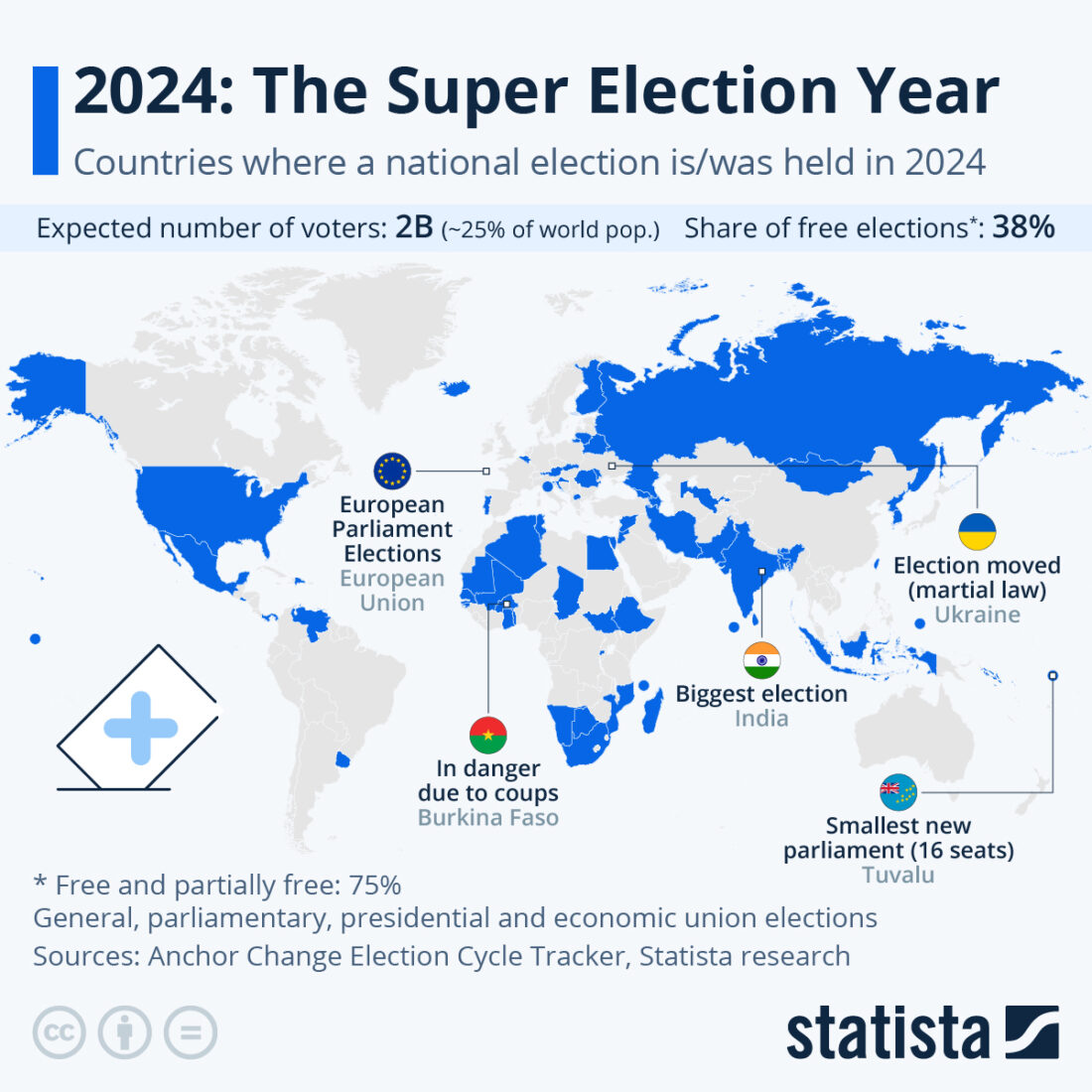

My previous blog emphasized the importance of immigration in equilibrating demographic transition in many countries with below-replacement fertility rates. However, reliance on immigration for population growth makes it a major political issue. This blog starts to explore the political ramifications. This issue attracts great attention in the US and other countries and this is a global “mega” election year, with 25% of the global population expected to participate in the voting process. The global election picture is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 – Expected national elections in 2024 (Source: Statista)

The situation in the US, which is expecting a presidential election in November, is summarized in the NYT piece by Paul Krugman:

Modern nations can’t — practically or politically — have open borders, which allow anyone who chooses to immigrate.

The good news is that America doesn’t have open borders, and there is no significant faction in our politics saying we should. In fact, immigrating to the United States legally is fairly difficult.

The bad news is that we’re having a hard time enforcing the rules on immigration, mainly because the relevant government agencies don’t have sufficient resources. And right now, the reason they don’t have those resources is that many Republicans in Congress, while fulminating about a border crisis, appear determined to deny the needed funding.

Their position is rooted in extraordinary political cynicism, and they aren’t even trying to hide it: Donald Trump has intervened with Republicans to block any immigration deal because he believes that chaos at the border will help his election prospects.

The broader international situation is summarized in this Financial Times piece:

International migration to rich countries reached an all-time high last year, driven by global humanitarian crises and demand for workers, the OECD said on Monday. The Paris-based organisation estimated 6.1mn new permanent migrants moved to its 38 member countries last year, 26 per cent more than in 2021 and 14 per cent higher than in 2019, before the pandemic brought an enforced pause to much cross-border movement. Preliminary figures for 2023 suggested a further increase, the OECD said, indicating that last year’s surge was not solely a post-Covid rebound. This total did not include a further 4.7mn displaced Ukrainians who were living in OECD countries as of June this year; an increase in temporary migration for work; or a record 1.9mn permits issued to international students — with the greatest number of new students going to the UK. Both humanitarian and labour-related flows of people look set to continue at high levels, with the latter accounting for a growing share of total migration, driven by a widespread scarcity of workers, the OECD said.

Previous blogs focused on some of the impacts of declining populations. The global population transition features some countries where the fertility rate is well below replacement and others where it is above replacement. There are examples of poor and rich nations in both of these categories.

The increased reliance on immigration is a serious threat to many in both poor and rich countries. Not surprisingly, however, the threats are different. Emigration from poor countries to rich ones is often selective. Rich countries with serious fertility deficits encourage well-educated immigrants, a process often described as a brain drain. As mentioned in previous blogs, over the last 30 years, almost all countries have instituted compulsory education. The prospect of economic progress through education has become universal but for countries with limited resources, the process is expensive. Rich countries with decreasing populations can offer much better compensation to educated immigrants, as compared to their native countries, a strong incentive to immigrate. The Yahoo article below offers recent coverage of this issue:

In the global context, attracting and retaining specialized talent is paramount for economic growth. Recent immigration policy changes, such as Ireland’s expanded employment permits and the EU Blue Card enhancements, demonstrate efforts to facilitate foreign national movement. The introduction of remote work visas and visa waivers by various countries further showcases a concerted effort to attract and accommodate foreign talent, underscoring the strategic measures in place to address the complex issue of brain drain on an international level. U.S. has been a focal point in context of emigration. In 2022, the workforce in the United States consisted of approximately 28.4 million immigrant employees, showcasing a notable increase of nearly 7 million from the 21.5 million recorded in 2010. Comparatively, there were approximately 129.4 million native-born workers in the same year. Among the various industries, the educational and health services sector employed the highest number of immigrant workers, totalling 5.2 million individuals, which accounted for 18.2% of all foreign-born employees.

In the first blog in this series, I showed that below-replacement fertility is not a “prerogative” of rich countries anymore; it is starting to affect poor countries as well. Part of the reason is that most immigrants from poor countries to rich ones are relatively young, within the reproductive ages of females. This starts to be an important factor in the declining fertility of these countries. A recent article by the New York Times uses Bosnia as an example of such dynamics:

Nowhere, however, have demography and the politics around it been as fraught as in Bosnia, a small, ethnically fractured nation. Like many poorer countries, it has a high rate of emigration, which surged during the 1992-95 war. But it also has an extremely low birthrate, a phenomenon usually associated with richer countries.

An additional strong driving force for people to immigrate from their native country to a “better” place is their governments’ failure to govern effectively. One important indicator of a failed government is uncontrolled inflation. An infographic of global inflation rates was recently published based on IMF (International Monetary Fund) data. The ten countries with the highest inflation rates are Venezuela (230%), Zimbabwe (190.2), Sudan (127%), Argentina (69.5%), Turkey (54.3%), Egypt (25.9%), Angola (25.6%), Iran (25%), Ethiopia (18.5%), and Pakistan (17.5%).

Given my Holocaust history (put the word in the blog’s search box), I find that the most frightening aspect of the public attitude’s increased role in global immigration is not focused on poor countries but on rich ones. It has to do with “replacement theory.” The background of the various aspects of this theory (a better word for this should be “attitude”) is summarized in the two excerpts given below:

The idea of “replacement” under the guidance of a hostile elite can be further traced back to pre-WWII antisemitic conspiracy theories which posited the existence of a Jewish plot to destroy Europe through miscegenation, especially in Édouard Drumont‘s antisemitic bestseller La France juive (1886).[51] Commenting on this resemblance, historian Nicolas Lebourg and political scientist Jean-Yves Camus suggest that Camus’s contribution was to replace the antisemitic elements with a clash of civilizations between Muslims and Europeans.[16] Also in the late 19th century, imperialist politicians invoked the Péril jaune (Yellow Peril) in their negative comparisons of France’s low birth-rate and the high birth-rates of Asian countries. From that claim arose an artificial, cultural fear that immigrant-worker Asians soon would “flood” France. This danger supposedly could be successfully countered only by increased fecundity of French women. Then, France would possess enough soldiers to thwart the eventual flood of immigrants from Asia.[52] Maurice Barrès‘s nationalist writings of that period have also been noted in the ideological genealogy of the “Great Replacement”, Barrès contending both in 1889 and in 1900 that a replacement of the native population under the combined effect of immigration and a decline in the birth rate was happening in France.[53][51]

Britannica – What and where it is taking place

Replacement theory, in the United States and certain other Western countries whose populations are mostly white, a far-right conspiracy theory alleging, in one of its versions, that left-leaning domestic or international elites, on their own initiative or under the direction of Jewish co-conspirators, are attempting to replace white citizens with nonwhite (i.e., Black, Hispanic, Asian, or Arab) immigrants. The immigrants’ increased presence in white countries, as the theory goes, in combination with their higher birth rates as compared with those of whites, will enable new nonwhite majorities in those countries to take control of national political and economic institutions, to dilute or destroy their host countries’ distinctive cultures and societies, and eventually to eliminate the host countries’ white populations. Some adherents of replacement theory have characterized these predicted changes as “white genocide.

The replacement fantasy received much wider attention in the early 21st century with the publication of Le Grand Remplacement (2011), by the French writer and activist Renaud Camus. He argued that since the 1970s, Muslim immigrants in France have shown disdain for French society and have been intent on destroying the country’s cultural identity and ultimately replacing its white Christian population in retaliation for France’s earlier colonization of their countries of origin. He also asserted that the immigrant conquest of France was being covertly abetted by elite figures within the French government. Camus’s sobriquet for his conspiracy theory, the “great replacement,” proved attractive to many right-wing activists and scholars in France, and his rhetoric and the substance of his theory were eventually adopted by leaders within the mainstream of French political conservatism, including Marine Le Pen, the leader of the right-wing National Rally (formerly National Front) party. The great replacement was soon espoused by right-wing parties and extremist groups in other European countries—notably including Hungary, where it was explicitly endorsed by the country’s authoritarian prime minister, Viktor Orbán.

Replacement theory has been widely ridiculed for its blatant absurdity. It has been just as widely condemned for its encouragement of racist violence through its toxic allegation that nonwhite immigrants (as well as the Jewish figures who allegedly direct their immigration) pose an existential threat to whites. The latter criticism has been tragically validated by the occurrence of several mass murders in the United States and other countries by white racists who clearly indicated their adherence to replacement theory before or after their attacks.

Within the US, opponents of immigration often claim that only criminals leave their native countries to prey on the peaceful citizens of rich countries. Given a massive influx of 1.6 million immigrants in 2023 (legal and illegal), it is not difficult to cherry-pick “proof” of this concept. Such a case emerged with the killing of the University of Georgia nursing student. Below is what MSN wrote about the political ramifications of this case:

Donald Trump’s presidential campaign moved quickly to tie the killing of a Georgia nursing student, allegedly by a Venezuelan migrant who entered the country illegally in 2022, to the surge of undocumented immigrants at the southern border under the Biden administration. His campaign posted a video that, with pounding music, combines news clips about the case with clips of Biden administration officials assuring people that the border was secure…

A 2020 study, published by the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, analyzed 200,000 congressional speeches and 5,000 presidential communications on immigration since 1880, when a wave of Chinese immigrants led to the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 that barred Chinese laborers. When lawmakers spoke about immigration, their speeches were twice as likely as their speeches on other topics to mention words related to crime.

Moreover, the study found “stark differences” in how lawmakers discussed European and non-European groups, with “more implicitly dehumanizing metaphors” used to describe Chinese, Mexicans and other non-Europeans. “There is also a striking similarity in the use of explicit frames, with a greater emphasis on ‘crime,’ ‘labor,’ and ‘legality’ for the non-Europeans and less on ‘family,’ ‘contributions,’ ‘victims,’ and ‘culture,’” the study said.

In next week’s blog, I will try to shift my emphasis to our more general rational decision-making capabilities.