Recently, I have been writing a lot about water- I feel honored that one of the local papers here in Brooklyn, Our Time Press, picked up one of my posts in its entirety to republish. I am trying to get my ideas out into the world, and it is gratifying to know that some people are listening.

In previous blogs (August 27, September 3 and September 10), I have made the case that Earth is not dealing with water shortage, but rather with water stress. Given that 70% of the planet’s surface is covered with deep oceans, and that the global water cycle accounts for the water’s flow through land, sea and the atmosphere, we will not have an actual shortage of water so long as the planet remains a habitable environment. On the other hand, there is a serious water stress that results from the imbalance between supply and demand of fresh water. My September 10 blog focused on one way of trying to alleviate the stress in fresh water: recycling used water, thus forming a smaller, separate fresh water cycle within the global one.

In this and the next blog, I will explore the “classic” economics of dealing with imbalances between supply and demand. This blog focuses on the demand side. Economists tell us that there are two conventional ways to reduce demand of any commodity: either use less or find alternative commodities that will function in a similar way. Unfortunately, water is distinct from other commodities on two levels. First, both physics and biology tell us that liquid water is unique in its ability to support life – no substitutions are possible. Additionally, the adequate availability of fresh water is now being regarded as an element of international human rights law.

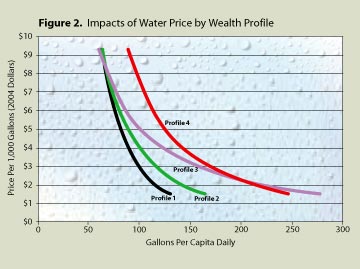

Like any other commodity, there is no question that if we raise the price of water we will reduce consumption. The figure below, taken from a study on the effects of water pricing and wealth profiles on water use demonstrates the impact clearly.

The study was carried out by four Florida water management districts. The decline in use shown with the increased price is general. The price-induced changes in water consumption vary according to the property value. Profile 1 represents the properties with the lowest assessed values, while profile 4 shows those with the highest. It is clear from the graph that the properties with the highest assessed values had the correspondingly highest consumption of water while it was offered at a fixed price. However, these properties also reflected the largest price-induced changes. This is likely due to the fact that a significant portion of their consumption was for discretionary uses, which are not difficult to adjust. We must, however, bear in mind that this study was done in Florida –a rich American state in a rich country. It was also confined to single family houses, a distinction that further classifies the residents as belonging to an above average wealth bracket.

The study was carried out by four Florida water management districts. The decline in use shown with the increased price is general. The price-induced changes in water consumption vary according to the property value. Profile 1 represents the properties with the lowest assessed values, while profile 4 shows those with the highest. It is clear from the graph that the properties with the highest assessed values had the correspondingly highest consumption of water while it was offered at a fixed price. However, these properties also reflected the largest price-induced changes. This is likely due to the fact that a significant portion of their consumption was for discretionary uses, which are not difficult to adjust. We must, however, bear in mind that this study was done in Florida –a rich American state in a rich country. It was also confined to single family houses, a distinction that further classifies the residents as belonging to an above average wealth bracket.

The table below tries to account for the global picture. It shows the water tariffs in various cities in the world that represent most global income levels. The United Nation defined water scarcity as water availability below 1000m3 (35,300ft3) of fresh water per year. The table compares the price of this quantity of water to the country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per person. The water tariff data for the various cities is taken from The Pacific Institute and the GDP from the World Bank database.

|

Country |

City |

Water Tariff (in US$/m3) (2008) |

GDP/Person (in US$) (2008) |

Tariff Calculated for 1000m3(US$) of Water |

Percentage of the GDP/Person That Goes Toward the Water Tariff for 1000m3 |

|

Madagascar |

Antananarivo |

0.49 |

471 |

490 |

104 |

|

Kenya |

Nairobi |

0.34 |

786 |

340 |

43 |

|

India |

Kolkata |

0.15 |

1042 |

150 |

14 |

|

Egypt |

Cairo |

0.07 |

2157 |

70 |

3 |

|

China |

Beijing |

0.54 |

3414 |

540 |

16 |

|

Jordan |

Amman |

0.49 |

3797 |

490 |

13 |

|

Brazil |

Rio de Janeiro |

0.97 |

8623 |

970 |

11 |

|

Mexico |

Acapulco |

0.50 |

9508 |

500 |

5 |

|

Turkey |

Istanbul |

2.44 |

10379 |

2440 |

23 |

|

Venezuela |

Caracas |

0.21 |

11223 |

210 |

2 |

|

Russia |

Moscow |

0.82 |

11700 |

820 |

7 |

|

Japan |

Tokyo |

1.81 |

37972 |

1810 |

5 |

|

New York |

USA |

2.11 |

46760 |

2110 |

5 |

|

San Diego |

USA |

4.10 |

46760 |

4100 |

9 |

|

Copenhagen |

Denmark |

8.69 |

62596 |

8690 |

14 |

It is clear from the table that if an average resident of Madagascar (a lovely country that I visited for a few weeks) tries to pay his part of the tariff for this amount of water, he will end up paying more than his average share of the country’s GDP. He cannot do it. The same holds for much of Africa and even India. Meanwhile, an American that lives in New York ends up paying less than 5% of his share of the GDP, since New York doesn’t suffer from a shortage of fresh water, but an American in San Diego, which does suffer such a shortage, ends up paying about twice that. The water tariffs are not based merely on the costs of fresh water –instead, they usually include the costs of water treatments, water storage, transportation, collecting and treating waste water, billing, and in the case of privately run water companies, return on investment. In most cases the tariffs are regulated and should include recovery and maintenance of the water system and environmental criteria such as incentive to conserve. The large disparity between the tariffs is an indication that political considerations and ability to pay are important components of the mix. Since availability of water is essential for both the rich and poor, many of the basic requirements of sustainable systems of water supply and sanitation are either nonexistent or not being met.

A recent example from Venezuela illustrates some of these issues: Andre Soliani, a reporter from Bloomberg News wrote the following on September 4:

The carcass of a dead dog floats on the lake that supplies tap water to 750,000 Venezuelans. Witch doctor Francisco Sanchez has just dumped the previous night’s sacrifice from a cliff, contaminating the resource that has become more scarce than gasoline in Caracas.

The water from Lake Mariposa, polluted by sacrifices and garbage from a local cult,is pumped to a 60-year-old treatment plant that lacks the technology to make it safe for drinking, said Fernando Morales, an environmental chemistry professor at Simon Bolivar University in Caracas who has visited the site.

Eight kilometers (five miles) away from the lake, in Caracas, sales of bottled water are booming, with families paying the equivalent of $4.80 for a five-gallon jug, twice the price of gasoline.

“The treatment process has not adapted to the steady degradation of the water source,” Morales said in an interview at the university campus Aug. 22. “I wouldn’t use this water at home.”

Venezuela is an oil rich country that sits somewhere in the middle of the table in terms of GDP/person. Its water tariff is among the lowest in the table. Lower than Madagascar. Even so, 1000m3 of water amounts to approximately 50,000 five-gallon jugs that will cost $240,000 a year. This is way out of the average Venezuelan’s ability to pay – it is obvious that not every Venezuelan is taking part in the shift towards bottled water. Neglect has consequences.

Pingback: Virtual Water: With Concern About Future Availability of Fresh Water Worldwide, How Are We Using the Water We Have Now? | LCG Communications

Everybody has their own views on the topics of climate change. One of the most controversial topics would be Global warming. I feel that global warming is a result of the way of living we as humans have chosen, others feel that it is an inevitable part of nature. My brother is one of those people. According to him, humans have absolutely nothing to do with the subject and it’s just the way Earth functions. Climate and temperatures of different seasons cannot be effected the the gas and pollution emitted by us humans. He claims that many people are stating that the use of green house gasses is the cause of all the problems of global warming, but without green house gasses the earth would be unlivable to all living things currently on it.

I believe that in order to battle global warming and fossil fuel pollution, we must drastically reduce carbon emissions and increase the use of low-carbon energy sources that are now available resources to us. The U.S and the all other parts of the world should work together to further aim to reduce the emission levels of pollution we proclaim. Scientists can clearly state that warming temperatures, substantially of sea water, can help the formation of bigger more frequent and much more intense storms. The ominousness of climate change and the subject of global warming is gaining a greater momentum than once anticipated. Earlier studies once proclaimed that at the rate the global pollution is going the temperature will be greatly impacted, and will raise at a rate of 2 degrees Celsius by the end of this century. Although more recent studies done by scientists, are now stating that the once thought to be a 2 degree Celsius increase will reach about 4 or 6 degrees by the end of the century.

All and all, many people have their own opinion as to what is going on with the world. I believe that we should take advantage of the new hybrid and electric resources. Whats the worst that could happen if we utilize a different type of resource to save The Earth?