Throughout the more than 12 years that I have been writing this blog, my emphasis has been on trying to identify and analyze what I see as evolving global trends that can help both students and others navigate through changing realities. I have not always been consistent in my way of presenting these realities. In almost all cases, I have tried to quantify the trends and present the results either in terms of a figure and/or using individual sovereign countries to illustrate the changes. Two recent examples make these points: last week (August 13th), the emphasis was on global digitization (access to computers), to illustrate global technology penetration. I assembled a table similar to Table 1 below. Earlier this year (January 30th), the emphasis was on global changes in the fertility rate and I included many more developed countries than Table 1 shows. The main difference was that my objectives in compiling these data were different. Showing computer access, my objective was to represent global trends with an emphasis on emerging countries, while the table that shows the decline of fertility was meant to show important issues that are more abundant in developed countries. Both tables included the population and recent GDP/capita of the selected countries.

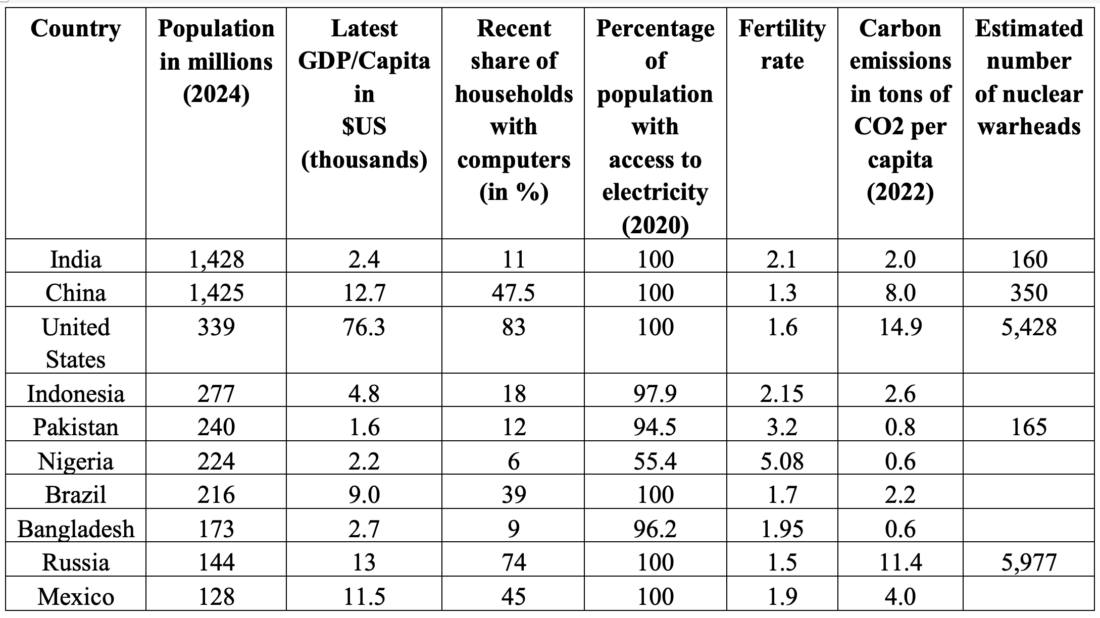

In this blog, I am including Table 1, based on a compilation of recent population and GDP/capita. I showed last week that the 10 listed countries simultaneously account for more than 50% of the global population and more than 50% of GDP and thus fairly represent our world. In this table, I have included 5 recent trends that were discussed in previous blogs (put them in the search box to scan through the examples). The 5 trends include computer access, electricity access, fertility, carbon emissions, and estimated number of nuclear warheads. All five trends are anthropogenic (generated by us humans). All five have a major impact on our lives and all of them started in my lifetime. Each trend has a set of complex impacts, with both destructive and positive potential. The impact they have on our lives is projected to increase.

Table 1 – Recent trends in 10 large countries that exceed 50% of the global population (4.5 billion people) and 50% of the global GDP (55 trillion $US). The approximate global population is taken as 8.2 billion and the approximate global GDP is approaching 110 trillion US$.

(The data for the nuclear warheads were taken from the March 22, 2022 blog and the data for the carbon emissions per capita were taken from the carbon offsets website COTAP.org.

