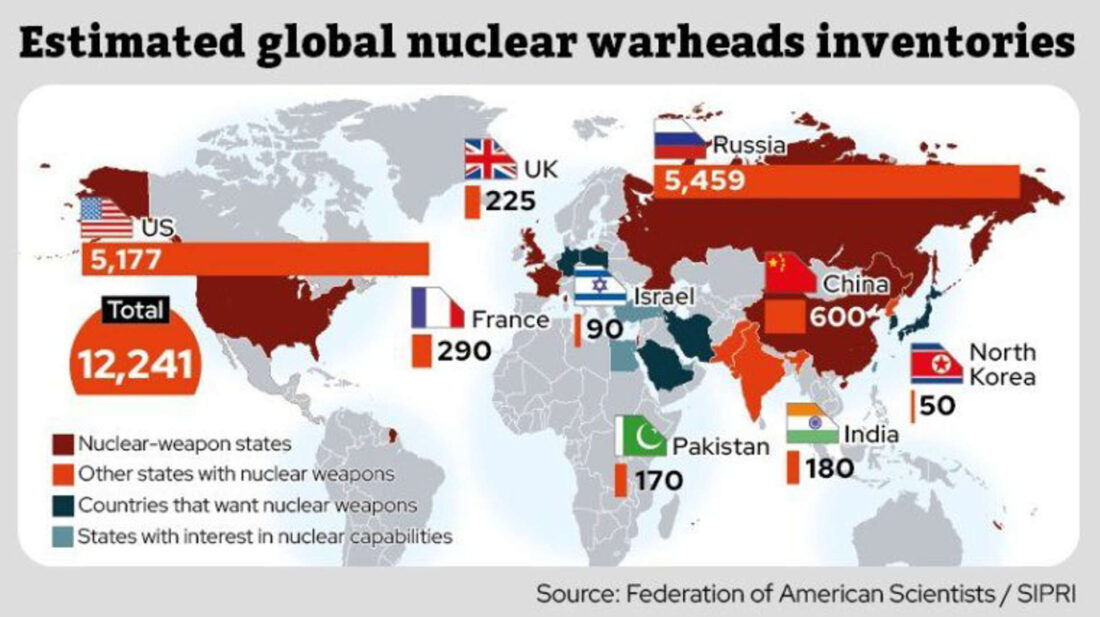

The idea here is for the Holocaust Institute to follow the Birthright effort in attracting young people in coming generations to travel to places where real early signs of future threats are being addressed. This will include future threats that may materialize, such as nuclear wars.

The Holocaust Institute’s Center for Prevention of Genocide already has an active program addressing early signs of genocide that were mentioned in last week’s blog:

The Early Warning Project—a partnership between the Simon-Skjodt Center and Dartmouth College—uses state-of-the-art research methods to identify countries at risk for mass atrocities.

Genocide and mass atrocities are not spontaneous. They are preceded by a range of early warning signs that, if detected, can give governments and institutions a chance to intervene before atrocities erupt.

The Early Warning Project produces a yearly ranked list of more than 160 countries based on their likelihood to experience a new mass killing. It also uses crowd forecasting tools to provide real-time updates, and produces in-depth reports on selected high-risk countries.

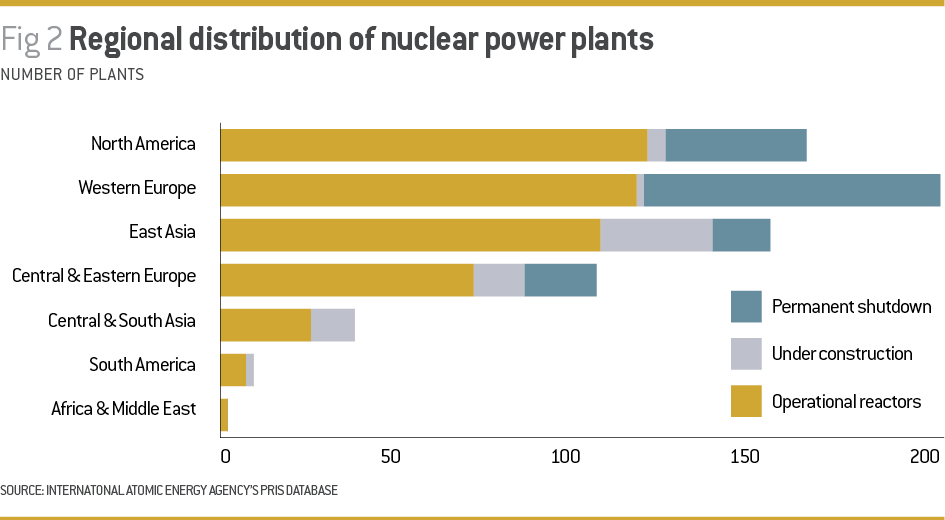

The Holocaust Institute already has a global traveling program that is targeted to donors. These programs are very expensive. The next two blogs will take a very specific step in that direction: using the US Holocaust Institute to facilitate travel to Hiroshima and/or Nagasaki (Bombed August 6th and 9th, 1945) and to either the Great Barrier Reef in Australia or the Belize Barrier Reef, examining past, future, and current destruction through two different world events (nuclear bombs and climate change-caused coral bleaching).

