Last week I tried to analyze the recent Paris Olympics by using a similar methodology to that I used to analyze global trends such as climate change, fertility decline, digitization, global penetration of electricity, and the use of nuclear energy. These trends were quantified and analyzed in the 10 most populated countries, which together represent more than 50% of both the global population and the global GDP. Similarly, the Paris Olympics were analyzed through 10 countries from which athletes, collectively, won 61% of the gold medals and 59% of the total medals. These 10 countries were analyzed in terms of their collective population (28% of present global population) and collective GDP (63% of global GDP). This analysis shed light on the issue that the Paris Olympics winners mostly came from the countries with the top GDPs. A similar analysis of future Olympics (starting with the Los Angeles Olympics in 2028) will show us if we are making progress in making the Olympics more inclusive by serving a higher percentage of the global population.

An interesting example of such progress can come from a different global trend: gender equity. Table 1 shows the share of males and females in the recent 10 Olympic games, compared to the first modern game that took place in Athens in 1896. We started with all-male games and ended in the “promised land”: full equity in athletic participation in the Paris Olympics.

Table 1 – Trends in share of athletes of each gender in the last 10 Olympic Games and the first modern Games in Athens (Source: Statista)

| Olympics | Male (%) | Female (%) |

| Athens 1896 | 100 | 0 |

| Seoul 1988 | 73.9 | 26.1 |

| Barcelona 1992 | 71.8 | 28.8 |

| Atlanta 1996 | 66 | 34 |

| Sydney 2000 | 61.8 | 38.2 |

| Athens 2004 | 59.3 | 40.7 |

| Beijing 2008 | 57.6 | 42.4 |

| London 2012 | 55.8 | 44.2 |

| Rio 2016 | 55 | 45 |

| Tokyo 2020 | 51.2 | 48.8 |

| Paris 2024 | 50 | 50 |

In terms of medal winners, we are very far from equity (defined as fully scaled with population – equal global chance of producing a medal winner, independent of geography). However, in terms of performance, life is more complicated.

One important reason is that in order to be an Olympic medal winner, you have to be both very gifted and extensively trained. The two are obviously connected. Superb training enhances achievements but the ability to pay for the training is concentrated in rich countries. Since winning medals gain prestige, rich countries are happy to spend the money to attract promising athletes from emerging countries. To partially counter these trends, the Olympic committee limits the number of athletes from each country in most sports and allows people with dual citizenship to choose the country that they will represent. Rich countries may facilitate citizenship applications from gifted athletes from poor countries and thus encourage emigration similar to the “brain drain” that was described before in a different context (See “Back to the Energy and Population Transitions: Electrification and Brain Drain,” February 1, 2022). On the other hand, gifted athletes from rich countries who either didn’t make the team or didn’t want to represent their original rich country, have an option to represent more needy emerging countries.

American colleges play a central element in that dynamic:

At the 2024 Paris Olympics, 272 former, current and incoming NCAA student-athletes combined to earn 330 medals for 26 countries. The medalists competed in 21 Olympic sports and represented 90 schools and 22 conferences.

Of the medals earned by athletes with NCAA ties, 127 were gold, 95 were silver and 108 were bronze. Women accounted for 58% of all NCAA medalists and 80, or 63%, of the 127 gold medals.

The United States included the most NCAA medalists of any country, with 184 medalists.

Details about the dominant American colleges in the medal distribution can be found in (NCAA’s comprehensive Olympic qualifier dashboard):

Top five NCAA (National Collegiate Athletic Association) schools, by number of medals

- Stanford: 34 medals won by 22 medalists — 12 gold, 11 silver, and 11 bronze

- California: 17 medals won by 13 medalists — 4 gold, 6 silver, and 7 bronze

- Texas: 16 medals won by 13 medalists — 7 gold, 7 silver, and 3 bronze

- Virginia: 15 medals won by 8 medalists — 7 gold, 5 silver, and 3 bronze

- Southern California: 13 medals won by 12 medalists — 6 gold, 2 silver, and 5 bronze

Top teams/countries based on NCAA athletes are listed below:

- United States: 385 athletes from 138 schools, 45 conferences, and 19 NCAA sports

- Canada: 132 athletes from 69 schools, 19 conferences, and 13 NCAA sports

- Australia: 44 athletes from 32 schools, 13 conferences, and 7 NCAA sports

- Nigeria: 38 athletes from 35 schools, 10 conferences, and 3 NCAA sports

- Jamaica: 34 athletes from 25 schools, 11 conferences, and 2 NCAA sports

- Germany: 34 athletes from 33 schools, 14 conferences, and 7 NCAA sports

Colleges and universities in the US are willing to spend large sums of money to acquire the best training facilities and best trainers to attract the best athletes from all over the world. The athletes benefit by getting a good education as well as celebrity that could help them with post-college opportunities.

However, these dynamics might slow down as we move to the next Olympics in LA. As was discussed in previous blogs, many colleges now face declining enrollment and schools need to economize—and in some cases close—to accommodate these changes.

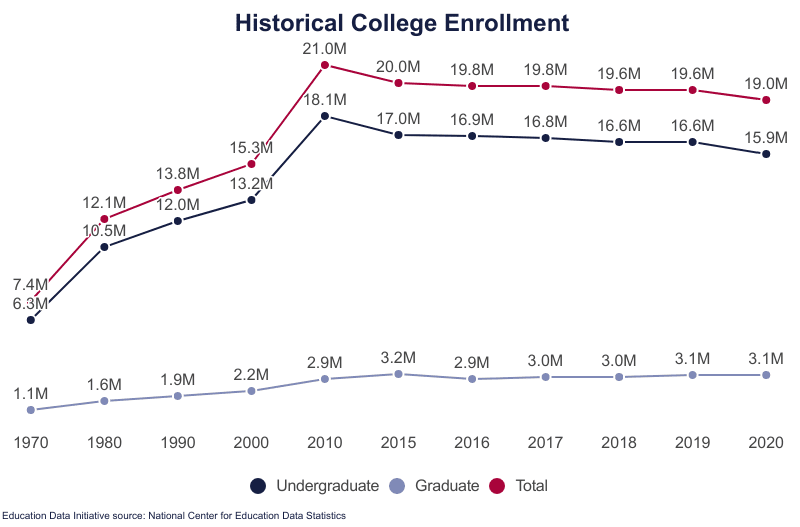

The issue was discussed in the October 10th and October 31, 2023 blogs. These blogs also discussed some of the steps that colleges are taking to counter this trend. Figure 1, taken from the October 10th blog, shows the trend.

Figure 1 – Historical US college enrollment from 1970-2020 (Source: Education Data Initiative)

A major factor in the drop in enrollment comes from the drop in fertility that was discussed in earlier blogs. The first impact of a drop in fertility is a drop in the age population of present and future college students. Most college students are Generation Z (born from 1995 – 2012). Per definition, the present drop in fertility directly impacts generation Alpha (born from 2013 – 2025). By the time of the LA Olympics, most college students will be generations Alpha and Z. The drop in enrollment will probably continue as colleges continue to economize. College administrators will have to decide how and where to balance tight budgets. Athletic fields will not escape those cuts entirely, and American colleges will likely become somewhat less attractive for athletes.