Four days ago, the NYT featured Paul Krugman’s op-ed, “Australia Shows Us the Road to Hell,” where he described the urgent situation of the fires now engulfing the entire continent and hypothesized about strategies for confronting the political issues blocking relevant policy changes:

What might an effective political strategy look like? I’ve been rereading a 2014 speech by the eminent political scientist Robert Keohane, who suggested that one way to get past the political impasse on climate might be via “an emphasis on huge infrastructural projects that created jobs” — in other words, a Green New Deal. Such a strategy could give birth to a “large climate-industrial complex,” which would actually be a good thing in terms of political sustainability.

Can such a strategy succeed? I don’t know. But it looks like our only chance given the political reality in Australia, America, and elsewhere — namely, that powerful forces on the right are determined to keep us barreling down the road to hell.

On the front page of the same issue of the NYT, Lisa Friedman wrote, “Trump’s Move Against Landmark Environmental Law Caps a Relentless Agenda”:

WASHINGTON — President Trump on Thursday capped a three-year drive to roll back clean air and water protections by proposing stark changes to the nation’s oldest and most established environmental law that could exempt major infrastructure projects from environmental review.

Paul Krugman warned of political forces on the right and the damage they were doing/could do but even he probably didn’t see that coming.

Depending on the election outcome, it will be either next year or 2025 before we can expect the federal government to be of any help with the issue. In fact, at least for now, the federal government will likely do everything in its power to accelerate the damage that climate is inflicting on the US and the world.

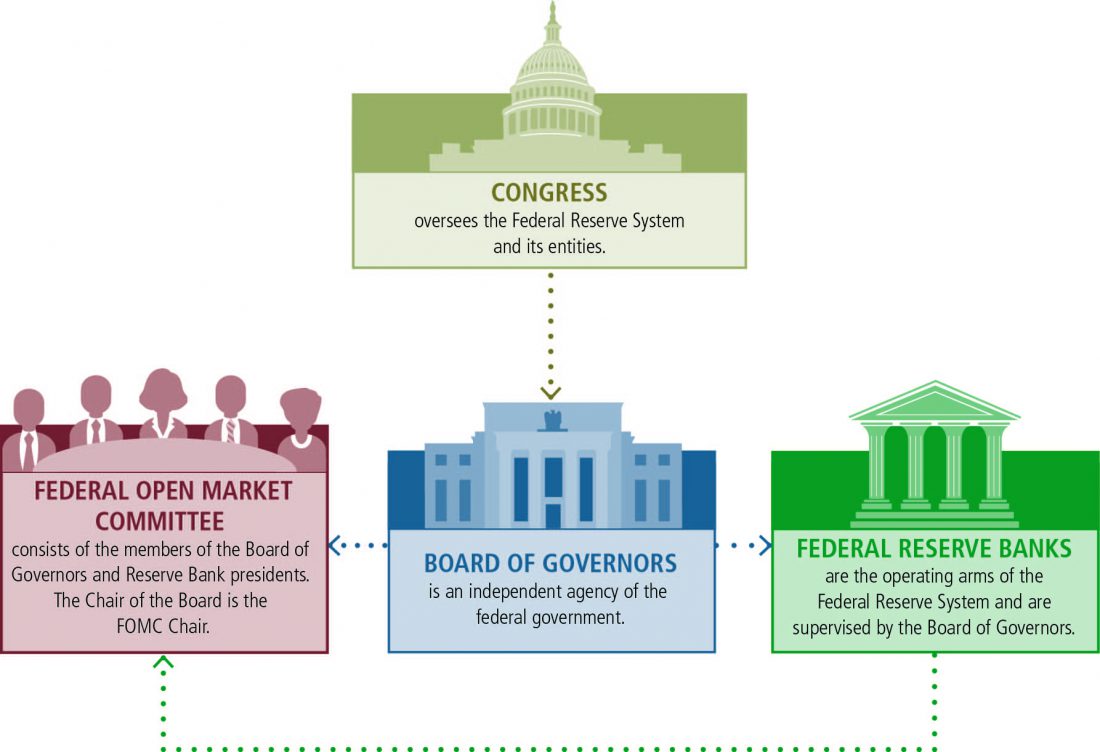

Fortunately, the federal government is not the only one in charge of the money. The Federal Reserve System (also known as the Fed) is the US’ central banking system. It is under Congress—and the Board of Governors that runs it must report to that body—but it is, “an independent agency that makes decisions based on the best available evidence and analysis, without taking politics into consideration.”

In addition, though the Congress sets the goals for monetary policy, decisions of the Board—and the Fed’s monetary policy-setting body, the Federal Open Market Committee—about how to reach those goals do not require approval by the President or anyone else in the executive or legislative branches of government.

The Fed has a large impact on the economy—among other powers, it sets the interest rates and thus directly influences key activities. These include housing (through mortgage rates) and the value of the US currency relative to other major currencies, which impacts both trade and the money available for major infrastructure projects.

I’m glad to see that it looks like several of the 12 districts of the Reserve Banks that make up the Federal Reserve are taking the impact of climate change much more seriously than the federal government as a whole.

I’m glad to see that it looks like several of the 12 districts of the Reserve Banks that make up the Federal Reserve are taking the impact of climate change much more seriously than the federal government as a whole.

I had never heard of the American real estate blog Curbed before now but I will be rectifying that oversight. One of its articles from October focused my attention on the San Francisco Federal Reserve and how its publication is giving special attention to the present impacts of climate change, “How climate change creates a ‘new abnormal’ for the real estate market”:

A report from the San Francisco Federal Reserve underscores how climate shifts create big investment and economic risks

The publication page for the San Francisco Federal Reserve, part of the nation’s central banking system, isn’t known for light reading. Recent research papers, such as “Yield Curve Responses to Introducing Negative Policy Rates” or “Precautionary Pricing: The Disinflationary Effects of ELB Risk,” aren’t exactly meant to go viral.

But a new set of papers around climate change should gain an audience beyond academic and economic circles. Titled “Strategies to Address Climate Change Risk in Low- and Moderate-income Communities,” this collection of 18 articles by academics and experts collectively offers “one of the most specific and dire accountings of the dangers posed to businesses and communities in the United States,” according to the New York Times.

Other central banks and bankers are taking notice of climate change as well; Since 2017, 46 central banks and regulators have joined the Network for Greening the Financial System, according to the Financial Times, including representatives from China, France, and the United Kingdom. The World Economic Forum’s 2019 Global Risk Report listed three risks of climate change—extreme weather events, failure of climate change mitigation and adaptation, and natural disasters—as both the most immediate and most damaging.

These risks will also affect real estate investments and the operations of the real estate industry, which, despite increasingly grave reports about the impact of climate change on land use and sea levels, has not taken the policy steps and process reviews necessary to deal with the coming challenges.

The special San Francisco Federal Reserve issue of the Community Development Innovation Review addresses how climate change is already impacting the real estate market and offers some detailed advice on how we can adapt:

Without smart, proactive investments in adaptive capacity and resilience, low- and moderate-income (LMI) communities will likely be disproportionately affected by climate change-related events.1 This issue of the Community Development Innovation Review explores these investment opportunities and calls on the community development sector to take a leadership role in preparing vulnerable regions most at risk for a “new abnormal.”2

This issue would not have been possible without the extraordinary work of its guest editor, Jesse M. Keenan. A leading thinker on climate change risk—even adding the helpful term “climate gentrification” to the lexicon—Jesse recruited a remarkable group of thirty-eight authors to write for this issue. Their contributions, and Jesse’s, advance the community development sector and help us better prepare for a changing world.

Despite the challenges that lie ahead, I’m encouraged by the work that’s already begun. As recently as this summer, in fact, the Low Income Investment Fund—a national Community Development Financial Institution—issued a $100 million “Sustainability Bond,” the first public offering directly aligned with the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals.3 If that’s any indication, the community development sector has already begun to mobilize capital to address the impacts of climate change in LMI communities.

Nor is the San Francisco Federal Reserve alone. The Dallas Federal Reserve echoed the sentiment:

CORPUS CHRISTI, Texas/ WASHINGTON (Reuters) – Dallas Federal Reserve President Robert Kaplan faced more questions on one particular topic than any other at a recent lunch with local business owners and community leaders on Texas’s Gulf Coast.

Texas has suffered catastrophic floods and billions in related losses in recent years. Now, “it’s hard to meet with a business person or a city or a community leader in this state” who doesn’t have questions on climate change, Kaplan, a former Goldman Sachs investment banker and one of 17 Fed policymakers, said in response to a question at the Sept. 20 lunch.

It’s not just Texas. After devastating fires in Northern California and corrosive storms on the Carolina and Florida coasts, the Fed’s regional banks are delving deeper into how the earth’s warming will impact U.S. businesses, consumers and the country’s $17 trillion asset banking system.

I will keep looking at the economic and social impacts that climate change is fueling on the real estate market, mortgage rate, insurance market, immigration, and the US army.

Stay tuned.

Blackrock boss Larry Fink offered this to his clients ($7 trillion under management):

//The evidence on climate risk is compelling investors to reassess core assumptions about modern finance,” he wrote, explaining that climate change is the top concern that investors raise with BlackRock. “In the near future — and sooner than most anticipate — there will be a significant reallocation of capital.”//

https://www.blackrock.com/corporate/investor-relations/larry-fink-ceo-letter

Moody’s Investor Service (via a subsidiary 427):

//”As the effects of climate change increasingly threat- en financial stability, investors and regulators are seeking to understand what impacts lie ahead, and calling for an increase in physical climate risk assess- ment and disclosure in line with the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD).1 It is important to quantify risks under different climate scenarios to assess the scale of financial risk posed by physical climate change.”//

http://427mt.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Demystifying-Scenario-Analysis_427_2019.pdf

The New York Fed has been busily bailing out the banks (and their clients at a remove) since September, more support for the status quo. All of these enterprises are behind the curve, whether it’s possible for them or anyone else to catch up with a rapidly deteriorating present is anyone’s guess.