Figure 1 – Terracotta Soldiers in Xi’an

Figure 2 – Petra (Source: Britannica)

Last week’s blog focused on the finite availability of burial land and the unfulfilled wish of many of us to leave behind our stories without crowding the planet with even more stone memorials. Most of last week’s blog focused on the practices of the rich world. That blog ended with the promise that this blog would expand the coverage to include many more practices, with a particular emphasis on the global distinctions between cremation and burial. Below is a Wikipedia summary of global cremation rates:

This article is a list of countries by cremation rate. Cremation rates vary widely across the world.[2] As of 2019, international statistics report that countries with large Buddhist populations like Bhutan, Cambodia, Hong Kong, Japan, Myanmar, Nepal, Tibet, Sri Lanka, South Korea, and Thailand have a cremation rate ranging from 80% to 99%,[2] while Roman Catholic majority-countries like Italy, France, Ireland, Latvia, Poland, Spain, and Portugal report much lower rates.[2] Factors include both culture and religion; for example, the cremation rate in Muslim, Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, and Roman Catholic majority-countries is much lower due to religious sanctions on the practice of cremation, whereas for Hindu, Jain, and Buddhist majority-countries the cremation rate is much higher.[2] However, economic factors such as cemetery fees, prices on coffins and funerals greatly impel towards the choice of cremation.

However, burial practices are as old as civilization. Two of the most famous ones, still among the most active tourist attractions, are shown in Figures 1 and 2. I took Figure 1 during a visit to China in 2015, and Figure 2 comes from a Britannica entry. Below are two short descriptions of the Terracotta Soldiers in Xi’an. The travel guide includes a more general description of burying practices in China.

The Terracotta Army is a collection of terracotta sculptures depicting the armies of Qin Shi Huang, the first emperor of China. It is a form of funerary art buried with the emperor in 210–209 BCE with the purpose of protecting the emperor in his afterlife.

The figures, dating from approximately the late third century BCE,[1] were discovered in 1974 by local farmers in Lintong County, outside Xi’an, Shaanxi, China.

Since ancient times (roughly from the Shang Dynasty, lasting from 1,556 B.C. to 1,046 B.C.), Chinese people believed that the souls of the dead lived in another world: the nether world and graves were their earthly residences. Death of course brings boundless grief to the living, but the living have traditionally held grand, even extravagant funerals to see off the dead. Today, funerals are much more simple and economical.

Besides the grand funeral, people would bury some funeral objects for the dead, such as gold, silver, bronze wares, pottery, and other precious things. That’s why China has so many historical relics hidden underground and why grave robbery has been so prosperous in Chinese history.

Take the mausoleum of Emperor Qin, the largest underground mausoleum in the world for example. The mausoleum covers an area of 56 square kilometers. Up to now, more than 50,000 historical relics have been unearthed at the mausoleum. Among these historical relics, the Terracotta Warriors are the most famous ones. The site is about 2 kilometers from Emperor Qin’s Mausoleum, and they were created as the guards of Emperor Qin’s Mausoleum.

Next, we have a short Wikipedia description of the royal tombs in Petra.

The Royal Tombs of Petra embody the unique artistry of the Nabateans while also giving display to Hellenistic architecture, but the façades of these tombs have worn due to natural decay. One of these tombs, the Palace Tomb, is speculated to be the tomb for the kings of Petra. The Corinthian Tomb, which is right next to the Palace Tomb, has the same Hellenistic architecture featured on the Treasury. The two other Royal Tombs are the Silk Tomb and the Urn Tomb; the Silk Tomb does not stand out as much as the Urn Tomb. The Urn Tomb features a large yard in its front, and was turned into a church after the expansion of Christianity in 446 AD.[31]

As I’ve mentioned before, cost is also an important consideration when deciding the mode what to do with the bodies of the dead:

-

Research reveals Japan is most costly place to die sat at over two thirds the average salary

-

The average cost of dying across the world is around 10% of your annual salary

-

China is second most expensive place to die, with nearly 50% of salary

New research from SunLife, the over 50’s life insurance provider, has revealed which are the most expensive countries across the world to die in, when compared to the respective cost of living and earnings.

Based on available data gathered by its research team, the figures revealed that Japan is the most expensive place on the planet to die, with the cost of burial or cremation costing just over two thirds of the average salary, followed by China, which costs on average just below half of the yearly wage. Germany is the most expensive European country to die, but it sits far below the costs of China and Japan at only 16% cost of your overall salary.

According to the research, the average cost of a Japanese funeral is around 3 million Yen (approximately $27,900*), more than two thirds of the annual average salary in the country which equates to around $40,863 according to the latest figures from the OECD Better Life Index.

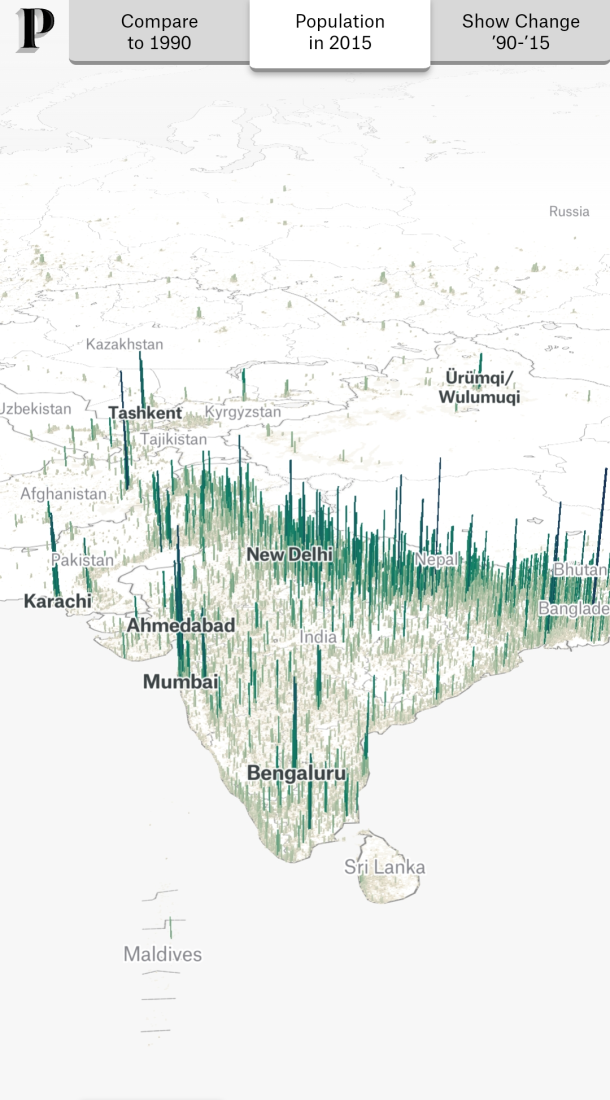

Many of our earlier ancestors believed that the world was flat. This is logical because most of the terrain around us looks flat. As we have evolved, however, many observations have shown things that could only have been accounted for with some kind of spherical shapes. All this thinking is two-dimensional (only surfaces). The Anthropocene is characterized by a third dimension, the density of humans. Figure 3 is an example of such a three-dimensional India.

Figure 3 – Population density in India (Source: Reddit)

Records about India also show that the country is running out of space for its new deaths. According to the latest census, India has just surpassed China as the most populated country, with 1.4 billion people. 80% of the population is Hindu and 14% is Muslim. However, even 14% of 1.4 billion is a large number (close to 200 million). The Hindu majority favors cremation but the article below shows that India, too, is running out of space in its cemeteries, especially given the extenuating circumstances of COVID-19:

NEW DELHI – The tombstones in the area designated for Covid-19 victims at Delhi’s biggest Muslim graveyard – the Jadid Qabristan Ahle Islam – tell a story of permanent exile. Many of the bodies here are of patients from states such as Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, individuals who came to Delhi for treatment but could not return to be buried closer to home.

The authorities in the city still do not permit bodies of Covid-19 victims to be taken back because of sanitation protocols, forcing families to bury them in Delhi’s graveyards.

This burden of interring the dead from smaller towns and rural parts of the country is one of the contributing factors to a problem for graveyards in big Indian cities – they cannot keep pace with the country’s growing Covid-19 death toll.

A similar scenario is taking place in China:

China is facing a space problem, not only for its living residents but also for its dead. While the U.S. currently has around 50,000 cemeteries, China only has about 3,000, Quartz points out, and they’re quickly filling up. Within six years, experts project that the country will run out of currently allocated space for burying people, according to Want China News.

As a result of dwindling supply for millions of aging citizens, plot prices are shooting up. One prime spot in Shanghai sold for $3.5 billion earlier this year, Quartz writes, while the average burial real estate goes for around $15,000. Prices are climbing each year, and one company that owns and manages graveyards has decided to go public, with a rumored IPO of $200 million to be announced immanently, Quartz reports. On the other hand, Want China Times reports that another company was caught selling $48 million’s worth of grave plots on the black-market.

The peaks in the density maps indicate that, at least presently, a lack of space doesn’t necessarily mean an absolute lack of space everywhere. It means a lack of more “convenient” space. Cemeteries near the places where family and friends live, which are increasingly urban places (peaks in the population density), become especially crowded. This also means that even countries with majorities that follow cremation practices, which in principle require less space, can be short of burial space that is convenient for many of its citizens.

To my knowledge, the desire to perpetuate individual stories in a cost-effective way that will go beyond the rich and powerful has yet to be fully explored. We will stay tuned (as long as we can).