Right now, in the energy transition, there is an emerging weaponization of energy. Russia’s confrontation with the West over Ukraine is the present focal point. The following two publications provide some details:

“What Happens if Russia Cuts Off Europe’s Natural Gas?” – The New York Times

While Russia masses troops and military equipment near its border with Ukraine, parallel tensions have been building in world energy markets.

It is not hard to see why. Natural gas flowing through a web of pipelines from Russia heats homes and power factories across much of Europe. Russia is also one of the continent’s key sources of oil.

Now Western officials are considering what happens if Moscow issues a doomsday response to the tensions — a cutoff of those gas and oil supplies, in the depths of Europe’s winter.

The standoff over Ukraine comes at an inopportune time. World energy prices are already elevated as supplies of oil and natural gas have lagged the recovery of demand from the pandemic.

Russia Isn’t a Dead Petrostate, and Putin Isn’t Going Anywhere – The New York Times Opinion

Some may see Russia’s actions as the last gasp of a fading petrostate before the energy transition robs the country of geopolitical power. But that would be wishful thinking. The transition to a clean energy economy may actually empower Vladimir Putin, Russia’s president, and other petrostate leaders before it diminishes them.

In a world that is “net zero” on its carbon emissions, major fossil fuel producers — especially Russia — will be greatly diminished in their power, assuming they do not find a way to remake their economies in the interim. But in the next 10 to 20 years, the energy transition will make opportunities for petrostates to wield significant geopolitical and economic power. There are at least three reasons this is the case.

Petrostates obviously have the ability to use energy supply as a weapon, one reason that they are also the most desperate to slow the transition away from fossil fuels. I am sensitive to these dynamics. I have mentioned often on this blog that I grew up in Israel. At the time, Israel was surrounded by petrostates that were in a state of war with my country, trying to weaponize their energy. As a student, I chose to specialize in alternative energy use—not because of climate change but in an attempt to help develop alternatives to the state’s energy supply.

Below is how Wikipedia defines petrostates:

A petrostate is a nation whose economy is heavily dependent on the extraction and export of oil or natural gas. The presence alone of large oil and gas industries does not define a petrostate, as countries like Norway, Canada, and the United States are major oil producers, but also have diversified economies.[1] Petrostates also have highly concentrated political and economic power, resting in the hands of an elite, as well as unaccountable political institutions which are susceptible to corruption.[2]

While the largest oil-producing states are often petrostates, this is not always true. In 2014, for example, the United States and Canada were among the top-five oil producing countries, but are not defined as petrostates due to their diverse economies.[1] Various countries have been identified as current or former petrostates:[2][1]

Although Norway, the US, and Canada are among the largest exporters of fossil fuels, their economies are diversified, meaning that they can handle fluctuations of the energy markets much better than the countries Wikipedia defines as petrostates. Before the pandemic and the emergence of the Russia-Ukraine crisis, The Economist ran an article with some updated data about the need for energy producers to diversify:

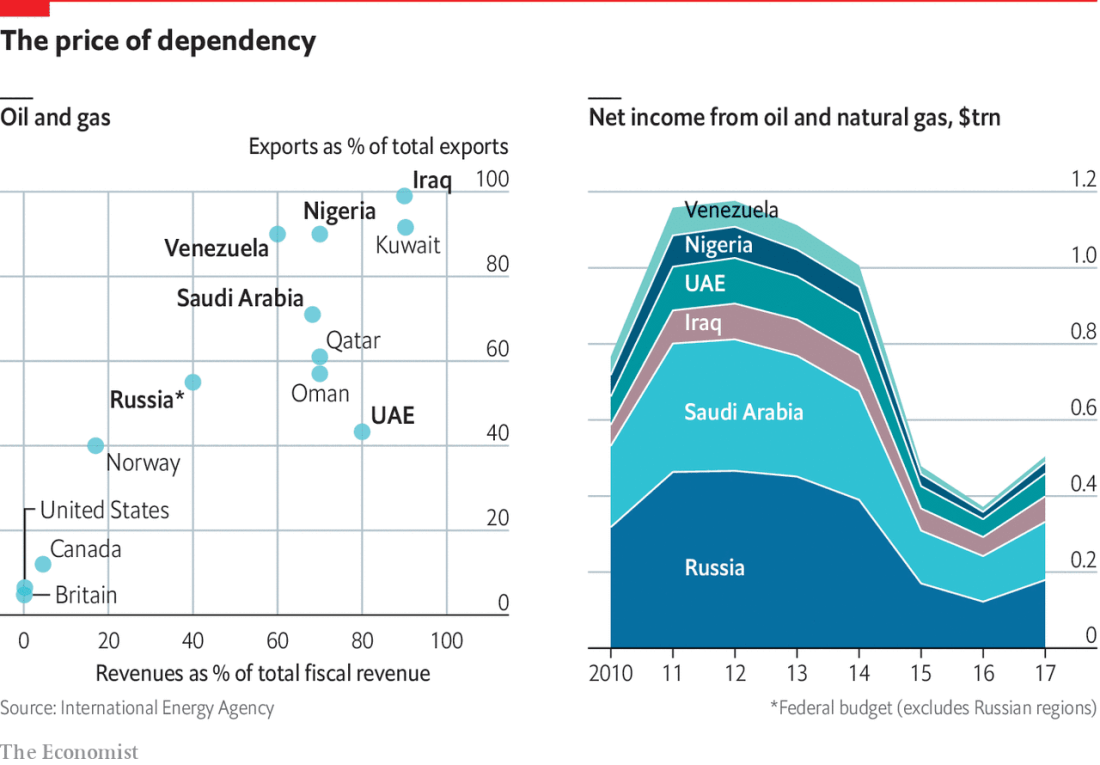

Figure 1 – The dependency of major energy producers on income from energy exports

Revenues from oil and natural gas have plunged in recent years, as prices have fallen. A new report from the International Energy Agency (IEA) puts the challenge in stark relief. In six large petrostates the IEA examined—Iraq, Nigeria, Russia, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and Venezuela—net income from oil and natural gas in 2016 was less than one-third of its level in 2012. Such a huge drop-off is painful. In Russia, oil and gas receipts account for about 40% of the government’s revenue. In Iraq they account for 90%.

The response to sinking prices has varied. Many countries ran deficits rather than slash their generous domestic spending programmes. Bahrain requires a crude price of $113 a barrel to support its budget, according to MUFG, a bank. But most countries have started talking more earnestly about diversification. Fatih Birol, director of the IEA, predicts that countries’ efforts will gain more urgency for two reasons.

Russia stands out in this analysis both in terms of its dependence on this income and the income’s changes over time.

I have repeatedly emphasized the need to pay attention to both the winners and losers of the various transitions that we are going through— (see for example, “Winners and Losers: COVID and Coal” from February 9, 2021; “Yellow Vests, Al Gore, President Trump, Conflicts Between Present and Future” from December 18, 2018; and “Wisdom from Germany: How to Transition Away from Coal” from October 8, 2019).

As the current crisis with Russia shows, the price of not paying attention to the losers can be deadly.