By the time that you read this blog (and the next two), I will be in Australia. I will return toward the end of the month, and I will write about some of my experiences. In this blog and with the one that will follow, I will abandon my dark glasses from the last blog and focus on places that are trying to make our life brighter. I am starting with Arizona.

Arizona has been in the news often recently, and not always for the better. Its place in the news is often dominated by two issues: politics and the impact of climate change. The latter focuses especially on rising temperatures and water stress. I am following the daily temperature in the two biggest cities: Phoenix and Tucson. Starting in mid-May, when almost everywhere else in the US was still experiencing spring, the temperature there already hovered around 100oF. It is predicted to go considerably higher this summer, in part due to El Niño’s impact. Toward the end of May, a research article came out in the Journal of Environmental Science and Technology titled, “How Blackouts during Heat Waves Amplify Mortality and Morbidity Risk,” written by 14 coauthors, with Brian Stone Jr. as the corresponding author. The abstract is cited below:

The recent concurrence of electrical grid failure events in time with extreme temperatures is compounding the population health risks of extreme weather episodes. Here, we combine simulated heat exposure data during historical heat wave events in three large U.S. cities to assess the degree to which heat-related mortality and morbidity change in response to a concurrent electrical grid failure event. We develop a novel approach to estimating individually experienced temperature to approximate how personal-level heat exposure changes on an hourly basis, accounting for both outdoor and building-interior exposures. We find the concurrence of a multiday blackout event with heat wave conditions to more than double the estimated rate of heat-related mortality across all three cities, and to require medical attention for between 3% (Atlanta) and more than 50% (Phoenix) of the total urban population in present and future time periods. Our results highlight the need for enhanced electrical grid resilience and support a more spatially expansive use of tree canopy and high albedo roofing materials to lessen heat exposures during compound climate and infrastructure failure events.

Phoenix’s population is now estimated to be 1.6 million and it is the fastest-growing city in the US. Counting the entire Phoenix-Mesa-Scottsdale metropolitan area, that number is almost 5 million. One of the conclusions of this article is that in case of a heat wave with power failure, 50% of the population would require medical care – that’s 800,000 people (or 2.5 million in the Phoenix metro area)! This is serious. As we can see below, the water availability cannot keep up with the growth:

Underground storage may be a key for Western states navigating water shortages and extreme weather. Aquifers under the ground have served as a reliable source of water for years. During rainy years, the aquifers would fill up naturally, helping areas get by in the dry years. But growing demand for water coupled with climate change has resulted in shortages as states pump out water from aquifers faster than they can be replenished. The fallout can also lead to damaged vegetation and wildlife as streams run dry and damage to aqueducts and flood control structures from sinking land. Municipalities and researchers across the country are working on ways to more efficiently replenish emptied-out aquifers. By over pumping aquifers “you’ve created space. There’s space under the ground that used to be filled with water,” explained Michael Kiparsky, water program director at the Center for Law, Energy & the Environment at the University of California, Berkeley School of Law. “And what we can do with these groundwater recharge projects is take advantage of that space, which is vastly greater than the sum of all of the surface storage reservoirs that exist now or could be built,” he said. Several communities across California, Arizona and other states have been using managed aquifer recharge for years to better regulate local water supplies. If implemented on a wide enough scale, recharge projects hold the potential to bolster water security in drought-stricken regions while improving the health of the environment. Kiparsky said if it can be pulled off, “it holds the promise of being able to generate a whole new water supply we really didn’t even know that we had.”

Water stress is a serious issue. I wrote about it in previous blogs (See “Human Reaction to Climate Shift” from November 1, 2022, and “Adaptation and Affordability” from December 6, 2022). As I said then:

In rich countries, such as the United States …in many cases, people are counterintuitively flocking to the most vulnerable places. Most of the fastest-growing states in the United States are in the West and South. In terms of the climate change impacts, the South is known for its floods and the West for its fires and droughts…

Now, Arizona seems to have done a U-turn and is trying to limit construction in certain areas to try to match growth with available water supply:

As the mayor of an old farming town bursting with new homes, factories and warehouses, Eric Orsborn spends his days thinking about water. The lifeblood for this growth is billions of gallons of water pumped from the ground, and his city, Buckeye, Ariz., is thirsty for more as builders push deeper into the desert fringes of Phoenix.

But last week, Arizona announced it would limit some future home construction in Buckeye and other places because of a shortfall in groundwater. The worried calls started pouring in to Mr. Orsborn.

“I have neighbors who come up to me and say, ‘What are you doing? Are we running out of water?’” Mr. Orsborn said. “It put our community on edge, thinking, ‘What is going on here and do I need to move?’”

No, he tells them. Breathe.

The upheaval was caused by a new state study that found groundwater supplies in the Phoenix area were about 4 percent short of what is needed for planned growth over the next 100 years. That may feel like a far-off horizon, but it is enough of a change to force the state to rethink its future in the near and long terms.

Arizona has some of the strictest groundwater laws in the country in more regulated areas like Phoenix. For decades, the state has required new developments to show they have a 100-year supply of water before they can sell lots or break ground.

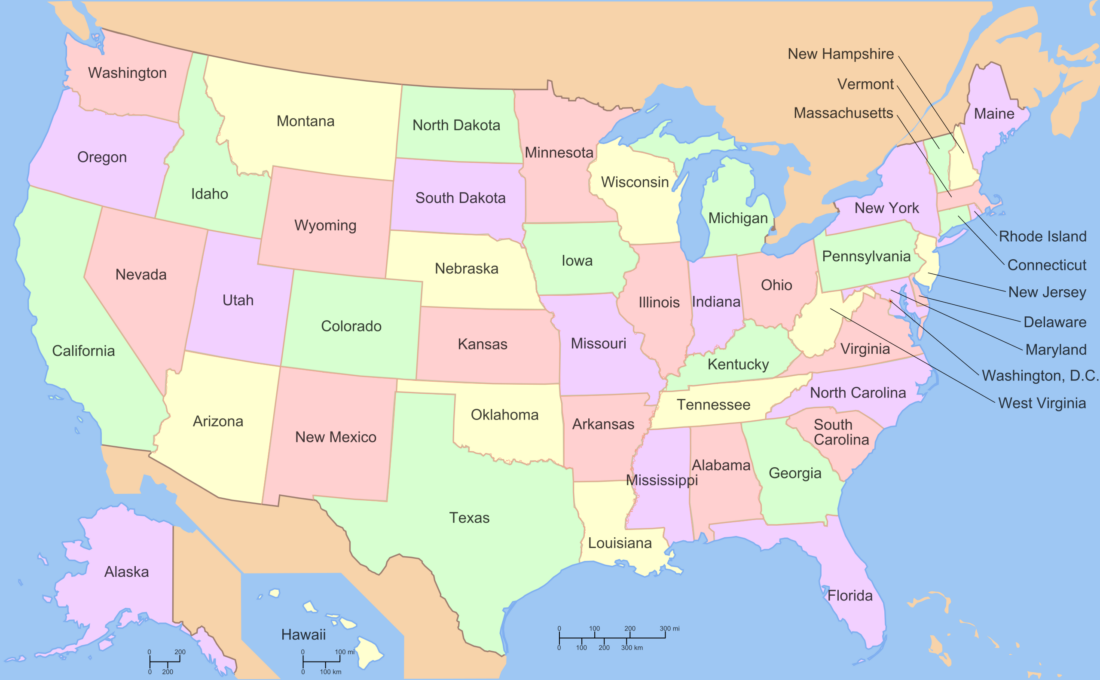

Arizona is also trying to increase its water supply by using desalination. However, a quick look at the map below shows that Arizona doesn’t have access to the ocean. What it has is a border with California, which has a long ocean shore. However, California, for a variety of reasons, also has massive water stress. For a long time, the state has been considering constructing water desalination systems. I wrote about it 10 years ago (See the November 12, November 19, and December 3, 2013 blogs). The feedback on my writing by a Californian expert on the water issue (Peter Gleick) can be found in the November 19, 2013 blog.

(Source: Wikimedia SVG map of the United States, Created by Wapcaplet)

I tried to get more recent information on desalination efforts in California and ended up with one company:

Environmentalists say desalination decimates ocean life, costs too much money and energy, and soon will be made obsolete by water recycling. But as Western states face an epic drought, regulators appear ready to approve a desalination plant in Huntington Beach, California.

After spending 22 years and $100 million navigating a thicket of state regulations and environmentalists’ challenges, Poseidon Water is down to one major regulatory hurdle – the California Coastal Commission. The company feels confident enough to talk of breaking ground by the end of next year on the $1.4 billion plant that would produce some 50 million gallons of drinking water daily.

Arizona was apparently familiar with desalination efforts in California and decided to try to build its own facility in Mexico:

Fifty miles south of the U.S. border, at the edge of a city on the Gulf of California, a few acres of dusty shrubs could determine the future of Arizona.

As the state’s two major sources of water, groundwater and the Colorado River, dwindle from drought, climate change and overuse, officials are considering a hydrological Hail Mary: the construction of a plant in Mexico to suck salt out of seawater, then pipe that water hundreds of miles, much of it uphill, to Phoenix.

The idea of building a desalination plant in Mexico has been discussed in Arizona for years. But now, a $5 billion project proposed by an Israeli company is under serious consideration, an indication of how worries about water shortages are rattling policymakers in Arizona and across the American West.

The pipeline is proposed to move desalinated water from Mexico to Phoenix. There is a strong likelihood of it passing close to Tucson. Tucson is the second largest city in Arizona; its present rate of growth is considerably slower than that of Phoenix. However, most of the water-related policies are decided at the state level. We are fortunate to have a friend in Tucson: Sonya Landau, the editor of this blog (see her guest blogs from June 22, 2021 and October 9, 2018). It will be fascinating to see her take on Arizona’s fight between water and growth in next week’s guest blog.

I like it when folks come together and share views.

Great website, stick with it!

I’ve never experienced a water shortage first hand where I live, but, over the summer I was able to see some of dynamics of how one was treated when I visited my sister in California. In the hotels, they all had signs asking to reuse towels so they don’t have to wash them as much and waste water and my sister and everyone she lived with used as little water as possible— when we stayed over they asked us to not stay in the shower longer than five minutes, and my sister scolded me if I kept the sink on while using the soap. I think it is worth noting that there is community and individual effort and want to mitigate crisis like these for the sake of the community.