(Source)

I will start with the big picture: “The US government has declared war on the very idea of climate change” focused on the EPA (Environmental Protection Agency):

Americans are used to whiplash in their climate policy. The US has been in and out and in and out again of the key Paris climate agreement over the past four presidencies.

But in his second administration, President Donald Trump is not just approaching climate science with skepticism. Instead, his administration is moving to destroy the methods by which his or any future administration can respond to climate change.

These moves, which are sure to be challenged in court, extend far beyond Trump’s well-documented antipathy toward solar and wind energy and his pledges to drill ever more oil even though the US is already the world’s largest oil producer.

A similar perspective, with a bit more history, from the NYT:

Ever since 1965, when President Lyndon B. Johnson’s science advisory committee warned of the dangers of unchecked global warming, the United States has taken steps to protect people from these risks.

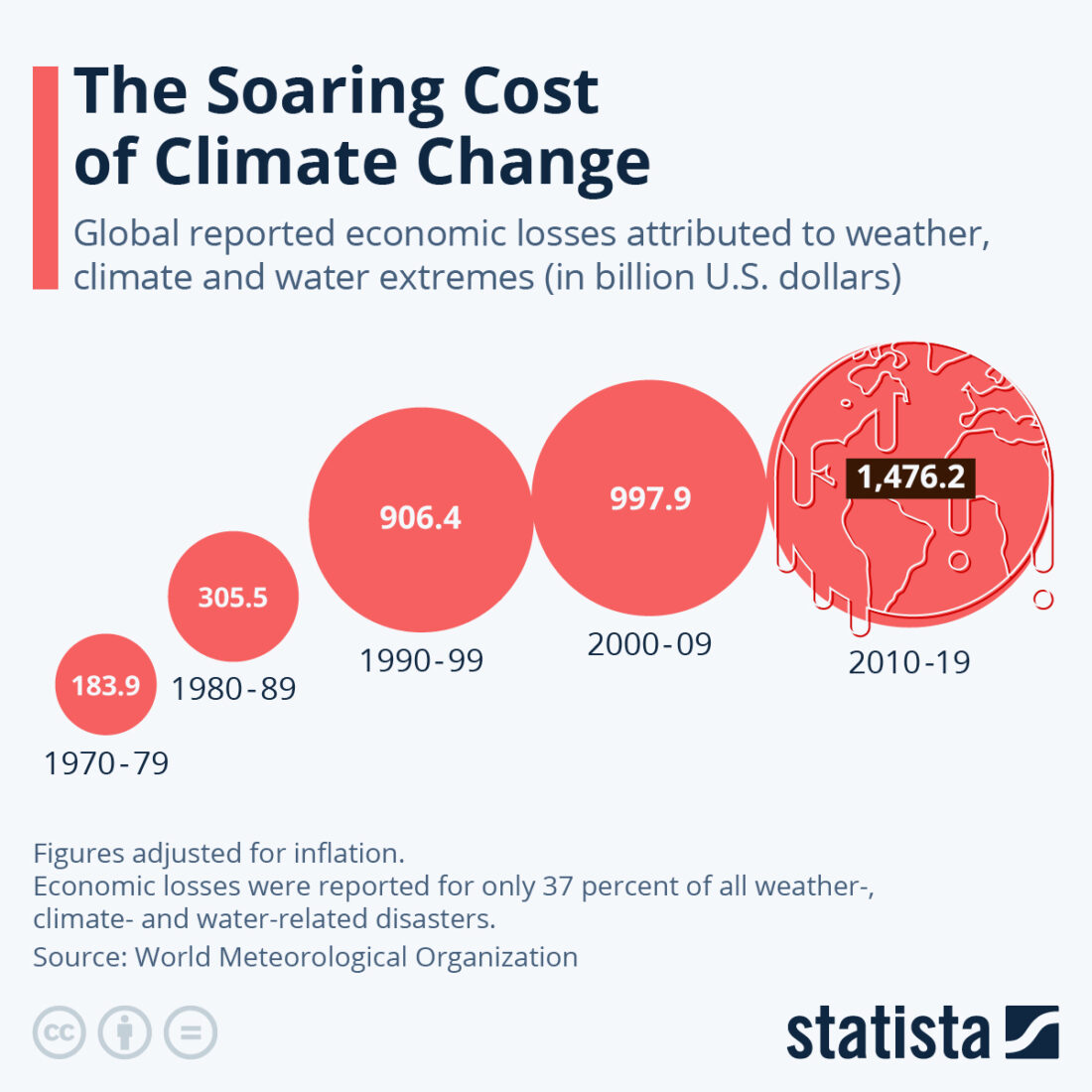

Now, however, the Trump administration appears to be essentially abandoning this principle, claiming that the costs of addressing climate change outweigh the benefits. The effect is to shift more of the risk and responsibility onto states and, ultimately, individual Americans, even as rising temperatures fuel more extreme and costly weather disasters nationwide, experts say.

