The New York Times recently reported (June 20, 2013) that shortly, President Obama would announce a new set of initiatives to combat climate change, and that he will make it a major focus to fight climate change during his second term. Since this blog will be posted while I am in Africa, it is very likely that this initiative will be announced before the blog is posted. The president is now well aware that he cannot pass a major climate change initiative through the present congress. So the thinking is that the initiative will strongly rely on executive power — mainly through the regulatory powers of the EPA (Environmental Protection Agency). I am proposing a timely change in accounting that, while it does not immediately seem directly related to any executive attempt to limit greenhouse emissions, could potentially make for a big change in the political terrain of this issue.

Recently a new term has popped up in the debate on climate change: “unburnable fuels.”

The term probably got its start in a research article in Nature (Nature 458, 1158-1162 (30 April 2009)), titled, “Greenhouse-gas emission targets for limiting global warming to 2 °C.” It starts with the following paragraph:

More than 100 countries have adopted a global warming limit of 2°C or below (relative to preindustrial levels) as a guiding principle for mitigation efforts to reduce climate change risks, impacts and damages 1, 2. However, the greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions corresponding to a specified maximum warming are poorly known owing to uncertainties in the carbon cycle and the climate response. Here we provide a comprehensive probabilistic analysis aimed at quantifying GHG emission budgets for the 2000–50 period that would limit warming throughout the twenty-first century to below 2°C, based on a combination of published distributions of climate system properties and observational constraints.

The authors summarized the quantitative conclusion to this challenge:

For our illustrative distribution of climate system properties, we find that the probability of exceeding 2°C can be limited to below 25% (50%) by keeping 2000–49 cumulative CO2 emissions from fossil sources and land use change to below 1,000 (1,440) Gt CO2 (Fig. 3a and Table 1). If we resample model parameters to reproduce 18 published climate sensitivity distributions, we find a 10–42% probability of exceeding 2°C for such a budget of 1,000Gt CO2. If the acceptable exceedance probability were only 20%, this would require an emission budget of 890 Gt CO2 or lower (illustrative default). Given that around 234 Gt CO2 were emitted between 2000 and 2006 and assuming constant rates of 36.3 Gt CO2 yr-1 (ref. 3) thereafter, we would exhaust the CO2 emission budget by 2024, 2027 or 2039, depending on the probability accepted for exceeding 2°C (respectively 20%, 25% or 50%).

The issue was dormant for a few years, until very recently the number 1,000Gt (1GT = 1 billion tons) of carbon dioxide started to attract attention in print, lecture circuits and the blogosphere.

The Economist published (May 4th 2013 issue) a short article, “Either governments are not serious about climate change or fossil-fuel firms are overvalued.” The article starts with the following paragraph:

Markets can misprice risk, as investors in subprime mortgages discovered in 2008. Several recent reports suggest that markets are now overlooking the risk of “unburnable carbon”. The share prices of oil, gas and coal companies depend in part on their reserves. The more fossil fuels a firm has underground, the more valuable its shares. But what if some of those reserves can never be dug up and burned?

It summarizes the present situation this way:

If governments were determined to implement their climate policies, a lot of that carbon would have to be left in the ground, says Carbon Tracker, a non-profit organization, and the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change, part of the London School of Economics. Their analysis starts by estimating the amount of carbon dioxide that could be put into the atmosphere if global temperatures are not to rise by more than 2°C, the most that climate scientists deem prudent. The maximum, says the report, is about 1,000 gigatons (GTCO2)between now and 2050. The report calls this the world’s “carbon budget”.

Existing fossil-fuel reserves already contain far more carbon than that. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA),in its “World Energy Outlook”, total proven international reserves contain 2,860GTCO2—almost three times the carbon budget.The report refers to the excess as “unburnable carbon”. Most of the reserves are owned by governments or state energy firms; they could be left in the ground by public-policy choice (ie, if governments took the 2°C target seriously). But the reserves of listed oil companies are different. These are assets developed using money raised from investors who expect are turn. Proven reserves of listed firms contain 762GTCO2—most of what can prudently be burned before 2050. Listed potential reserves have 1,541GTCO2 embedded in them.

The conclusion is that to satisfy the estimated below 2°C target, much of the “proven” reserves will have to stay forever in the ground as untapped, unburnable fuel.

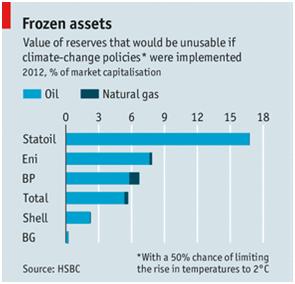

The distribution of this unburnable fuel among the oil company was given by the Economist and is shown below:

How the oil and gas reserves became part of market capitalization is a complex issue, so here are some of the relevant paragraphs of the Wikipedia summary to get you up to speed:

Proven reserves are those reserves claimed to have a reasonable certainty (normally at least 90% confidence) of being recoverable under existing economic and political conditions, with existing technology. Industry specialists refer to this as P90 (i.e., having a 90% certainty of being produced). Proven reserves are also known in the industry as 1P. [8][9]

Proven reserves are further subdivided into “proven developed” (PD) and “proven undeveloped”(PUD).[9][10] PD reserves are reserves that can be produced with existing wells and perforations, or from additional reservoirs where minimal additional investment (operating expense) is required.[10]PUD reserves require additional capital investment (e.g., drilling new wells) to bring the oil to the surface .[8][10]

Until December 2009 “1P” proven reserves were the only type the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission allowed oil companies to report to investors. Companies listed on U.S. stock exchanges must substantiate their claims, but many governments and national oil companies do not disclose verifying data to support their claims. Since January 2010 the SEC now allows companies to also provide additional optional information declaring “2P” (both proven and probable) and “3P” (proven +probable + possible) provided the evaluation is verified by qualified third party consultants, though many companies choose to use 2P and 3P estimates only for internal purposes.

Much of the political opposition (at least in the US) to mitigation efforts to counter human contributions to climate change, comes from the “Heartland Institute” and its supporters. There is a short description on Wikipedia that focuses on the financing behind the institute. The relevant part to the present issue is as follows:

Oil and gas companies have contributed to the Heartland Institute, including over $600,000 from ExxonMobil between 1998 and 2005.[43 ] Greenpeace reported that Heartland received almost $800,000 from ExxonMobil.[20] In 2008, ExxonMobil said that they would stop funding to groups skeptical of climate warming, including Heartland.[43][44][45] Joseph Bast, president of the Heartland Institute, argued that ExxonMobil was simply distancing itself from Heartland out of concern for its public image.[43]

The last series of blogs have focused, among other things, on the quote from ExxonMobil CEO, Rex Tillerson, who reputedly said, “What good is it to save the planet if humanity suffers?” – equating inherent “suffering” with a more limited use of fossil fuels. What he actually means by this is that setting a “cap” of usage at below the total quantity of “proven reserves” that still lay untapped would mean a major reduction in the capitalization rates of ExxonMobil and other oil companies (which would, in turn, require realignment of the stock prices). So from this perspective, the introduction of a “cap” would mean major confiscation of capital from the stock holders – an action that is viewed by many as un-American.

The Security and Exchange Commission (SEC) made an administrative decision to categorize untapped oil reserves as part of the capital value of a company, for accounting purposes; this decision can be reversed through an administrative order. In reality, these reserves are no more capital than would be the “good ideas” of the company’s staff scientists. They contribute to the capitalization process through good name, track records, etc., but do not add to the explicit pricing or marketability of the good idea. If the accounting rules were changed, so as to remove those reserves from the capitalization appraisal, the company would still retain the ownership and exploration rights of the real-estate in which the reserves are buried, but the reserves would only factor into the capitalization when they were ready to be marketed. The assessment of the value of this real estate would, instead, follow the same objective procedures that other commercial real estate properties enjoy. Once we put a “cap” on extraction, if the market were to exceed this “cap,” the price of the real estate would rise, thus benefiting the company, and rendering moot the need to use its resources to oppose the “cap.” This is an example of a situation where a change in the status quo could potentially benefit almost all parties.

Obamacare is great all around and his views on climate change issue are also good. Excellent posting, I am always salute such type of great stuff.

In my own opinion, I think Obama has made a good decision to prioritize the climate change issues. Hope that this issue will be resolved soon.

Hello everyone. The European union is doing qyuue great achievements in terms of energy saving and use of renewable products. Here in Spain recyclable bags are used not to damage Mother Nature

regards

Joe Diaz

Hello everyone. Regarding climate change of the earth, we all know that we achieve energy savings as well as savings in heat sources such as lamps incandesentes we must use new technologies such as LED lamps, which do not generate heat , limpa emit light, and they last a long time.

regards

Jose Guerra