The June 9, 2015 blog focused on traditional NIMBY arguments in the context of attitudes toward wind farms. The main issue I raised was that if we are making the statement that we object to wind farms because they are an ugly view from our window, we need to clarify what we are comparing them to in terms of unsightliness. The acronym NIMBY stands for Not In My Back Yard and refers to placement – we recognize that the wind farms are needed – that the power they generate is essential – but we want it to be placed somewhere else that doesn’t inconvenience us personally. I want to discuss how we can try to expand this concept (and how to combat it) to a more general business strategy.

Why didn’t I raise this issue in a blog that immediately followed my June 9th post? As you probably noticed, the June 16th blog was a guest blog by the incredibly talented Sofia Ahsanuddin that provided a parallel insight to a previous guest blog by the similarly talented Denis Ladyzhensky. His looked at application of the Jewish tradition of blessing food to blessing the more general environment as we extract resources for human benefits. Guest bloggers operate with their own time constrains that we have to accommodate if we want to benefit from their input. Following Sofia’s blog came Pope Francis’ sweeping (and timely) encyclical. Now I am safely in China, happily removed for four weeks from pressing immediate events to focus on.

Back to NIMBY and business. The issue came up when I read a short article on Berkshire Hathaway:

In a strategy document written by SVP Brent Gale for a legal conference in July, Berkshire Hathaway Energy outlined its position on net metering, saying it should be scrapped in favor of a system that recognizes utility fixed-grid costs and utilizes distributed generation at times when it’s needed most.

So, Berkshire Hathaway Energy is in favor of scrapping net metering. The large picture behind this short paragraph quickly emerged.

First, though, what is net metering?

Net metering is a billing mechanism that credits solar energy system owners for the electricity they add to the grid. For example, if a residential customer has a PV system on the home’s rooftop, it may generate more electricity than the home uses during daylight hours.

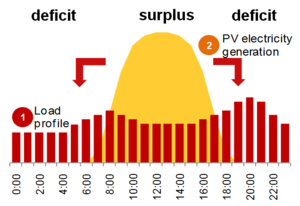

I discussed some aspects of this issue in a previous blog (December 9, 2014), with regards to the energy transition in Germany. It is one of the most crucial tools that policy makers can implement to move energy sources from the present large dependence on fossil fuels to a more sustainable mix of wind and solar. The main difficulty here is that these sources are intermittent, so matching supply to demand through load leveling requires major effort. The required matching, as applied to photovoltaic cells, can be viewed in the figure below.

Figure 1 – Typical photovoltaic daily power production and consumption

Figure 1 – Typical photovoltaic daily power production and consumption

Significant power generation takes place in midday while significant use takes place during the morning or evening. This matching can be accomplished in one of two ways: either store the surplus energy from midday to be used when supply is not available by using batteries or use your utility company as your battery by transferring the excess power and be paid by the utility for this power usually requiring the utility to pay the same price as consumer pays for getting the power. This is net metering.

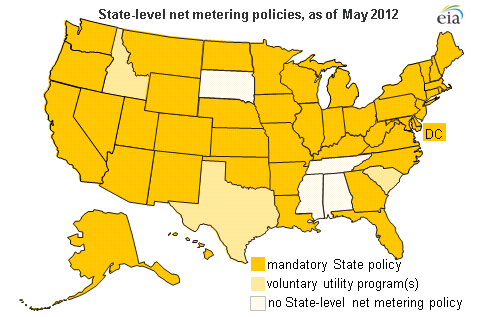

The map below shows that most states in the US now require the utilities to allow net-metering. Figure 2 – Net metering requirements across the US

Figure 2 – Net metering requirements across the US

Net metering is very convenient for customers because it doesn’t require them to buy and assemble storage facilities but it is just as inconvenient for electric utility companies.

Here is one good example of the ramifications :

Tesla Chief Executive Elon Musk introduced a new family of batteries designed to stretch the solar-power revolution into its next phase. There’s just one problem: Tesla’s new battery doesn’t work well with rooftop solar—at least not yet. Even Solar City, the supplier led by Musk, isn’t ready to offer Tesla’s battery for daily use.

The new Tesla Powerwall home batteries come in two sizes—seven and 10 kilowatt hours (kWh)—but the differences extend beyond capacity to the chemistry of the batteries. The 7kWh version is made for daily use, while its larger counterpart is only intended to be used as occasional backup when the electricity goes out. The bigger Tesla battery isn’t designed to go through more than about 50 charging cycles a year, according to SolarCity spokesman Jonathan Bass.

Here’s where things get interesting. SolarCity, with Musk as its chairman, has decided not to install the 7kWh Powerwall that’s optimized for daily use. Bass said that battery “doesn’t really make financial sense” because of regulations that allow most U.S. solar customers to sell extra electricity back to the grid.

German electric utility companies made the same kind of complaints when strategies for adaptation came up; arguments which subsequently became the source of Berkshire Hathaway Energy’s objections. A quick look at Berkshire Hathaway reveals broad ownership of utility companies, energy companies and insurance companies, so net metering strikes close to home. Warren Buffett, who runs Berkshire Hathaway, is one of the most open minded chief executive billionaires in terms of global thinking, and is known as the “Oracle from Omaha” for his investment skills:

The word “oracle” comes from the Latin verb ōrāre “to speak” and properly refers to the priest or priestess uttering the prediction. In extended use, oracle may also refer to the site of the oracle, and to the oracular utterances themselves, called khrēsmoi (χρησμοί) in Greek.

Oracles were thought to be portals through which the gods spoke directly to people. In this sense they were different from seers (manteis, μάντεις) who interpreted signs sent by the gods through bird signs, animal entrails, and other various methods.

The most important oracles of Greek antiquity were Pythia, priestess to Apollo at Delphi, and the oracle of Dione and Zeus at Dodona in Epirus.

The moniker implies an ability to clearly see the future which most of us lack. If he truly is the Oracle from Omaha, one might think that he can also clearly analyze the future impacts of climate change. But trying to pinpoint his positions regarding climate change through his various announcements calls to mind the notoriously blurred predictions of Greek oracles, and one starts to realize that his predictions are carefully tailored to serve his present business interests – with a classic NIMBY slant.