“It’s a radical transformation of government’s role, in terms of its intervention into the economy to try to promote the health and safety of citizens,” said Donald Kettl, a professor emeritus at the University of Maryland’s School of Public Policy.

Direct target for this attitude is redirecting the agency that is supposed to provide direct assistance to states that suffer the impacts of major losses, FEMA (Federal Emergency Management Agency). Below is how AI (through Google) describes what FEMA does:

FEMA, or the Federal Emergency Management Agency, is a U.S. government agency that supports citizens and first responders by preparing for, protecting against, responding to, recovering from, and mitigating all hazards. It provides financial and technical assistance to individuals and communities after disasters, offers guidance on flood insurance and risk reduction, and supports programs that help people and organizations recover and rebuild.

The sad part is that FEMA is being redirected toward blocking immigration, much of which is accelerated from the impacts of global threats on the rest of the world. I discussed this topic in a previous blog (January 16, 2024), before the results of the 2024 elections were known.

Here is what the present Trump administration is trying to do to FEMA:

WASHINGTON, July 25 (Reuters) – The Federal Emergency Management Agency is preparing to send $608 million to states to construct immigrant detention centers as part of the Trump administration’s push to expand capacity to hold migrants.

FEMA is starting a “detention support grant program” to cover the cost of states building temporary facilities, according to an agency announcement, opens new tab. States have until August 8 to apply for the funds, according to the post.

The threat is provoking a response that reminds us all of a previous response where FEMA didn’t do a great job, almost 20 years ago to the day:

Employees at the Federal Emergency Management Agency wrote to Congress on Monday warning that the Trump administration had reversed much of the progress made in disaster response and recovery since Hurricane Katrina pummeled the Gulf Coast two decades ago.

The letter to Congress, titled the “Katrina Declaration,” rebuked President Trump’s plan to drastically scale down FEMA and shift more responsibility for disaster response — and more costs — to the states. It came days before the 20th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina, one of the deadliest and costliest storms to ever strike the United States.

This adversarial response is not limited to FEMA. The federal government department with the central responsibility for mitigating climate change by replacing the reliability on fossil fuels that are at the center of the anthropogenic impact on the climate, carbon dioxide, is the Department of Energy. Below is what the new head of the department is now doing… (Energy chief suggests Trump administration is altering previously published climate reports | CNN):

Energy Sec. Chris Wright said Tuesday night the Trump administration is updating the National Climate Assessments that have been previously published, which the administration recently removed from government websites.

…with the following result: (https://www.energy.gov/sites/default/files/2025-07/DOE_Critical_Review_of_Impacts_of_GHG_Emissions_on_the_US_Climate_July_2025.pdf):

Over my lifetime, I’ve had the privilege of working as an energy entrepreneur across a range of fields—nuclear, geothermal, natural gas, and more—and I now serve as Secretary of Energy under President Donald Trump. But above all, I’m a physical scientist who sees modern energy as nothing short of miraculous. It powers every aspect of modern life, drives every industry, and has made America an energy powerhouse with the ability to fuel global progress. The rise of human flourishing over the past two centuries is a story worth celebrating. Yet we are told—relentlessly—that the very energy systems that enabled this progress now pose an existential threat. Hydrocarbon-based fuels, the argument goes, must be rapidly abandoned or else we risk planetary ruin. That view demands scrutiny. That’s why I commissioned this report: to encourage a more thoughtful and science-based conversation about climate change and energy. With my technical background, I’ve reviewed reports from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the U.S. government’s assessments, and the academic literature. I’ve also engaged with many climate scientists, including the authors of this report. What I’ve found is that media coverage often distorts the science. Many people walk away with a view of climate change that is exaggerated or incomplete. To provide clarity and balance, I asked a diverse team of independent experts to critically review the current state of climate science, with a focus on how it relates to the United States.

