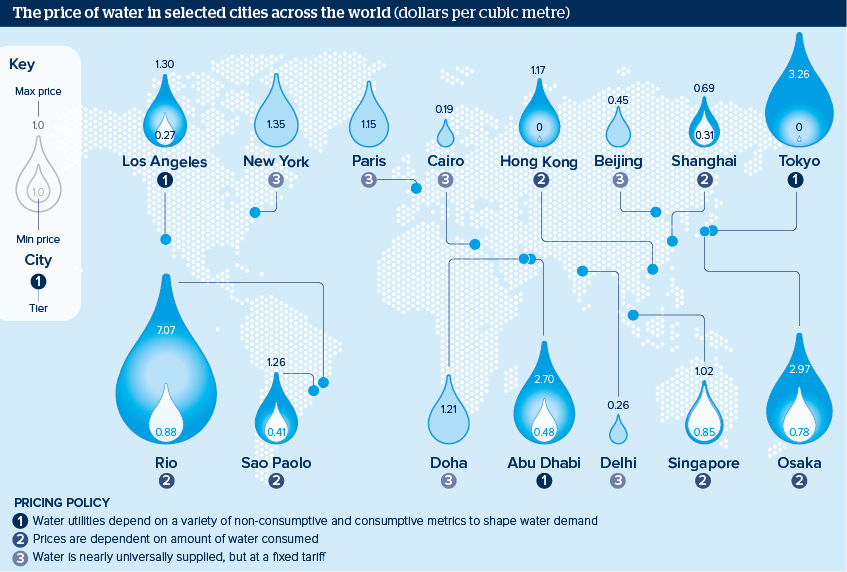

Figure 1 – The price of water in some of the world’s largest cities (Source: Municipal water utilities, Oxford Analytica)

Figure 1 – The price of water in some of the world’s largest cities (Source: Municipal water utilities, Oxford Analytica)

Figure 1, above, shows what seems to be the random distribution of the price of water in some of the largest cities from developed, developing, and intermediate-income countries. All of these cities are either located on the shore of an ocean or surround a large river that is directly connected to an ocean. Yet, the water pricing that its citizens enjoy seems random.

The most devastating disaster many of us are focusing on these days is the August 8th, climate-related wildfire destruction of Lahaina in Maui, Hawaii. As of yesterday, the death toll had reached 115, with 388 still unaccounted for. The sorrow is now being converted into anger that the destruction was a consequence of a predictable disaster that we have no idea how to handle. As one NYT article put it, “Maui Knew Dangerous Wildfires Had Become Inevitable. It Still Wasn’t Ready.” Furthermore, many of us think that now, this kind of disaster can happen everywhere, and we’d better take some lessons from it to minimize the impact.

The Maui disaster comes in the midst of record-breaking global heatwaves that the NYT describes in the following way (Extreme Weather Hits Around the World as Global Temperatures Rise):

Not all of the extreme weather events can be immediately attributed to climate change. But they reflect the hazards that much of the world needs to prepare for as El Niño, a natural weather pattern that can play out over several years, aggravates the weather extremes fueled by the burning of fossil fuels.

My “cherry-picked” comment is to emphasize the words “immediately attributed.” I will expand on this in a future blog. I will also try to expand in a future blog on what we know about the anthropogenic (human-caused) impacts of El Niño.

Two of my favorite reporters from The New York Times comment on these developments, and others, in their recent dialogue (Opinion: These Aren’t the Darkest Years in American History, but They Are Among the Weirdest). Their emphasis, like most of the rest of the press and the social networks, is on the accumulating issues with ex-president Trump and his wishes to be president again. But before going there, they start with their take on Maui and Lahaina. I have “cherry-picked” a few paragraphs from their dialogue:

Gail Collins: Maui is going to be hard for any of us to forget. Or, in some cases, forgive. There are certainly a heck of a lot of serious questions about whether the folks who were supposed to be responsible did their jobs.

Bret: There’s a story in The Wall Street Journal that made me want to scream. It seems Hawaiian Electric knew four years ago that it needed to do more to keep power lines from emitting sparks, but it invested only $245,000 to try to do something about it. The state and private owners let old dams fall into disrepair and then allowed for them to be destroyed rather than restoring them, leading to less stored water and more dry land. And then there was the emergency chief who decided not to sound warning sirens. At least he had the good sense to resign.

Gail: But let’s look at the way bigger issue, Bret. The weather’s been awful in all sorts of scary ways this summer, all around the planet. Pretty clear it’s because of global warming. You ready to rally around a big push toward environmental revolution?

Bret: I’m opposed on principle to all big revolutions, Gail, beginning with the French. But I am in favor of 10,000 evolutions to deal with the climate. In Maui’s case, a push for more solar power plus reforestation of grasslands could have made a difference in managing the fire. I also think simple solutions can do a lot to help — like getting the federal government to finance states and utilities to cover the costs of burying power lines.

Gail: Yep. Plus some more effortful projects to address climate change, like President Biden’s crusade to promote electric cars and an evolution away from coal and oil for heat.

Bret: The more I read about the vast mineral inputs for electric cars — about 900 pounds of nickel, aluminum, cobalt and other minerals per car battery — the more I wonder about their wisdom. If you don’t believe me, just read Mr. Bean! (Or at least Rowan Atkinson, who studied electrical engineering at Oxford before his career took a … turn.) He made a solid environmental case in The Guardian for keeping your old gas-burning car instead of switching to electric. But I’m a big believer in adopting next-gen nuclear power to produce a larger share of our electric power needs. And I’m with you on moving away from coal.

The unfortunate thing about both reporters waving their favorite remedies for climate change is that those have very little to do with the direct consequences of what happened in Lahaina and other similar impacts of the destructive forces that climate change brings us. When a disaster like this strikes, an often immediate reaction is to search for culprits to blame. Hanging wires from electric utilities are common candidates (see the situations in destructive fires in California (November 26, 2019). In Maui, it got worse because the fire hydrants turned out to be dry – there was no water to fight the flames. It turns out that this situation had been predicted and could have been remedied by creating water storage facilities to be reserved for that purpose as insurance. This was not done because of fear that it would impact agriculture.

Water stress and hanging utility wires have become connected to the loss of control of wildfires. To make sure that such issues are not repeated, we will all need to pay more for both utilities. This blog focuses on water. Next week’s blog will focus on hanging wires.

I addressed climate-change-triggered water stress in earlier blogs, emphasizing the local aspect of water stress. After all, in a world where 70% of the surface is covered by oceans, we cannot claim to be lacking water (reminder – Maui and all Hawaiian Islands are surrounded by the Pacific Ocean). What we can have is stress related to freshwater availability and the shifts and changes in intensity of the water cycle.

Here, in the context of the water issues in Maui, I will focus on the important role that agriculture plays in water use and how the pricing of water varies across the planet.

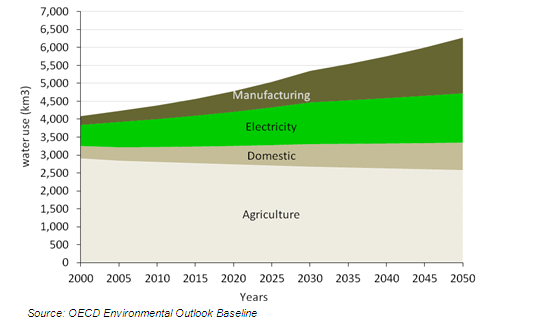

Figure 2 shows global water use by sector. Agriculture is in the lead. However, the percentage of water use in agriculture is not equally distributed.

Figure 2 – Global water use by sector (Source: OECD)

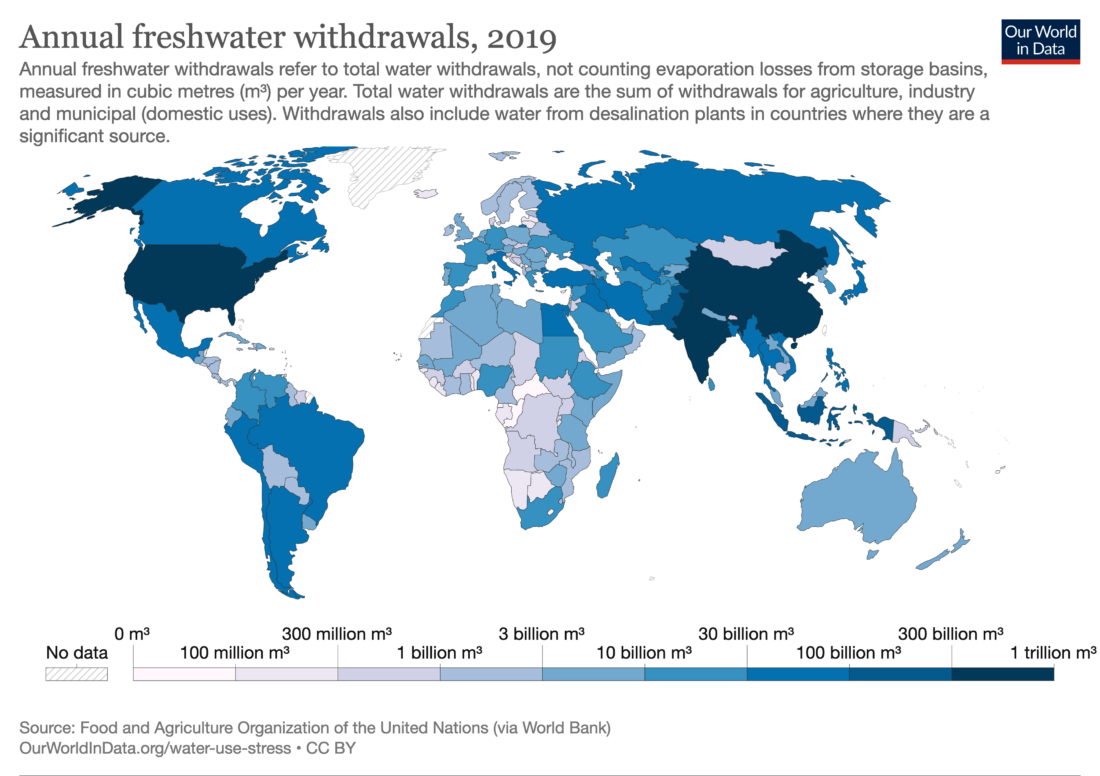

Figure 3 shows the global distribution. Developing countries bear most of the heaviest use. A good place to start revisiting the issue is in the March 4, 2014 blog, where I describe the holistic effort that Israel is putting into addressing the issue.

Figure 3 – Agricultural share of water withdrawals, 2019 (Source: Our World in Data)

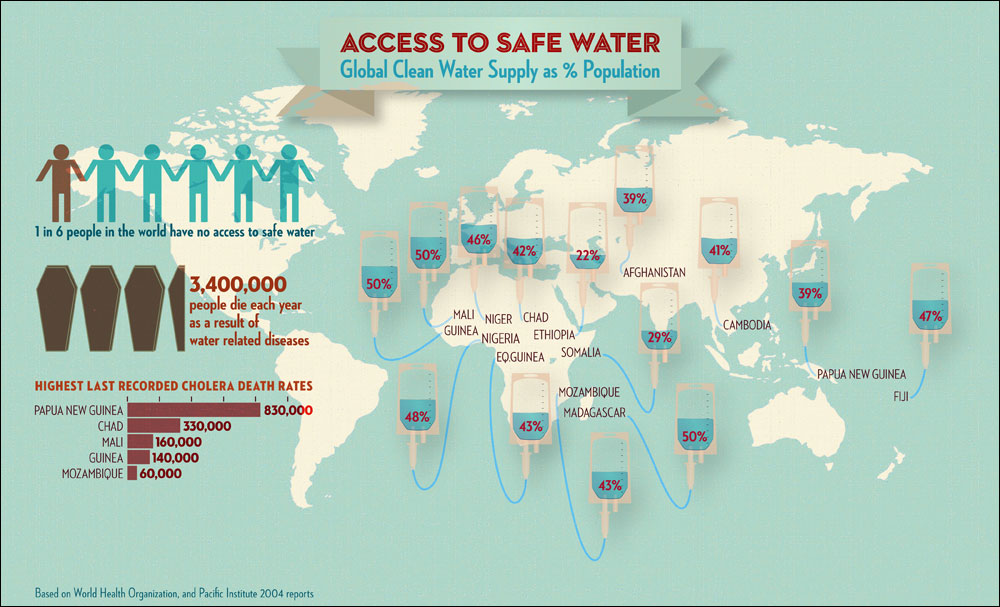

The Israeli effort is focused on recycling water locally and desalination of sea water. These processes cost money and access to sea water. Hawaii is a state of the US, the largest rich country in the world, surrounded by the water of the Pacific Ocean. If one of our states could not be prepared for such water stress, who could? Figure 4 shows that a significant fraction of the world is desperately lacking access to safe water.

Figure 4 – Global access to safe water (Source: Circle of Blue)

In an earlier blog (July 4, 2023), I showed what another state in the US, Arizona, is doing to prepare: it’s coming to an agreement with Mexico and Israel to construct a desalination plant in Mexico. The idea is to serve Arizona and limit new construction in selected areas until the water situation improves. The poor countries, such as those in Africa, don’t have that option. If the rich countries refuse to help them secure access to safe water, they may refuse to cooperate in climate change mitigation. This could mean refusing to cooperate in global efforts to lessen the probability that what just happened to Lahaina will engulf the whole planet.

we all live on planet Earth, full of minerals. but the thing that is making it difficult to live on Earth is our behavior and distribution of resources