(Source:

(Source:

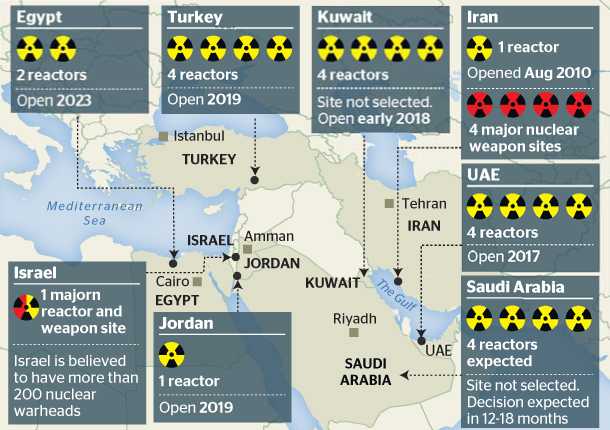

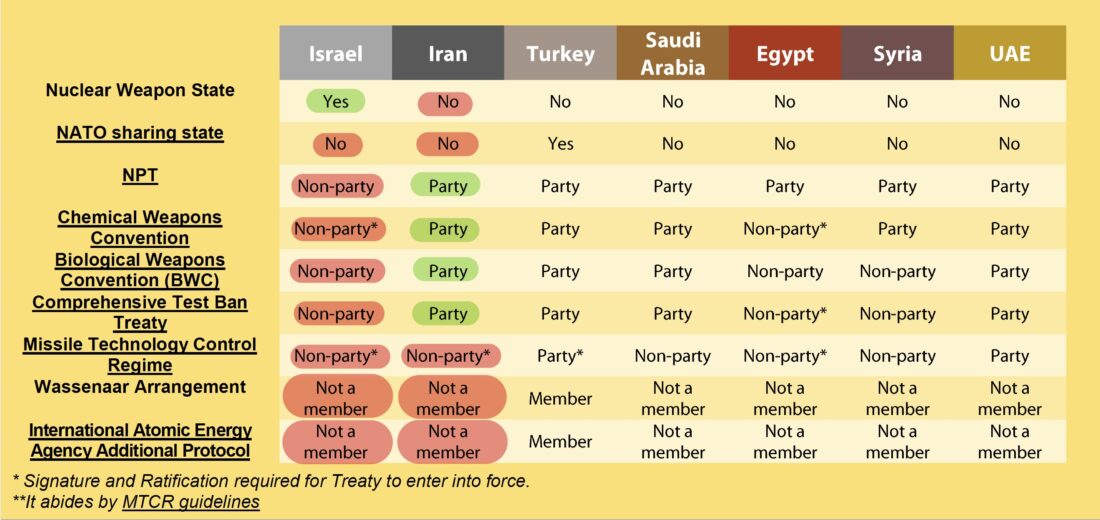

Figure 1 – Map of nuclear reactors and weapons in the Middle East (Source:

Figure 1 – Map of nuclear reactors and weapons in the Middle East (Source:

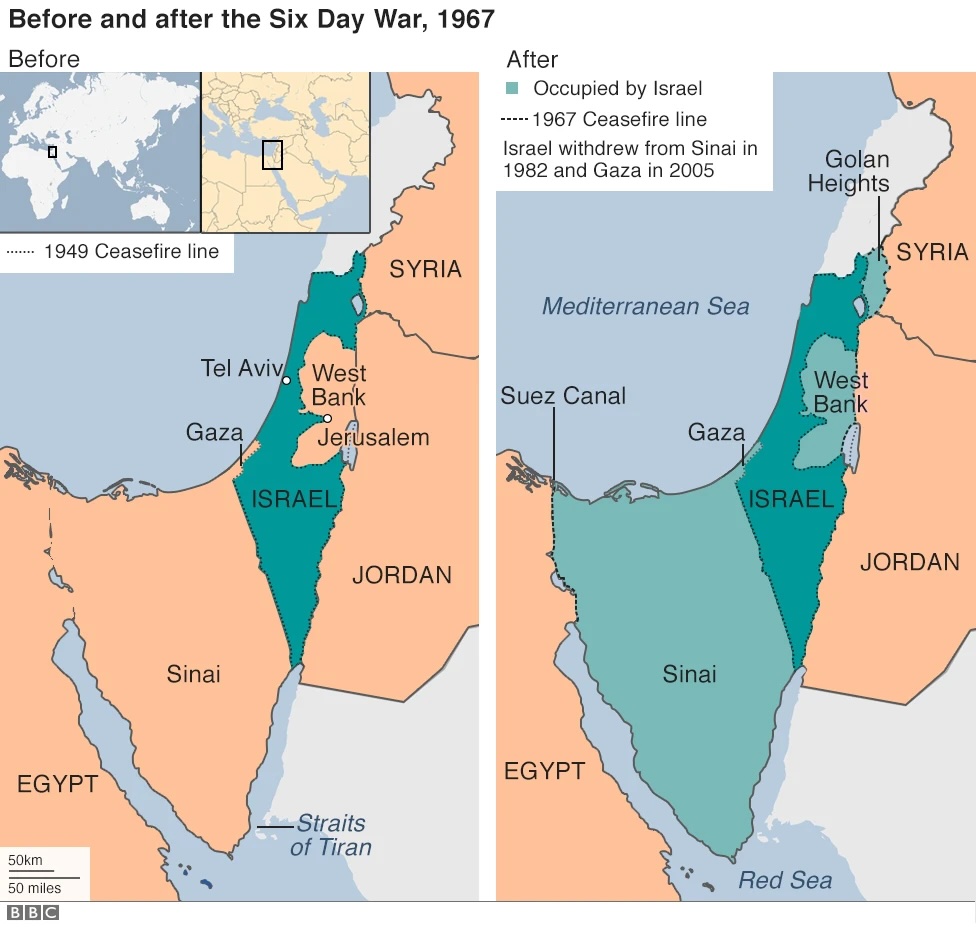

Map of the region before and after the Six-Day War (Source:

Map of the region before and after the Six-Day War (Source: