2015 is knocking at the door. I just got The Economist’s “The World in 2015” special issue both in print and digital form. It’s full of numbers, predictions and stories. Most of its numbers and predictions are optimistic extrapolations of the present. The majority of the Science and Technology section includes information that is on the brink of public announcement. There also is a section by a science-fiction writer (Alastair Reynolds) that discusses which elements of fiction might soon become fact. The piece includes flying cars, talking to robots, new stuff from the Large Hadron Collider, etc., but it makes no predictions about what will happen to the planet as a whole. After all, there is no profit in trying to upset readers.

I will try to welcome 2015 a bit differently. On November 11th, the US and Chinese presidents came to a landmark agreement: the US will accelerate the speed of its current reduction of greenhouse gas emissions so that its level by 2025 will be close to 30% below its level in 2005 (double the pace of reduction it targeted for the period from 2005 to 2020). Meanwhile, China’s emissions will peak by 2030 – by which time sustainable sources should constitute at least 20% of its energy supply. People around the world saw this agreement by the two worst polluting countries as a good framework upon which to base a global agreement – one which will be discussed at the United Nations Climate Change Conference scheduled be held in Paris, France in December of 2015. Many eyes are now turning to India to see if it will follow. I will try to follow the global preparations for the December 2015 Paris meeting and include updates in this blog.

One of my main recurring themes on Climate Change Fork has been trying to follow the global energy transition from fossil fuels to a more sustainable mix. That mix must necessarily avoid changing the chemistry of the atmosphere, since any modification to the planetary energy balance could drastically affect the global climate. I have just ended a series of blogs (see all four November blogs) trying to make the case that such a transition is indeed possible, despite the many voices that disagree. Up to now I have discussed energy transition as a global phenomenon (see December 24, 2012 blog) with anecdotal references to individual countries. I think that it’s high time to change gear and address a few individual countries’ efforts in some more depth, as well as better defining the stuttering process that attempts at such transition entail. I have chosen six countries to follow, with the hope that their experiences can teach us all. These countries are China, US, India, Australia, France and Denmark. I have rearranged my computer’s filing system that is set to mimic my book’s chapter with updated information, to reflect on what takes place in these countries, in addition to (not instead of) the global picture. I plan to sustain my focus on the energy transitions that take place within these countries – at least until the Paris conference. That said, I fully expect that this focus will be interrupted frequently to reflect on important current events that I will wish to comment on.

I’ll start here with Germany and an article written by Justin Gillis in The New York Times. The article is focused on Germany’s energy transition and some of the important issues that it is raising. Below are some of the key paragraphs:

A reckoning is at hand, and nowhere is that clearer than in Germany. Even as the country sets records nearly every month for renewable power production, the changes have devastated its utility companies, whose profits from power generation have collapsed.

… Taking full advantage of the possibilities may require scrapping the old rules of electricity markets and starting over, industry observers say — perhaps with techniques like paying utilities extra to keep conventional power plants on standby for times when the wind is not blowing and the sun is not shining. The German government has acknowledged the need for new rules, though it has yet to figure out what they should be. A handful of American states are beginning a similar reconsideration of how their electric systems operate.

‘It’s pretty amazing what’s happening, really,’ said Gerard Reid, an Irish financier working in Berlin on German energy projects. ‘The Germans call it a transformation, but to me it’s a revolution.’

… The shifting economics can largely be traced to China, by way of Germany. Over the past decade, the Germans set out to lower the cost of going green by creating rapid growth in the once-tiny market for renewable power.

Germany has spent more than $140 billion on its program, dangling guaranteed returns for farmers, homeowners, businesses and local cooperatives willing to install solar panels, wind turbines, biogas plants and other sources of renewable energy. The plan is paid for through surcharges on electricity bills that cost the typical German family roughly $280 a year, though some of that has been offset as renewables have pushed down wholesale electricity prices.

… In Germany, where solar panels supply 7 percent of power and wind turbines about 10 percent, wholesale power prices have crashed during what were once the most profitable times of day. ‘We were late entering into the renewables market — possibly too late,’ Peter Terium, chief executive of the giant utility RWE, admitted this spring as he announced a $3.8 billion annual loss.

The big German utilities are warning — or pleading, perhaps — that the revolution cannot be allowed to go forward without them. And outside experts say they may have a point.

The Achilles’ heel of renewable power is that it is intermittent, so German utilities have had to dial their conventional power plants up and down rapidly to compensate. The plants are not necessarily profitable when operated this way, and the utilities have been threatening to shut down facilities that some analysts say the country needs as backup.

The situation is further complicated by the government’s determination to get rid of Germany’s nuclear power stations over the next decade, the culmination of a long battle that reached its peak after the 2011 Fukushima disaster in Japan. As that plan unfolds, shutting down a source of low-emission power, Germany’s notable success in cutting greenhouse gases has stalled.

So, what is happening in Germany? The German program for energy transition is summarized in a document titled “Energy Transition – the German Energiewende.”

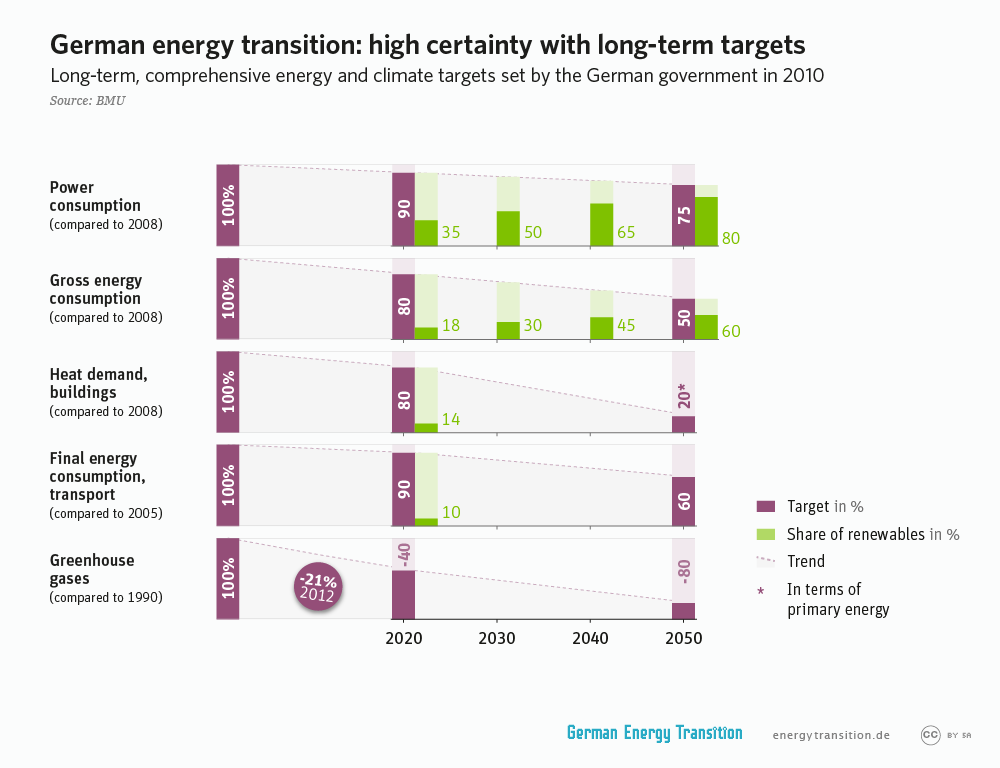

The government-approved program objectives were set in 2010 and are summarized in figure 1. As the site mentions, the history of the program didn’t start with the present government or with the realization that an energy transition is needed to mitigate anthropogenic climate change. Instead, it started as an anti-nuclear effort, and has developed and gained public support throughout the years.

Figure 1 – Government Approved Objectives of the German Energy Transition

According to German sources, the program enjoys wide public support (60%) but since there are winners and losers in the program, there is no shortage of public disagreements.

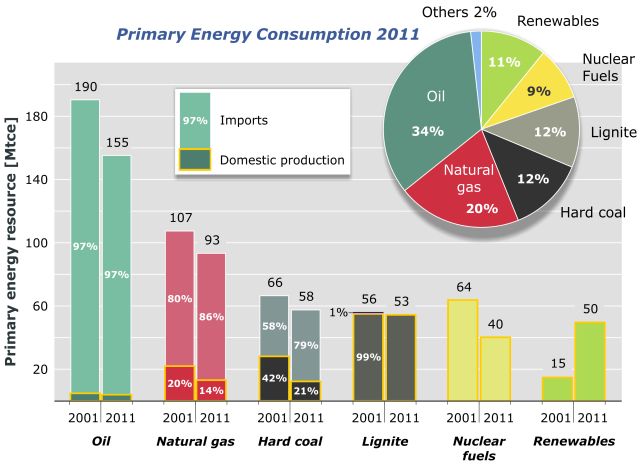

The distribution of primary energy resources, as of shortly after the adoption of the program, is summarized in figure 2.

Figure 2 – Primary Energy Consumption in Germany – 2011

The program is evolving. As Justin Gillis mentioned in his article, the Fukushima nuclear disaster in Japan has left a serious mark on Germany’s policy makers. Shortly after the disaster, on May 29, 2011, Merkel’s government announced that it would close all of its nuclear power plants by 2022. Eight of the seventeen operating reactors in Germany were permanently shut down following Fukushima. Energy supply had to adjust, and coal and other fossil fuels have filled much of the gap.

On December 4th, the government announced the following adjustment:

BERLIN — Germany has fallen behind in its ambitious goals for reducing carbon emissions. It is burning more coal than at any point since 1990. And German companies are complaining that the nation’s energy policies are hurting their ability to compete globally.

But on Wednesday, Chancellor Angela Merkel’s government said it was redoubling its efforts, proposing new measures to help it reach the emissions-reduction target for 2020 it set seven years ago when it undertook an aggressive effort to combat climate change.

However, something else happened the same day, as reported in a piece by Paul Hockenos that appeared on “Renewable Energy World”:

BERLIN — Germany’s biggest utility E.ON — long a pillar of the country’s fossil fuel and nuclear industry — dropped a bombshell on Europe’s business world with the announcement that the multinational was exiting the conventional energy market in favor of a new business model based on renewables, intelligent grid systems, energy management and other services. Indeed, the company seems finally to have drawn the logical consequences from the Energiewende, Germany’s renewable energy transition, after years of resisting the ambitious transformation of the nation’s energy supply.

‘This is part of a transformation that almost all of Europe’s major utilities are currently undergoing in response to fundamental changes in their energy markets,’ says Toby Couture, director of the Berlin-based consulting firm E3 Analytics. ‘They’re endorsing different adaption strategies. E.ON’s seems to be the boldest, the most far-reaching so far.’

A few days later, an article in The Economist provided some more details:

FOR many Germans, E.ON, the country’s biggest utility, is a symbol of stability. But on November 30th it surprised by announcing it would split itself up. In 2016 it will float a new company which will include its power generation from nuclear and fossil fuels, as well as fossil-fuel exploration and production. The rump—which will keep the E.ON brand—will make money from renewable energy, distribution and ‘customer solutions’, a grab-bag of offerings such as advice, smart-metering and the like. The firm’s boss, Johannes Teyssen, said that as a sprawling integrated utility E.ON could only be ‘mediocre’. Two focused ones would do a much better job.

As Justin Gillis’ piece made clear, the majority of German utilities fought tooth and nail against the new program. In the next blogs I will try to explore the reasons for their opposition and the role of the intermittent nature of sustainable sources in the energy transition. Meanwhile, it is interesting to see that Germany’s largest utility is sort of switching sides by splitting not only its focus but also its entire organization.

Pingback: India – the Global Lighthouse | ClimateChangeFork