The last three blogs examined the state of science in assigning attributions for extreme weather events to climate change. We have found that while this science is young when it comes to local events, it’s definite in terms of global impacts. Today’s blog is focused on public, non-scientific responses to the issue—this is a topic that I have covered extensively throughout the more than 10 years that I have been writing this blog. Just paste public attitude to human attribution to climate change into the search box and you will get a handful. A Pew Research survey from 2019 gives some details:

Majorities of Americans say the federal government is doing too little for key aspects of the environment, from protecting water or air quality to reducing the effects of climate change. And most believe the United States should focus on developing alternative sources of energy over expansion of fossil fuel sources, according to a new Pew Research Center survey.

A report from last year that focuses on the American public’s positions regarding climate change comes to the same conclusion. The project maps these attitudes across the US, tracing beliefs, risk perceptions, policy opinions, and everyday behaviors.

The US is not the only country to share this attitude; it seems to be the same globally: 75% of people in 19 countries view global climate change as a major threat (though, it’s not clear from the survey if these people also agree about the anthropogenic origin of climate change).

Meanwhile, extreme weather events translate to high costs:

In a new study, Stanford researchers report that intensifying precipitation contributed one-third of the financial costs of flooding in the United States over the past three decades, totaling almost $75 billion of the estimated $199 billion in flood damages from 1988 to 2017.

“The fact that extreme precipitation has been increasing and will likely increase in the future is well known, but what effect that has had on financial damages has been uncertain,” said lead author Frances Davenport, a PhD student in Earth system science at Stanford’s School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences (Stanford Earth). “Our analysis allows us to isolate how much of those changes in precipitation translate to changes in the cost of flooding, both now and in the future.”

oscillations that alter local astronomical tidal cycles and contribute to coastal impacts, will also increase in many regions. Here, we present an analysis of the CMIP5 climate model projections of future sea level to show that there is a tendency for a near-global increase in sea level variability with continued warming that is robust across models, regardless of whether ocean temperature variability increases. Specifically, for an upper-ocean warming by 2 °C, which is likely to be reached by the end of this century, sea level variability increases by 4 to 10% globally on seasonal-to-interannual timescales because of the nonlinear thermal expansion of seawater. As the oceans continue to warm, future ocean temperature oscillations will cause increasingly larger buoyancy-related sea level fluctuations that may alter coastal risks.

Who will pay for those damages? As I mentioned earlier (October 11, 2022), Florida is happy to get as much money as it can from the US federal government. Unfortunately, that is not an option for poor countries that don’t have such resources:

Twenty countries most vulnerable to climate change are considering halting their repayment of $685 billion in collective debt, loans that they say are an “injustice,” Mohamad Nasheed, the former president of the Maldives, said on Friday.

When the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund conclude their annual meetings in Washington on Sunday, Mr. Nasheed said he would tell officials that the nations were weighing whether to stop payments on their debts. The finance ministers are calling instead for a debt-for-nature swap, in which part of a nation’s debt is forgiven and invested in conservation.

“We are living not just on borrowed money but on borrowed time,” said Mr. Nasheed, who brought global attention to his sinking archipelago nation in the Indian Ocean by holding an underwater cabinet meeting in 2009. “We are under threat, and we should collectively find a way out of it.”

This fact sheet provides information on climate change polling in the United States and internationally from Spring 2015 to Spring 2016.

Poorer countries are trying to make the rich countries pay, arguing that rich countries have emitted the majority of the emissions responsible for climate change.

One rational attitude might be to leave the most vulnerable areas and look for safer places to live. In poor countries, this idea has resulted in a major increase in environmental refugees (put “environmental refugees” into the search box and see what you get).

In rich countries, such as the United States, however, the process seems to be going in reverse–in many cases, people are counterintuitively flocking to the most vulnerable places. Most of the fastest-growing states in the United States are in the West and South. In terms of the climate change impacts, the South is known for its floods and the West for its fires and droughts:

Nearly half of the continental United States is gripped by drought, government forecasters said Thursday, and conditions are expected to worsen this winter across much of the Southwest and South.

Mike Halpert, deputy director of the Climate Prediction Center, a part of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, said a lack of late-summer rain in the Southwest had expanded “extreme and exceptional” dry conditions from West Texas into Colorado and Utah, “with significant drought also prevailing westward through Nevada, Northern California and the Pacific Northwest.”

