Last week, I reintroduced the concept of the social cost of carbon and explored a recent University of Chicago working paper (WP). The WP delved into President Biden’s attempts to reframe the conversation about the economic impact of climate change, steering away from the Trump administration’s assessments and policies. Back in 2019, in a blog called, “Pay Now or Pay Later” (December 17, 2019), I looked at a set of economic projections during President Trump’s tenure.

Last week’s post presented a graphic comparison of the social cost of carbon between President Trump’s administration’s calculations and those of the WP. I also included the graphic that laid out the WP’s major recommendations. In addition, I posted the abstract from the WP that summarized the two most critical recommended actions: changing the discount rate back to 2% (from as high as 7%) and updating the previous social cost of carbon calculations.

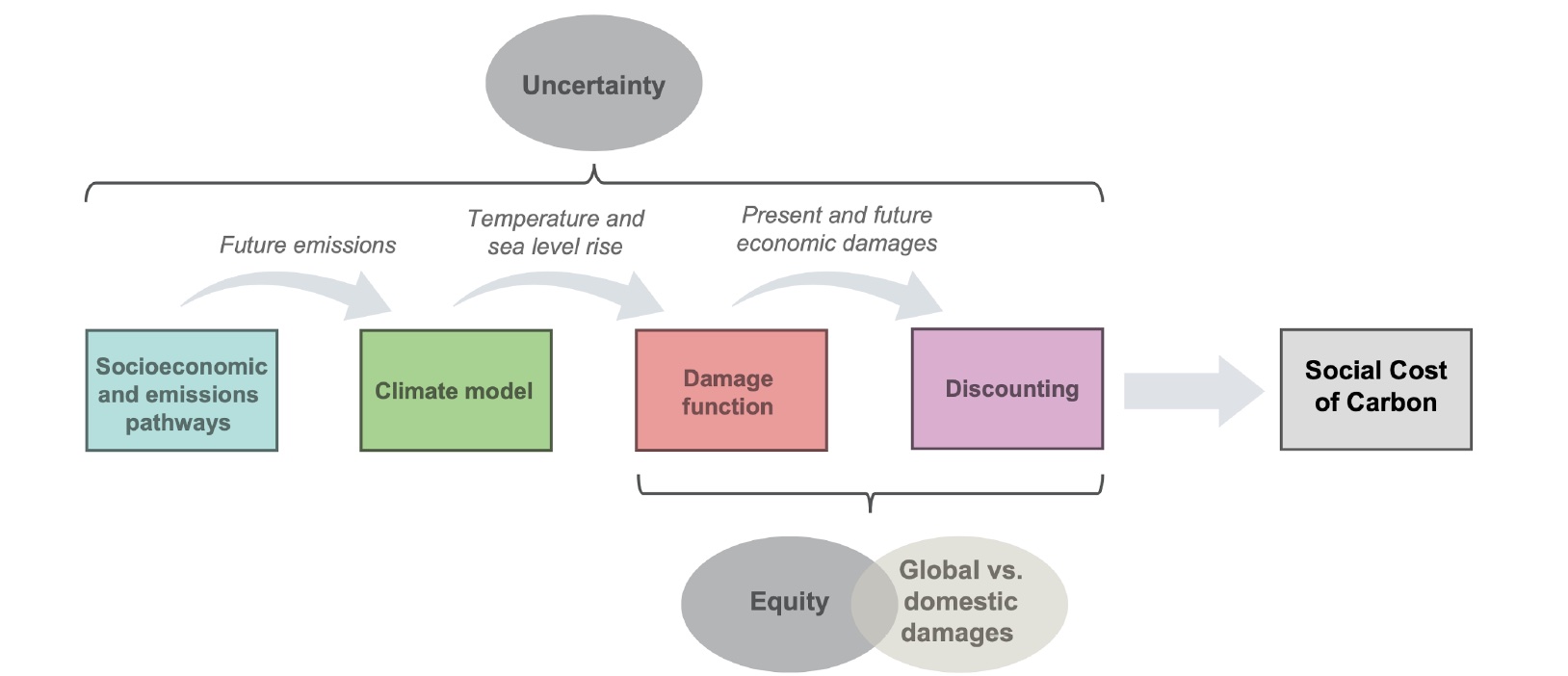

The figure below gives a general outline of the updated social cost of carbon. The WP provides details and supporting literature for each element of the calculation.

Seven ingredients for calculating the Social Cost of Carbon. This figure displays the four “modules” that compose the SCC (colored boxes), and the three key modeling decisions (grey ovals) that together form the seven “ingredients” necessary to compute an SCC.

Unsurprisingly, the change in the discount rate, the last element of the calculation, makes up a significant portion of the document. I have emphasized some of the points I find most relevant:

The final step in the SCC calculation is to express this stream of damages as a single present value, so that future costs and benefits can be directly compared to costs and benefits of actions taken today. Discounting is the process by which each year’s future values are reduced to enable comparison with current costs or benefits to society. The “discount rate” determines the magnitude of this reduction. Because CO2 emissions persist in the atmosphere and lead to long-lasting climatological shifts, small differences in the choice of discount rate can compound over time and lead to meaningful differences in the SCC. There are two reasons for “discounting the future,” or more precisely for discounting future monetary amounts, whether benefits or costs. The first is that an additional dollar is worth more to a poor person than a wealthy one, which is referred to in technical terms as the declining marginal value of consumption. The relevance for the SCC is that damages from climate change that occur in the future will matter less to society than those that occur today, because societies will be wealthier. The second, which is debated more vigorously, is the pure rate of time preference: people value the future less than the present, regardless of income levels. While individuals may undervalue the future because of the possibility that they will no longer be alive, it is unclear how to apply such logic to society as a whole facing centuries of climate change. Perhaps the most compelling explanation for a nonzero pure rate of time preference is the possibility of a disaster (e.g., asteroids or nuclear war) that wipes out the population at some point in the future, thus removing the value of any events that happen afterwards. The government regularly has to make judgments about the discount rate when trading off the costs and benefits of a regulation or project that will endure for multiple years. In general, U.S. government agencies have relied on the Office of Management and Budget’s (OMB’s) guidance to federal agencies on the development of regulatory analysis in Circular A-4, and used 3 percent and 7 percent discount rates in cost-benefit analysis. 61 These two values are justified based on observed market rates of return, which can be used to infer the discount rate for the SCC since any expenditures incurred today to mitigate CO2 emissions must be financed just like any other investment. The 3 percent discount rate is a proxy for the real, after-tax riskless interest rate associated with U.S. government bonds and the 7 percent rate is intended to reflect real equity returns like those in the stock market. However, climate change involves intergenerational tradeoffs, raising difficult scientific, philosophical and legal questions regarding equity across long periods of time. There is no scientific consensus about the correct approach to discounting for the SCC.

The social cost of carbon is explicitly meant to account for future costs but meanwhile, we are seeing significant economic impacts of climate change right now:

Extreme Weather

“U.S. Disaster Costs Doubled in 2020, Reflecting Costs of Climate Change”

Hurricanes, wildfires and other disasters across the United States caused $95 billion in damage last year, according to new data, almost double the amount in 2019 and the third-highest losses since 2010.

Supply-Chain Disruptions

“Climate change will disrupt supply chains much more than Covid — here’s how businesses can prepare”

The onset of the coronavirus pandemic caused unprecedented, worldwide supply-chain disruptions, but experts say that’s a drop in the bucket compared with the disruptions that climate change will cause.

Wildfires in the American West, flooding in China and Europe and drought in South America are already disrupting supplies of everything from lumber to chocolate to sushi rice.

Insurance

“Climate Threats Could Mean Big Jumps in Insurance Costs This Year”

The National Flood Insurance Program, which provides the vast majority of United States flood insurance policies, would have to quadruple premiums on high-risk homes inside floodplains to reflect the risks they already face, according to data issued on Monday by the First Street Foundation, a group of academics and experts that models flood risks.

By 2050, First Street projected, increased flooding tied to climate change will require a sevenfold increase.

“Climate Change Could Cut World Economy by $23 Trillion in 2050, Insurance Giant Warns”

Rising temperatures are likely to reduce global wealth significantly by 2050, as crop yields fall, disease spreads and rising seas consume coastal cities, a major insurance company warned Thursday, highlighting the consequences if the world fails to quickly slow the use of fossil fuels.

The effects of climate change can be expected to shave 11 percent to 14 percent off global economic output by 2050 compared with growth levels without climate change, according to a report from Swiss Re, one of the world’s largest providers of insurance to other insurance companies. That amounts to as much as $23 trillion in reduced annual global economic output worldwide as a result of climate change.

Pay Now or Pay Later

“Tiny Town, Big Decision: What Are We Willing to Pay to Fight the Rising Sea?”

On the Outer Banks, homeowners in Avon are confronting a tax increase of almost 50 percent to protect their homes, the only road into town, and perhaps the community’s very existence.

“Why Climate Change is a Risk to Financial Markets”

LONDON — Climate change is increasingly influencing investment decisions, but it also poses certain risks to financial stability that are not being taken completely seriously, experts have told CNBC.

… There are two main ways in how climate change is a problem from a financial point of view: Its physical effects, such as extreme weather events; and the impact of moving to a less carbon dependent economy.

“When a country is hit by a natural disaster — and these disasters are becoming more frequent and more severe — then property is affected, production capacity of agriculture, of industry is affected, even the very financial institutions may be affected,” Kristalina Georgieva, the managing director of the International Monetary Fund, told CNBC earlier this month.

Global Starvation:

“Madagascar on the brink of climate change-induced famine” (https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-58303792)

Madagascar is on the brink of experiencing the world’s first “climate change famine”, according to the United Nations, which says tens of thousands of people are already suffering “catastrophic” levels of hunger and food insecurity after four years without rain.

The drought – the worst in four decades – has devastated isolated farming communities in the south of the country, leaving families to scavenge for insects to survive.

One of the saddest parts of the present dynamic is that people are moving in droves to places that are already experiencing major, highly visible impacts of climate change:

The effects are being felt across the West. Lake Mead, the largest reservoir in the United States, is at its lowest level since it was first filled in the 1930s. Water levels are so low that the Bureau of Reclamation, an agency of the Interior Department, declared the first-ever water shortage on the Colorado River on August 16th. Reduced snowpack in the Rocky Mountains and Sierra Nevada has turned forests into tinderboxes and fuelled wildfires. Joshua trees, though native to the desert, are parched and dying.

I have encountered this attitude before in other places, but it was almost always framed as now vs. the future. At this point, however, it seems to be a case of ignoring already present risks that will only continue to amplify. I will write more on this psychology in future blogs.