The world’s nuclear-armed states are beefing up their atomic arsenals and walking out of arms control pacts, a think tank has said. A new arms race is emerging after decades of reductions in the stockpiles since the Cold War, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI). It comes amid escalating tensions between Israel, one of the world’s nuclear powers, and Iran. Israel said it bombed Iran over the past week to stop it from being able to produce nuclear weapons. Here, The i Paper takes a look at the countries with nuclear weapons and how dangerous they are.

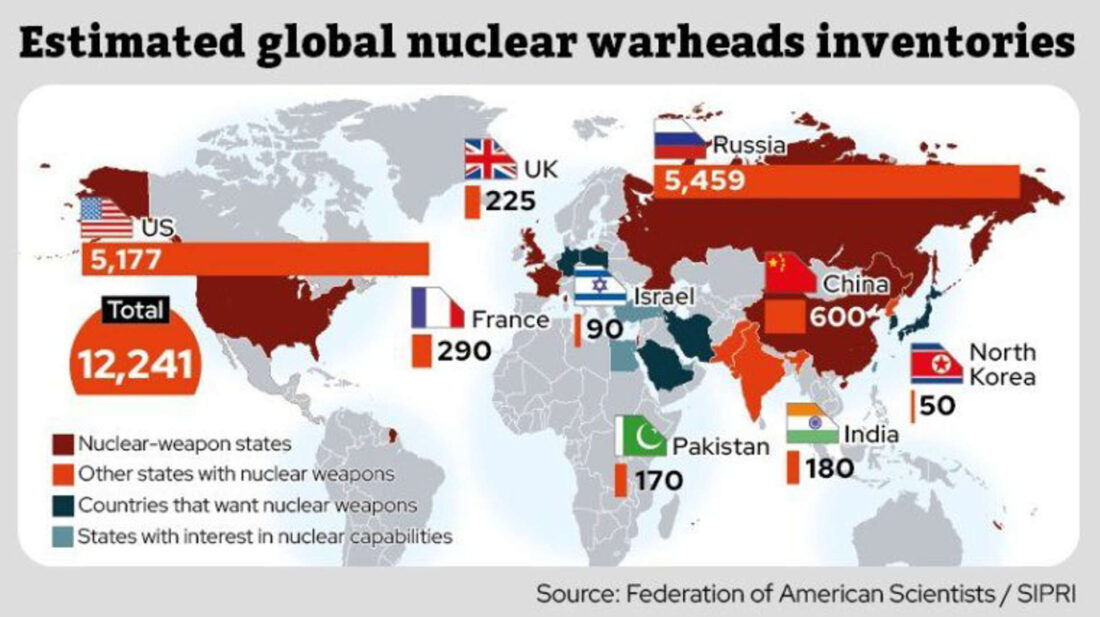

Figure 1 – Global nuclear weapons (Source: MSN)

The timing of the acquisitions:

US (1945); Soviet Union (1949); UK (1952); France (1960); China (1964); India (1974); Pakistan (1998); North Korea (2006); Israel (estimated 1960s).

One interesting insight into the Federation of American Scientists (FAS) map shown above—especially looking at the timing—is the clearly paired relationship between many of these countries. This strongly suggests that fear is a dominant motive for acquiring nuclear weapons. Fear is often a binary power. The transparent pairs are the US and Russia, the UK and France, and India and Pakistan. The seeming exception to this motivation is the pairing of UK and France; here, fear seems like less of a catalyst than leading Europe’s alliance with the US in the fight against the Soviet Union (now Russia).

Two recent blogs that were posted during or immediately after the recent “12-day war” between Iran, Israel, and the US (none of the three declared this deadly “encounter” a war), mentioned two alleged Israeli doctrines that played important roles in triggering the events. One was the Begin Doctrine (June 18, 2025 blog), which states that Israel will destroy any effort to produce nuclear weapons by a country with a declared objective to destroy it as a “Jewish State.” Meanwhile, the “Samson Option” (July 2, 2025 blog), is an alleged Israeli army doctrine that will use nuclear weapons in case all other defense options appear to fail. Neither of these two “doctrines” has ever been stated as an official policy.

The results of the “12-day war,” in terms of Iran’s ability to produce nuclear weapons, are still controversial. The latest “objective” assessment is given below:

The head of the UN’s nuclear watchdog says US strikes on Iran fell short of causing total damage to its nuclear program and that Tehran could restart enriching uranium “in a matter of months,” contradicting President Donald Trump’s claims the US set Tehran’s ambitions back by decades.

Iran’s efforts to produce nuclear weapons didn’t start with the present Ayatollah’s regime. The outline of the beginning of its efforts is summarized below by AI (through Google):

Iran’s nuclear weapons program, known as Project Amad, is believed to have begun in the late 1990s and early 2000s. This program aimed to develop and acquire weapons-grade nuclear material, test nuclear weapon components, and plan for the construction of a nuclear weapon. While Iran’s nuclear ambitions began earlier, with the establishment of a nuclear research program in the 1950s with US assistance, the transition to a weapons-focused program is what began in the late 90s/early 2000s.

As was mentioned above, it’s still too early to accurately predict the impacts of the “12-day war”—on Iran’s ability to produce nuclear weapons, nuclear spread in the Middle East, and more broadly, globally. However, it’s not too early to try to analyze the timing and pathways to nuclear weapons by the nine countries shown in the FAS figure at the top of this blog that are known to have these weapons. I followed the two smallest countries in the figure through AI (Microsoft Copilot) and imposed an analysis based on the better-known history of the other seven countries. The basic assumption here is that aside from the US Manhattan Project, which required the development of the weapon from pure scientific theory (mostly dominated by German scientists), many of the other programs were able to build somewhat on those developments—largely through espionage. From there, the methods that Israel and North Korea used were “borrowed” from the knowledge of the bigger holders. The AI summary of the nuclear developments of Israel and North Korea is summarized below:

Israel and North Korea took very different paths to nuclear capability—one shrouded in secrecy, the other marked by defiance. Here’s a breakdown of how each country acquired nuclear weapons:

Israel: The Path of Secrecy and Strategic Ambiguity

Israel has never officially confirmed possessing nuclear weapons, but it’s widely believed to maintain a substantial arsenal. Its approach is known as “nuclear opacity.”

- Origins: Israel began exploring nuclear science shortly after its founding in 1948. Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion was deeply committed to developing a deterrent, partly shaped by the trauma of the Holocaust.

- French Collaboration: In the late 1950s, France secretly helped Israel build the Dimona nuclear reactor in the Negev desert. This facility became the heart of Israel’s weapons program.

Plutonium Production: Israel is believed to have produced weapons-grade plutonium at Dimona, enabling it to build warheads without conducting public tests.

- Espionage and Covert Operations: Allegations persist that Israel may have acquired nuclear materials from abroad, including a suspected diversion of uranium from a U.S. facility in the 1960s.

- Estimated Arsenal: Experts estimate Israel has between 90 and 400 nuclear warheads, deployable via aircraft, submarines, and ballistic missiles.

- Policy: Israel has not signed the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) and maintains a doctrine of preventive strikes, as seen in its attacks on nuclear facilities in Iraq and Syria.

North Korea: The Path of Defiance and Isolation

North Korea’s nuclear journey has been marked by international confrontation and withdrawal from global treaties.

- Early Interest: North Korea began pursuing nuclear technology in the 1950s, initially with Soviet assistance for peaceful purposes.

- Yongbyon Complex: By the 1980s, North Korea had developed the Yongbyon nuclear facility, which became central to its weapons program.

- Withdrawal from NPT: In 2003, North Korea became the first country to withdraw from the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, citing U.S. threats.

- Nuclear Tests: It conducted its first nuclear test in 2006, followed by five more, including a thermonuclear test in 2017.

Fissile Material: North Korea produces plutonium and highly enriched uranium, with enough material for up to 90 warheads, though it’s believed to have assembled around 50.

-

-

-

-

- Delivery Systems: It has developed a range of ballistic missiles, including intercontinental missiles capable of reaching the U.S..

- Current Status: Kim Jong Un continues to expand the arsenal, with new enrichment facilities and missile tests defying UN sanctions.

-

-

-

The five references that were used by the AI to produce this summary are given below:

Nuclear weapons and Israel – Wikipedia

Fact Sheet: Israel’s Nuclear Inventory – Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation

North Korea and weapons of mass destruction – Wikipedia

North Korea’s Nuclear Weapons and Missile Programs – Congressional Research Service

Kim Jong Un Quietly Advances North Korea’s Nuclear Program – Newsweek

Five of the nine countries shown in Figure 1 possess veto powers in the decisions of the security council that guarantee their central role in world affairs. This was not always the case:

On October 25, 1971, the UN General Assembly passed United Nations Resolution 2758 (XXVI) which stated that the People’s Republic of China is the only legitimate government of China. The resolution replaced the ROC with the PRC as a permanent member of the Security Council in the United Nations.

ROC refers to the Republic of China, the official name of Taiwan, and PRC refers to the People’s Republic of China, or China “proper,” which until recently (2023) had the largest global population.

As can be seen in the timing above, the UN resolution to replace ROC with PRC in the UN security council came well after 1949, the year that the PRC won control of the Chinese government. The resolution came after China acquired atomic weapons in 1964. China had some problems in the 1960s but they were mostly internal. Nuclear weapons couldn’t solve any of them. China wanted international respect and power. With the 1971 UN resolution, they got both.

Anybody who saw the recent movie “Oppenheimer” learned important aspects of the history of nuclear weapons. The development of the first atomic bomb, and its only deadly use in war setting, took place by the US during WWII via the Manhattan Project. The direct motivation was fear that Germany was already pursuing such development.

Important aspects of that fear are summarized by AI (through Google):

The fear that Nazi Germany was actively pursuing an atomic bomb was a primary motivator for the Manhattan Project. Fueled by reports of German nuclear research and the escape of scientists from Europe, including Albert Einstein, who warned President Roosevelt, the US initiated the top-secret project to develop nuclear weapons before Germany could. This fear, coupled with the potential for such a devastating weapon, drove the unprecedented mobilization of scientific and industrial resources.

- German Nuclear Research:

In 1938, German scientists Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassmann discovered nuclear fission, the process that could potentially be used to create an atomic bomb. This discovery, along with reports of ongoing German research, raised serious concerns in the United States.

- Einstein’s Warning:

In 1939, Albert Einstein, along with Leo Szilard, wrote a letter to President Roosevelt, urging him to take action and begin research into nuclear weapons before Germany could.

The aftermath of WWII put the power of the US and its allies (the West) in direct competition with the Soviet Union and its allies (the East). The rest of the world was still far behind. Once the US demonstrated the impact of the nuclear bomb with the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945, fear took over and the Soviet Union mobilized all its resources (mainly spying) to master the technology. They were able to explode the first one in 1949. The Soviet Union became Russia in the 1990s. As the figure shows, the US and Russia keep the balance of fear between them. Western Europe still largely relies on the US nuclear umbrella to protect them from Russia. However, since many Europeans did participate in the Manhattan project, UK and France decided to develop their own capabilities. They needed more power to keep the balance with the US.

Meanwhile, once China developed its nuclear weapons and got the power and respect that those confer, India followed suit:

India’s loss to China in a brief Himalayan border war in October 1962, provided the New Delhi government impetus for developing nuclear weapons as a means of deterring potential Chinese aggression.[32] By 1964 India was in a position to develop nuclear weapons.[33] Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri opposed developing nuclear weapons but fell under intense political pressure, including elements within the ruling Indian National Congress. India was also unable to obtain security guarantees from either the United States or the Soviet Union. As a result, Shastri announced that India would pursue the capability of what it called “peaceful nuclear explosions” that could be weaponized in the future.[26]

Three years before the first test of India’s nuclear bomb, East Pakistan split from West Pakistan to form the independent country of Bangladesh. India played a key role in the process. Below is a short AI (through Google) summary of the Indian involvement in the Bangladesh Liberation War:

India played a crucial role in the Bangladesh Liberation War of 1971, providing military, diplomatic, and humanitarian support to the Bangladeshi independence movement. This support ultimately led to the defeat of Pakistan and the creation of Bangladesh.

The tension between India and Pakistan continues, mainly focusing on the divided area of Kashmir and the treatment of the large Muslim minority in India (approaching 200 million or about 15% of the population). It took some time, but in 1998 Pakistan announced its own nuclear weapons, becoming the only Muslim-governed country shown in the figure to have such capability. Fear was the main motive. In the recent “12-day war,” Iranian voices could be heard saying that if Israel were to use nuclear weapons against Iran, Pakistan would retaliate. Almost at the same time as this announcement took place, Pakistan recommended that President Trump be this year’s recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize.

The last two countries that are shown in the figure to posses nuclear weapons are Israel and North Korea. What distinguishes them from the rest of the possessors is that while their fear was existential, it came from overwhelming hostile conventional powers rather than nuclear power. Next week’s blog will focus on their road to nuclear weapons and the extension of the “holders” map to “thresholders” map (see last week’s blog) that includes Iran.

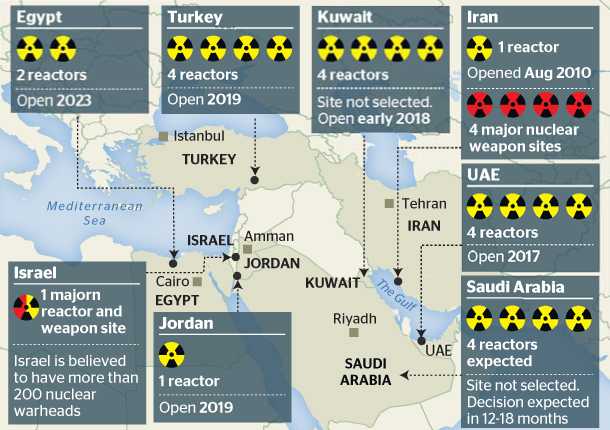

Figure 1 – Map of nuclear reactors and weapons in the Middle East (Source:

Figure 1 – Map of nuclear reactors and weapons in the Middle East (Source:

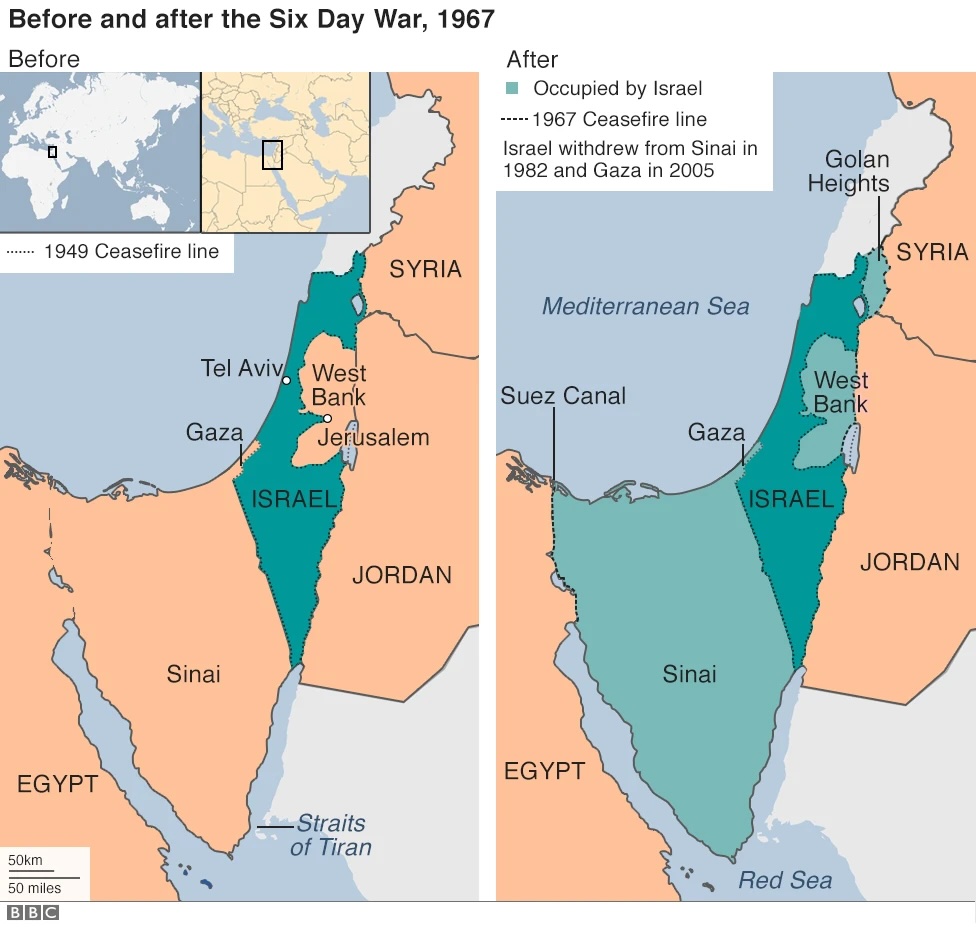

Map of the region before and after the Six-Day War (Source:

Map of the region before and after the Six-Day War (Source:

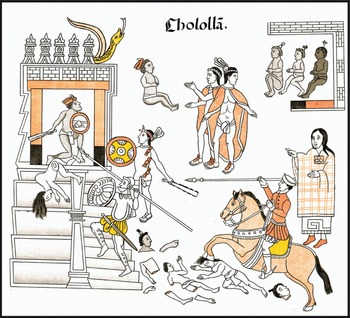

Figure 1 – Genocidal massacres in the Spanish conquest of the Americas (Source:

Figure 1 – Genocidal massacres in the Spanish conquest of the Americas (Source: