Figure 1 – Map of Australia (Source: Geology.com)

Figure 1 – Map of Australia (Source: Geology.com)

Figure 2 – The three national parks around Darwin

Figure 2 – The three national parks around Darwin

My wife and I are back from a three-week vacation in Australia. In this blog, I will try to explain why we went there in the first place and why my next series of blogs will be dedicated to this trip. The trip was structured so we spent half of the time with family in Melbourne and the other half of the time in Darwin and the surrounding national parks. As strange as it sounds, both halves connected to the rapid changes that now afflict our planet, and to which this blog is dedicated. However, the connection to climate change of such a trip is unquestionably problematic: the flying distance from New York City, where we live, to Melbourne is 16,763 km (10,418 miles). In addition, the distance between Melbourne and Darwin is 3,740 km. There is no question that flying such distances is not good for the planet. To add to that, both my wife and I are of an advanced age (I am of a considerably more advanced age than my wife) and our health is fragile. Flying such distances in economy class is brutal for our bodies. Fortunately, we could afford to fly business class. By doing so, however, we doubled the environmental impact of our flights.

The main driving force that led us to take the trip was the family trip to Melbourne. My family there started with my cousin (his father and mine were brothers), who is eight years older than me, also born in Warsaw, Poland. Unlike me, he encountered the Nazi invasion at the age of 8 (I was 3 months old when the Nazis invaded Poland). He survived the Holocaust and after a few years in Israel, he ended up in Melbourne with his stepfather and his mother. A few months ago, he was interviewed in Australia about his early experiences. Recently, he lost his wife, and we felt a strong urge to spend some time with him and his family. I will dedicate a future blog to making a case for constructing massive societal family trees until we demonstrate that all of us are members of the same family and thus share responsibility for each other’s well-being.

Summer break usually gives faculty time to “rearm” themselves with developments in their fields. The trip to Darwin—and to the surrounding national parks shown in Figure 2—was designed to accomplish that while also catering to our interest in exploring unfamiliar parts of the world.

July is mid-winter in Melbourne. During our stay, we had one rainy day. It was very pleasant to walk around, but less pleasant to swim. We went to Darwin to experience something different. As can be seen in the opening map, Darwin is at the northern tip of the continent. There is no winter or summer there per se, but there is a dry and a wet season. We were there at the height of the dry season, with temperatures that we might associate with a mild summer (around 25oC or 77oF). Darwin is the capital of the Northern Territory of Australia, with relatively few residents (but a lot of tourists).

The last two blogs, one by me and the other by Sonya Landau, focused on the water stress in Arizona and its conflicts with population growth. Water stress is one of the most important impacts of climate change on Arizona and many other parts of the world. Adaptation to the dry season is one of the most important tools to adapt to climate change. The visit to Darwin taught me how nature can create wonders in the wet season and how the landscape can adapt to water stress during the dry season. The next blog will try to explore these trends further.

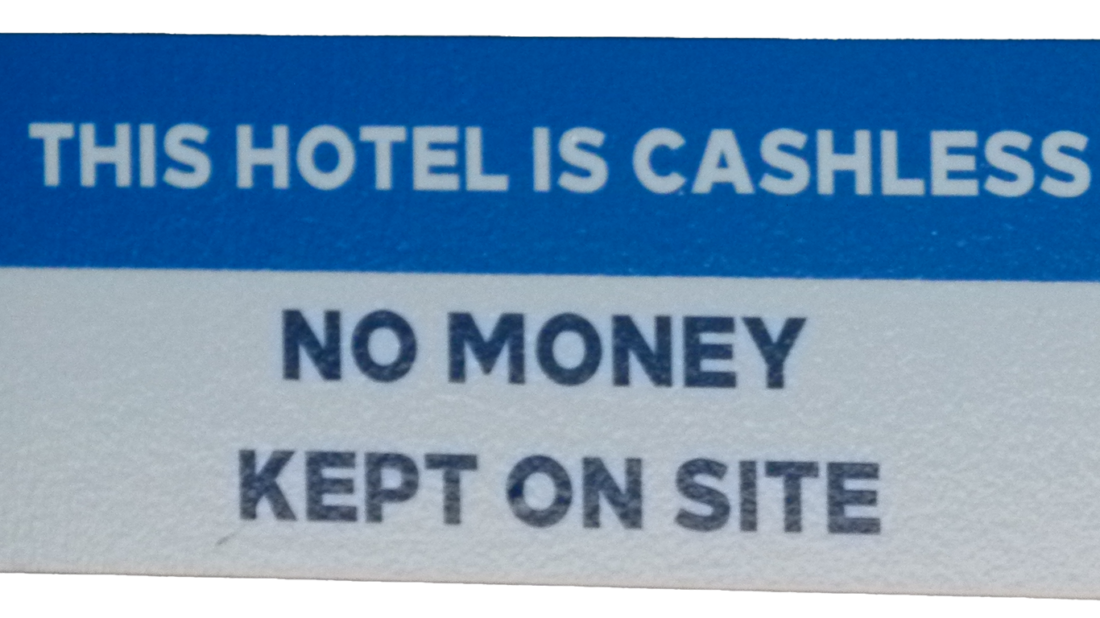

We had some surprises in Australia that have nothing to do with environmental impact and thus will not be expanded to separate blogs. The biggest surprise (at least to me) was the news that I really didn’t need to bother exchanging my American dollars for Australian ones. We were told that—at least in the places that we planned to visit—nobody uses cash. We didn’t believe our sources and got some Australian dollars anyway. It turned out our sources were right. In Melbourne, the only place that required cash was a small Chinese restaurant where we had lunch. In Darwin, at the entrance to the Hilton hotel where we stayed, there was a sign, shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3 – The “warning” on Darwin’s Hilton door

Figure 3 – The “warning” on Darwin’s Hilton door

We didn’t bother to inquire what was behind the story that made management post the sign. When we went out, the soft drink machines (shown in Figure 4) made the overall shift to a “cashless” economy clear.

Figure 4 – Soft drink machines in Darwin.

Figure 4 – Soft drink machines in Darwin.

Before leaving Australia, we had to change almost all our Australian money back to American dollars. I didn’t use the trip to start the conversation about the impact of such a shift on people who cannot open bank accounts and get credit cards, however, I have no doubt that such a conversation will start if the trend expands beyond the Australian borders.