Much of the Western half of the country is now experiencing drought conditions and parts of the Ohio Valley and the Northeast are as well, Mr. Halpert said during a teleconference announcing NOAA’s weather outlook for this winter.

One big city will serve as an example:

The largest city in Arizona is its capital, Phoenix, which has been the fastest-growing city in the US for the last three years. It’s now (2022) the fifth most populated city in the US (after New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, and Houston).

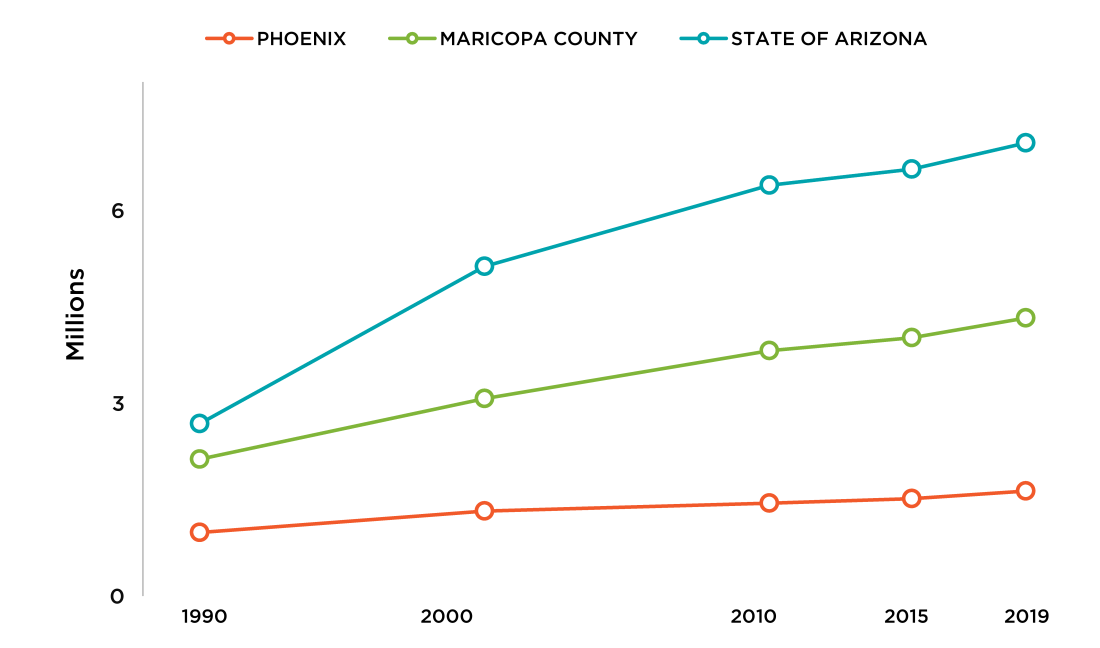

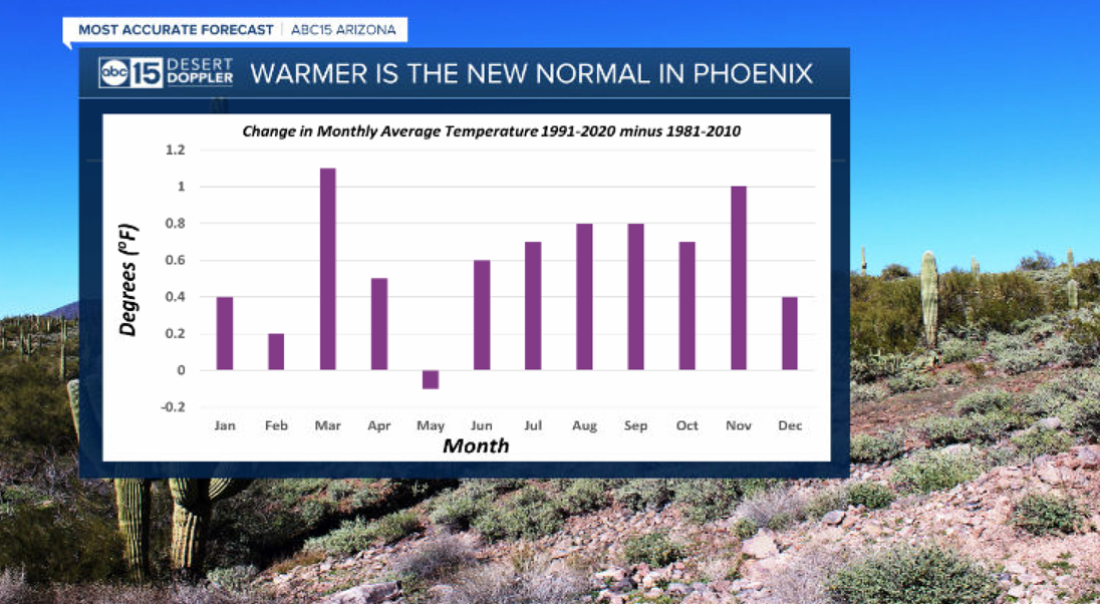

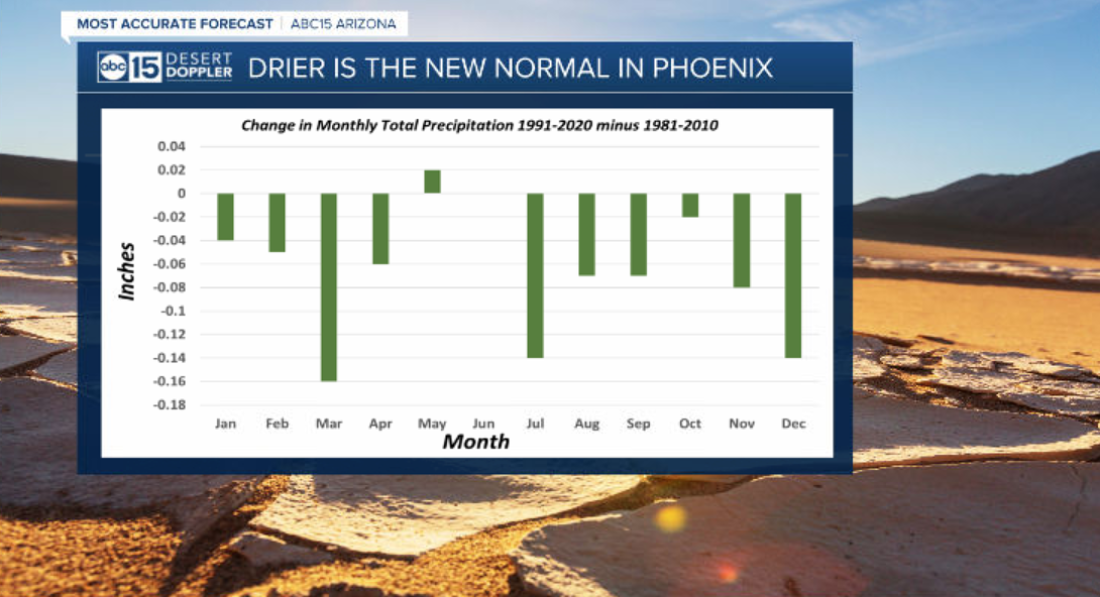

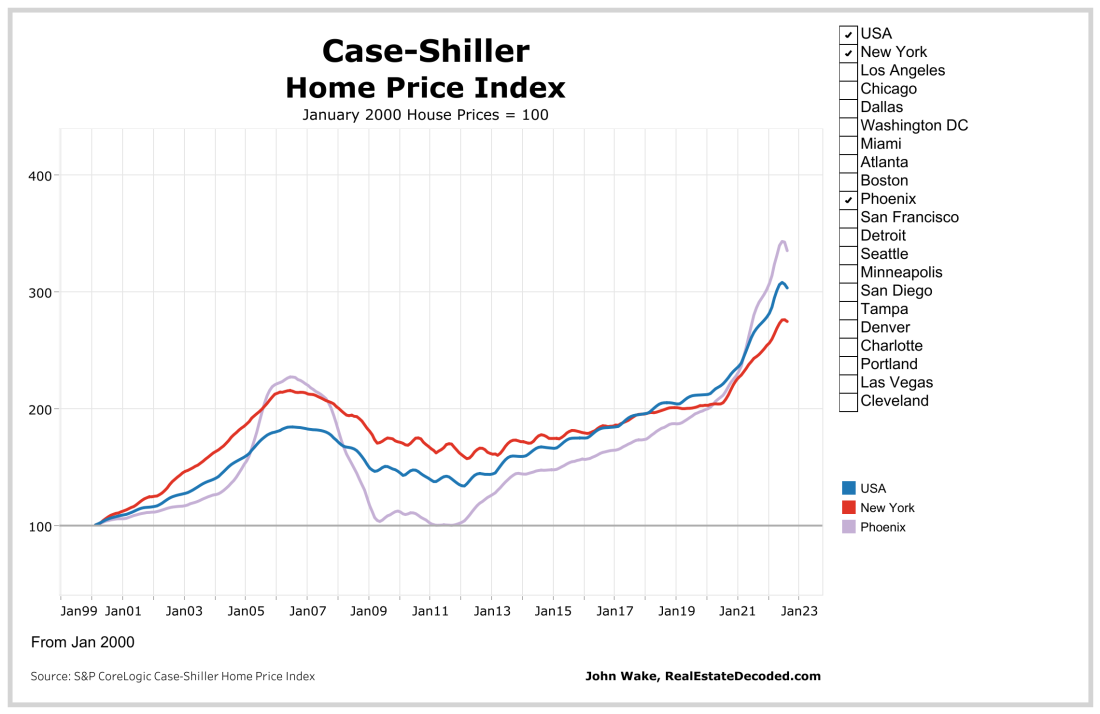

The four figures below show some of the changes in Phoenix over the last 30 years. These include population (Figure 1), climate—seen in terms of temperature (Figure 2) and precipitation (Figure 3), and the price of real estate (Figure 4) compared to New York City and the US average.

Figure 1 – Population increases in Arizona over the last 30 years (Source: City of Phoenix)

Figure 2 –Phoenix’s timeline of increased monthly average temperatures (Source: ABC 15 Arizona)

Figure 3 – Phoenix’s timeline of the decrease in precipitation (ex. January: -0.04” from 1991-2020)

Figure 4 – Case-Shiller home price index comparisons for the US, NYC, and Phoenix (Source: Arizona Real Estate Notebook)

Phoenix housing prices to be growing significantly faster than the national average. From the given data, Phoenix is about to resemble Dubai (See September 10, 2019 blog). The reasons for Arizona’s population growth are complex but proximity to California is playing an important role. Other, big, high-growth, states such as Florida and Texas are also suffering from major climate change impacts. The American public is not suicidal, but it seems to be discounting the problems visible within even a relatively short-term future in favor of present-day conveniences.

Part of me wants to criticize the people who complain that the government doesn’t do much in order to solve climate change when they themselves don’t do much either. Another part of me wants to counter that statement by saying that the government is one of the most powerful positions do solve something such as climate change, especially when compared to normal citizens who don’t have as much power or unity to change as much as they want.

I agree with Ashely that it’s interesting to find out that the “ Majorities of Americans say the federal government is doing too little for key aspects of the environment.” However, these individuals don’t do much themselves. Even if we were to blame the government for what they did, at times they won’t do anything about it. So, in order for things to change actions need to be taken.

“Poorer countries are trying to make the rich countries pay, arguing that rich countries have emitted the majority of the emissions responsible for climate change”.

I have to say that the rich countries have the money to pay the countries that are poor. With the rich countries paying the poor countries, they are benefiting from the money.

I find it funny how “ Majorities of Americans say the federal government is doing too little for key aspects of the environment” but these individuals themselves aren’t doing much of anything either. It’s not like things are going to change by blaming the government only because it’s not just the government that has to play a part but the citizens too. If we truly want things to change for the better EVERYONE has to play their part even if it’s taking small steps at first. Now poorer countries are making a sound argument that rich countries should step up to help these countries in need as they are majorly responsible ones for the consequences that we are experiencing due to climate change. I agree with their argument as rich counties do have the means to help others combat these disasters.

As an Arizonan, it’s alarming that Phoenix is growing so quickly. Not only are prices skyrocketing as Californians and others who see it as cheap come in and buy everything up, but we literally don’t have enough water for all these people!