The adversarial response penetrates directly to the data collection, disabling preparation for effective mitigation. There is some counteracting effort to shift reliance of data collection to the private sector. (Private Companies Step up to Gather Weather Data for NOAA as Staffing Cuts Hobble Agency Forecasting – Inside Climate News):

As the beleaguered weather service struggles to maintain its forecasting and other services, it’s leaning on private companies to pick up the slack. For example, WindBorne, which is backed by Khosla Ventures, a venture capital firm focused on investing in companies with innovative business models and technologies, is opening five new balloon launch sites in the U.S. this year as it expands its work with the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the parent agency of the NWS.

The impacts on health are early signs of the threats and are being reevaluated. (National Academies Launch Fast-Track Review of Latest Evidence for Whether Greenhouse Gas Emissions Endanger Public Health and Welfare | National Academies):

WASHINGTON — A new National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine study will review the latest scientific evidence on whether greenhouse gas emissions are reasonably anticipated to endanger public health and welfare in the U.S.

The committee conducting the study will focus on evidence gathered by the scientific community since 2009 — when the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency first declared greenhouse gas emissions a danger to public health. Any conclusions in the committee’s report will describe supporting evidence, the level of confidence in a conclusion, and areas of disagreement or unknowns.

The EPA recently announced that it intends to rescind its “endangerment finding,” a statement issued by the agency in 2009 that found that greenhouse gas emissions do pose risks to public health and welfare. The National Academies study will be completed and publicly released in September, in time to inform EPA’s decision process.

“It is critical that federal policymaking is informed by the best available scientific evidence,” said Marcia McNutt, president of the National Academy of Sciences. “Decades of climate research and data have yielded expanded understanding of how greenhouse gases affect the climate. We are undertaking this fresh examination of the latest climate science in order to provide the most up-to-date assessment to policymakers and the public.”

The annual gatherings of the Conference of the Parties (COP) serve as a governing body to assess progress on climate goals, negotiate agreements, and drive collaborative climate action among almost every country in the world. This year the COP meeting is supposed to take place in Belem, Brazil on November 10th. To those of you who have no idea where Belem is, you’d better check the map. It is one of the largest cities in the Brazilian Amazon, with a population of about 1 million inhabitants. The US, once a major participant in these meetings (put COP into the search box to follow previous entries), is expected to be seriously underrepresented:

The Trump administration fired the last of the US climate negotiators earlier this month, helping cement America’s withdrawal from international climate diplomacy. It may also have handed a huge victory to China.

The elimination of the State Department’s Office of Global Change — which represents the United States in climate change negotiations between countries — leaves the world’s largest historical polluter with no official presence at one of the most consequential climate summits in a decade: COP30, the annual UN climate talks in Belém, Brazil, in November.

Without State’s climate staff in place, even Capitol Hill lawmakers who usually attend the summits have been unable to get accredited, a source familiar with the process said.

The courts are not providing much help with the broad changes that the administration is now instituting.The US can’t attempt to mitigate future threats without an agreement or even discussions by Congress:

Sept 2 (Reuters) – President Donald Trump’s administration can proceed with terminating more than $16 billion in grants awarded to non-profit groups to fight climate change, a U.S. federal appeals court ruled on Tuesday.

Trump’s predecessor Joe Biden’s signature 2022 Inflation Reduction Act had awarded the grants aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions. The Environmental Protection Agency under Trump had sought to terminate the grants.

Next week’s blog will try to address the role of science in trying to predict future global threat developments and how the present US administration is trying to decapacitate this tool.

Figure 1 – Diving in the Great Barrier Reef more than a generation ago (I was 60, my wife 50+)

Figure 1 – Diving in the Great Barrier Reef more than a generation ago (I was 60, my wife 50+) Figure 2 – Bleached coral in the Great Barrier Reef

Figure 2 – Bleached coral in the Great Barrier Reef Figure 3 – Bleached coral in Belize (photographed by my wife and me in 2003)

Figure 3 – Bleached coral in Belize (photographed by my wife and me in 2003) A young visitor at the Peace Memorial Park in Hiroshima

A young visitor at the Peace Memorial Park in Hiroshima

(Source:

(Source: