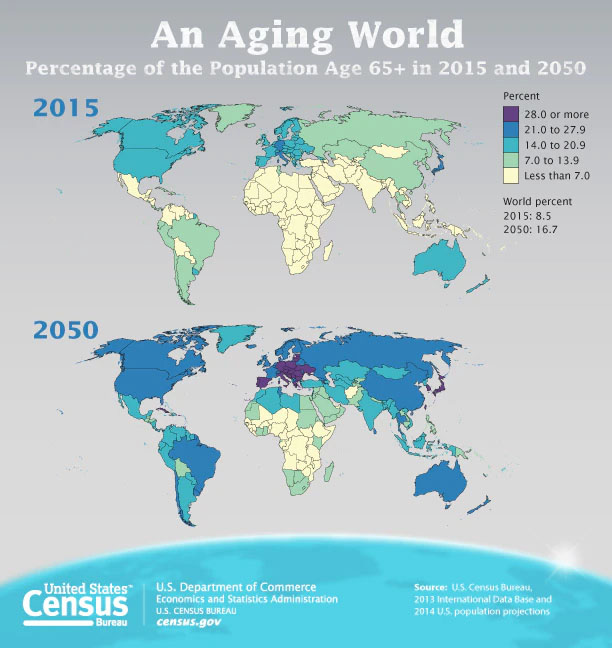

Last week’s blog focused on the dynamics of global population changes, which are determined by the balance of births and deaths. The global population is still growing because births are still outpacing deaths but the near-term (one-generation) trends predict a coming reversal when the global population will reach a maximum beyond which it will start to shrink. An important impact of these changes is the global increase in median age: the world is aging. However, the timing of these global trends is not universal. Figure 1 shows the present distribution of older people (>65) in 2015 with its projections in the near future (2050).

Figure 1 – Percentage of elderly by country (Source: US Census)

Figure 1 – Percentage of elderly by country (Source: US Census)

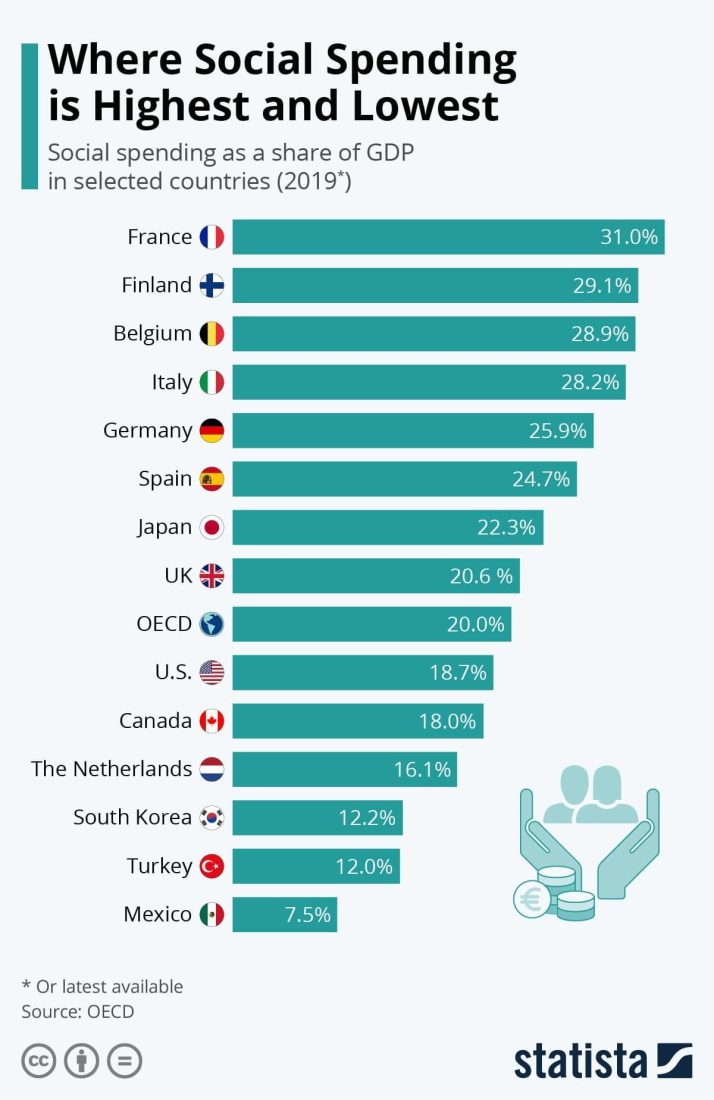

An aging, shrinking world requires overcoming shrinking economic activity that often scales with population and increase in social spending. The OECD list of social spending by (mostly) developed countries is shown in Figure 2. It is a substantial fraction of these countries’ GDP. That fraction increases with the aging of the population.

Below is a list of three major countries that are experiencing these trends and some steps that they are trying to take to mitigate the situation. I will expand the list in next week’s blog, where I will put the emphasis on immigration:

France

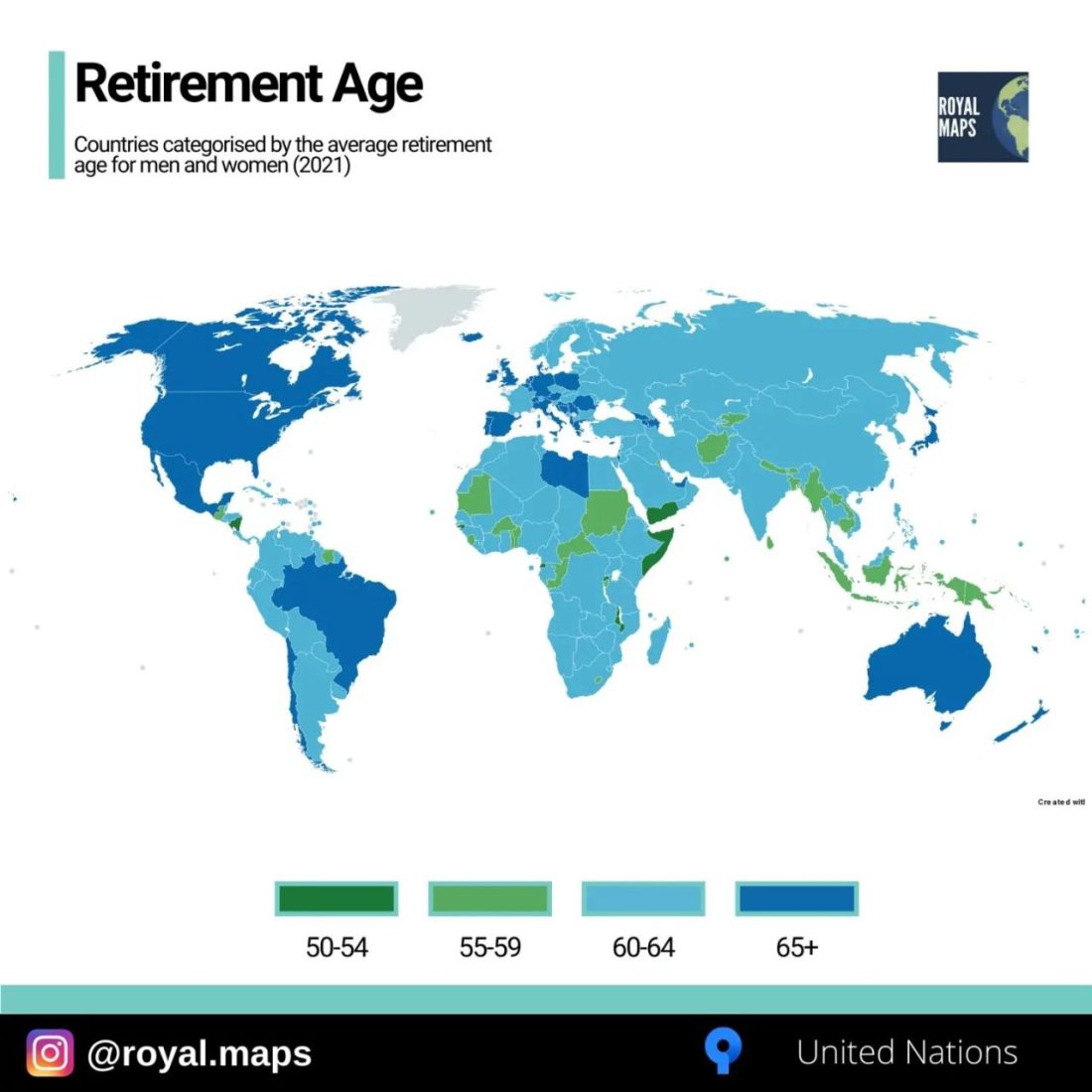

Figure 1 shows that France is not in the worst position in terms of the aging of its population, but Figure 2 shows that it is at the top of the list in terms of social spending. Figure 3 shows that it has one of the lowest retirement ages in Europe (Ukraine and Russia have traditionally had lower retirement ages but we have yet to see how these will change after the war). Yet, the French government is now proposing to remedy this situation by raising the retirement age from 62 to 64. Major demonstrations are now taking place to block this “major” adjustment:

PARIS, Feb 7 [2023] (Reuters) – Public transport, schools and refinery supplies in France were disrupted on Tuesday as trade unions led a third wave of nationwide strikes against President Emmanuel Macron’s plans to make the French work longer before retirement.

Tuesday’s multi-sector walkouts come a day after pension reform legislation began its bumpy passage through parliament and are a test of Macron’s ability to enact change without a working majority in the National Assembly.

The government says people must work two years longer – meaning for most until the age of 64 – in order to keep the budget of one of the industrial world’s most generous pension systems in the black.

The French spend the largest number of years in retirement among OECD countries – a deeply cherished benefit that a substantial majority are reluctant to give up, polls show.

The French love to demonstrate; we will see how this will play out.

Figure 2 – Social spending by country (source: Statista via World Economic Forum)

Figure 3 – Retirement age by country (Source: Royal Maps via Maps on the Web)

South Korea

South Korea is among the record holders, in terms of both shrinking and aging population:

South Korea’s statistics agency announced in September that the total fertility rate — the average number of babies born to each woman in their reproductive years — was 0.81 last year. That’s the world’s lowest for the third consecutive year.

The population shrank for the first time in 2021, stoking worry that a declining population could severely damage the economy — the world’s 10th largest — because of labor shortages and greater welfare spending as the number of older people increases and the number of taxpayers shrinks.

Many young South Koreans say that, unlike their parents and grandparents, they don’t feel an obligation to have a family. They cite the uncertainty of a bleak job market, expensive housing, gender and social inequality, low levels of social mobility and the huge expense of raising children in a brutally competitive society. Women also complain of a persistent patriarchal culture that forces them to do much of the childcare while enduring discrimination at work.

Russia

Russia is now at the center of the news because of its invasion of Ukraine but its decline in its population started way before that:

Crippling disruptions from the war are converging with a population crisis rooted in the 1990s, a period of economic hardship after the Soviet breakup that sent fertility rates plunging. Independent demographer Alexei Raksha is calling it “a perfect storm.”

As mentioned above, the decline in the Russian population started with the breakup of the Soviet Union in 1990. The government started experimenting with various payments to encourage families to have children, and has continued the policy. More recent promises came out to a few thousand dollars. President Putin came to power in 2000. I traveled to Russia in 2006. Part of the itinerary was to take a river cruise from St. Petersburg to Moscow. Many of our guides on the cruise were young Russian ladies. I asked some of them if the incentives offered by the president would encourage them to have children. They laughed and said that if President Putin promised them an apartment, they would start a conversation.

In next week’s blog, I will discuss a new angle on this topic that has emerged since the Russian invasion of Ukraine.