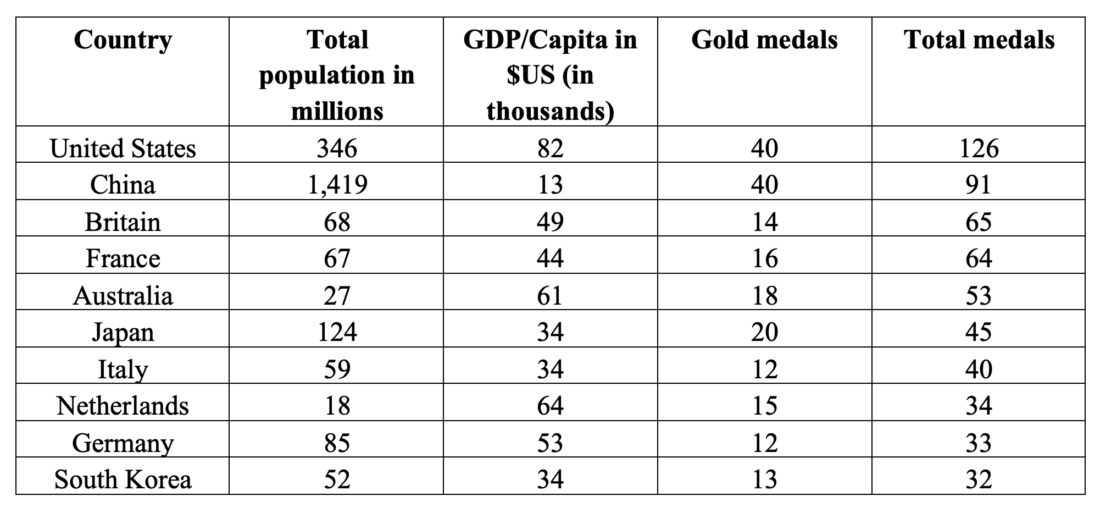

Using a similar format, I have compiled a similar table of the 10 countries that won the most medals (both gold and total) in the recent Paris Olympic Games that just finished. The objective was the same: to explore what a concentrated list of the 10 top medal winners can teach us about the world at large.

Table 2 – The 10 countries from which athletes collected the largest number of medals in the 2024 Paris Olympic Games

The Olympics had a total number of 329 medal events in 32 sports. There were three medals: gold, silver and bronze. Taking the recent global population to be 8.2 billion and the recent global GDP as approaching 110 trillion $US, the 10 countries listed in Table 2 account for 28% of the global population and 63% of the global GDP. Combined, these 10 countries won 61% of the gold medals and 59% of all the medals.This closely matches the 10 countries’ share of the GDP (63% of the population to 61% and 59% of the medals) but lags considerably behind their combined share of the global population.

The recent summer Olympic Games are the fourth Games that I have briefly covered, starting with the ones in 2012 (see August 27, 2012; September 8, 2016 and August 17, 2021 blogs for previous Games). Each event came with different perspectives.

Unlike the 5 trends that I have compiled in Table 1, the Olympic Games didn’t start in my lifetime. A short history is described in Wikipedia with the following two paragraphs:

The modern Olympic Games (OG; or Olympics; French: Jeux olympiques, JO)[a][1] are the world’s leading international sporting events. They feature summer and winter sports competitions in which thousands of athletes from around the world participate in a variety of competitions. The Olympic Games are considered the world’s foremost sports competition, with more than 200 teams, representing sovereign states and territories, participating. By default, the Games generally substitute for any world championships during the year in which they take place (however, each class usually maintains its own records).[2] The Olympic Games are held every four years. Since 1994, they have alternated between the Summer and Winter Olympics every two years during the four-year Olympiad.[3][4]

Their creation was inspired by the ancient Olympic Games, held in Olympia, Greece from the 8th century BC to the 4th century AD. Baron Pierre de Coubertin founded the International Olympic Committee (IOC) in 1894, leading to the first modern Games in Athens in 1896. The IOC is the governing body of the Olympic Movement, which encompasses all entities and individuals involved in the Olympic Games. The Olympic Charter defines their structure and authority.

I observed (through TV, I couldn’t get there) these Olympics as much as I could. I thought that France did a magnificent job organizing this event. I was delighted that despite the unrest that France experienced before the Olympics, there were no signs of unrest during the event. Others share my opinion: NYT: Merci, Paris: We needed these Olympics:

Every venue, every day, every event. Full, alive, loud and proud. From the opening ceremony on, the French filled the cup till it runneth over, delivering an Olympic Games that mixed art with sport, and history with future, and national flag-waving with a worldwide welcoming.

For those who watched, and especially those who attended, these were the Games we needed. The Pandemic Olympics were still so vivid at the start of Paris 2024. The 2020 Games were played in 2021, and while broadcast all over the world, were seen live by almost no one. It was the anti-Olympics. As American rower Nick Mead put it: “Part of the Olympic experience is meeting all these people from all over the world, who are doing what you’re doing, maybe in a different sport or a different country, to have that same lifestyle.” The Games bring them together and introduce them all to the world.

And MSN: Why Paris 2024 Was the Most Important Olympics in Recent History:

The moment Zaho de Sagazan hit the opening note of Sous le Ciel de Paris, a great weight was lifted from the sporting world’s shoulders. Nineteen days of fierce competition, outrageous showmanship, and world record-breaking efforts officially complete, the 2024 Paris Olympic Games had finally drawn to a triumphant close. For the athletes gathered in the Stade de France for the closing ceremony on Sunday night, the sound of 70,000 cheering fans was enough to make the lifetime of training, sacrifice and dedication feel worth it, but for the city itself, the deafening roars of approval may as well have been sighs of relief. Amid all the speculation and anticipation, it had been a Games that went off largely without a hitch.

The next Olympics is scheduled for the summer of 2028 in LA, well within the next presidential tenure of the winner of the November election. I hope that both ex-president Trump and VP Harris will tell all of us, before the November elections, how they intend to help LA to run it as well as Paris did. The next blog will focus on the role that college campuses play in the success of Olympic Games.