Walking outside in southern Arizona right now is akin to walking into a giant oven. Waves of heat waft toward you from all sides the moment you set foot out the door. We always joke, “but it’s a dry heat,” and it’s true: the humidity is so low that standing in the shade of a telephone pole feels several degrees cooler. The problem is, a few degrees doesn’t mean much once it’s over 105oF, much less over 110oF. Summer (June especially) is always ridiculously hot here—not for the faint of heart—but the last few years have gotten to absurd levels. This year is especially bad and last week, we suffered through a massive heat wave, part of the “heat dome” that has been affecting half of the country:

Tucson hit a high Tuesday of 115 degrees, shattering a record that stood for 125 years.

The mark was just two degrees below Tucson’s highest temperature ever recorded of 117 on June 26, 1990.

The National Weather Service said this was the fourth consecutive day in Tucson of record highs stretching from Saturday at 110, Sunday at 112, Monday at 112 to Tuesday’s 115.

Phoenix fared even worse:

The high temperature in Phoenix on Thursday hit 118, breaking previous records by 4 degrees, according to an update from the National Weather Service.

If you ask Arizonans what they do to beat the heat, their first answer will almost always be to stay inside an air-conditioned—or at least evaporative cooler-cooled—building (we call them “swamp” coolers here). Those I know who leave the house voluntarily usually choose to do so either in the very early morning or after the sun sets. As we have seen with the COVID-19 pandemic, however, that sort of answer implies a certain amount of privilege. Over the last year and a half, while much of the country switched to a remote work model, this was not an option for essential workers. There are just certain jobs you have to do in person.

The same is true for those who work outside in this heat and—though the risk is different—a lot of the same systems and structures that drove the socioeconomic and racial disparities in the COVID-19 crisis also apply here.

Social Factors

We know that a disproportionate number of black and brown people have been infected with and have died from COVID-19. There are several factors that have contributed to this. The CDC lists the following:

- Neighborhood and physical environment: There is evidence that people in racial and ethnic minority groups are more likely to live in areas with high rates of new COVID-19 infections (incidence).2,6

- Housing: Crowded living conditions and unstable housing contribute to transmission of infectious diseases and can hinder COVID-19 prevention strategies like hygiene measures, self-isolation, or self-quarantine. Increasingly disproportionate unemployment rates for some racial and ethnic minority groups during the COVID-19 pandemic8may lead to greater risk of eviction and homelessness or sharing housing. In some cultures, it is common for family members of many generations to live in one household.

- Occupation: Racial and ethnic minority groups are disproportionately represented in essential work settings such as healthcare facilities, farms, factories, warehouses, food processing, accommodation and food services, retail services, grocery stores, and public transportation.19,20,21,22 Some people who work in these settings have more chances to be exposed to COVID-19 because of several factors. These include close contact with the public or other workers, not being able to work from home, and needing to work when sick because they do not have paid sick days.23

- Education, income, and wealth gaps: Inequities in access to high-quality education can lead to lower high school completion rates and barriers to college entrance. This may limit future job options and lead to lower paying or less stable jobs. People with limited job options likely have less flexibility to leave jobs that may put them at higher risk of exposure to COVID-19.

Heat, like COVID, is most dangerous to those who are repeatedly exposed without protection—we saw what the lack of PPE did to so many of the front-line workers.

Over the past 30 years, heat waves have killed more people than all other weather-related natural disasters combined.

… Heat waves are most likely to affect people who work or live outdoors. The Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates that half of all U.S. workers have jobs that require them to be outdoors. Of those, 6.1 million are in construction, 4.6 million are in logistics, and 2.1 million are in agriculture.17 In July 2018, a United States Postal Service worker died on the job when the temperature hit 117 F.

OSHA also includes, “… baggage handlers, electrical power transmission and control workers, and landscaping and yard maintenance workers.” We can add miners, warehouse workers, and service/utility providers. These are all examples of manual labor—jobs that are traditionally done by people on the lower end of the socioeconomic scale, often including minorities and those with less education.

Legislation on Heat

As it stands, there is no federal standard in place to protect workers from dangerous heat conditions. I was pleasantly surprised to hear that there is a bill in the works to help rectify this problem and mitigate some of the danger. The Asunción Valdivia Heat Illness and Fatality Prevention Act was introduced in the Senate in October 2020 and in the House in March of this year. It is named after a farmworker who died after working for 10 hours straight (no water or breaks provided), picking grapes in 105oF heat.

Heat-related illnesses can cause heat cramps, organ damage, heat exhaustion, stroke, and even death. Between 1992 and 2017, heat stress injuries killed 815 U.S. workers and seriously injured more than 70,000. Climate change is making the problem worse. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the last seven years have been the hottest on record, with 2020 coming in only second to 2016. Farmworkers and construction workers suffer the highest incidence of heat illness. And no matter what the weather is outside, workers in factories, commercial kitchens, and other workplaces, including ones where workers must wear personal protective equipment (PPE), can face dangerously high heat conditions all year round.

The Asunción Valdivia Heat Illness and Fatality Prevention Act will protect workers against occupational exposure to excessive heat by:

-

Requiring the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) to establish an enforceable standard to protect workers in high-heat environments with measures like paid breaks in cool spaces, access to water, limitations on time exposed to heat, and emergency response for workers with heat-related illness; and

-

Directing employers to provide training for their employees on the risk factors that can lead to heat illness, and guidance on the proper procedures for responding to symptoms.

I like that it gives OSHA the power to enforce these safety measures but first, we’ll have to see if this bill makes any progress. According to an article in Civil Eats:

This is far from a new idea. In fact, it was first suggested in 1972 by the National Institute for Occupational Safety & Health, which was charged with recommending health and safety standards at the time. The recommendation was revised in 1986 and again in 2016, but has yet to be heeded.

Meanwhile, it’s not just those who are actively working in the heat that are suffering. Air conditioning is expensive but at temperatures like these, it’s dangerous to live somewhere without cooling amenities. For those without housing, it can be especially lethal:

Being homeless in an era of mega-heat waves is particularly deadly, as homeless people represented half of last year’s record 323 heat-related deaths across the Phoenix area. The homeless population has grown during the pandemic, and activists are now worried that an expiring eviction moratorium will mean others will lose their homes at the height of summer.

People who live in crowded or poorly insulated trailers or apartments or who cannot afford A/C are also at higher risk for serious heat exposure. This subset especially includes poor and elderly people, a disproportionate percentage of whom are people of color. Many of the same factors that the CDC credits with contributing to high COVID-19 mortality among minorities are equally relevant here, including housing, education, and education, income, and wealth gaps.

As in several other cities, there are a handful of “cooling centers” in Tucson and Phoenix, where people can go for “Indoor heat relief, water, snacks, and supplies during posted hours.” Again, this is a good start but seems like a small gesture given the vast number of people who are either homeless or whose homes are not sufficiently cooled (especially given that many of these people don’t know of these facilities).

Vaccines

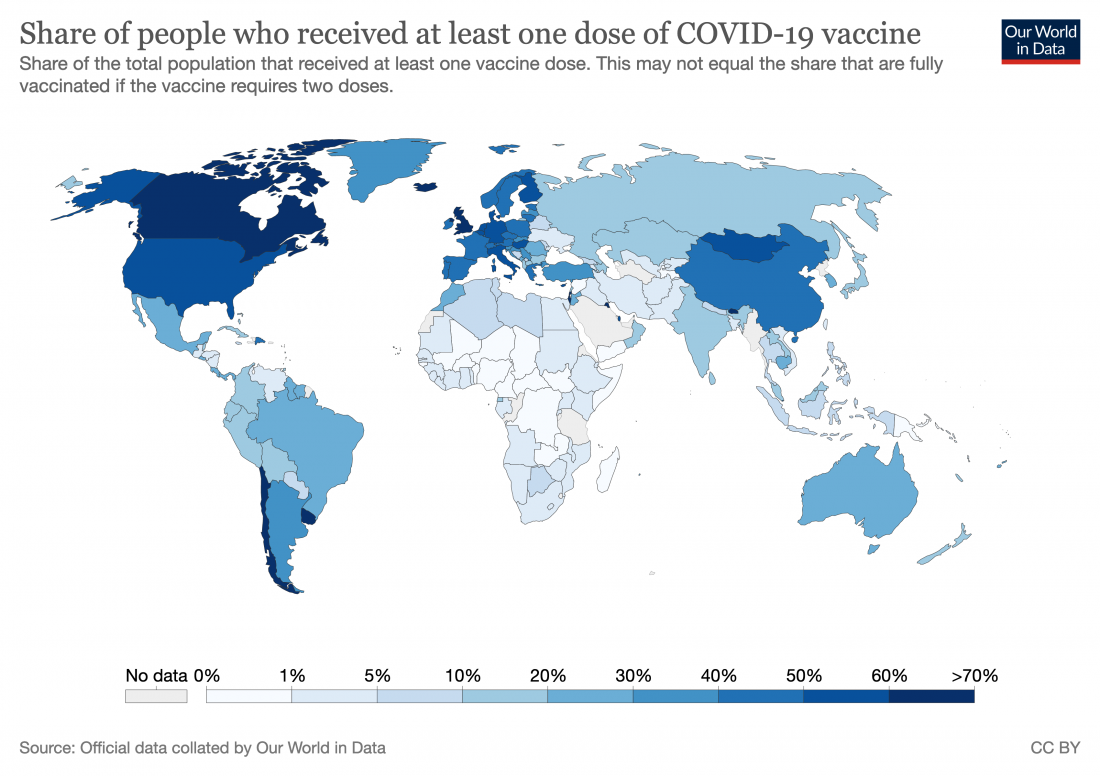

Looking again at the parallels with COVID-19, we can see the thoroughly asymmetrical way in which the vaccine has been rolled out: richer countries with access to and control over vaccine production have relatively high vaccination rates, while poorer countries have been left in the lurch:

Although more than 700 million vaccine doses have been administered globally, richer countries have received more than 87 per cent, and low-income countries just 0.2 per cent.

Here’s a visual representation:

In order to truly put the pandemic behind us, we need to ensure that the majority of the world gets vaccinated (sooner, rather than later) but that doesn’t quite seem to be happening. Even COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access (COVAX), an enterprise aimed at providing equitable access to COVID-19 vaccines, which has big goals, has so far been unable to realize them.

COVAX, managed by Gavi, along with the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations and WHO, was designed to stand on two legs: one for HICs [high-income countries], which would pay for their own vaccines, and the other for 92 lower-income countries, whose doses would be financed by donor aid.

… even with full financing, the COVAX roll-out has moved much more slowly than that in high-income countries (HICs). Speaker after speaker at the summit lamented the gross inequity in access to vaccines. “Today, ten countries have administered 75% of all COVID-19 vaccines, but, in poor countries, health workers and people with underlying conditions cannot access them. This is not only manifestly unjust, it is also self-defeating”, UN secretary general António Guterres told the gathering. “COVAX has delivered over 72 million doses to 125 countries. But that is far less than 172 million it should have delivered by now.” Of the 2.1 billion COVID-19 vaccine doses administered worldwide so far, COVAX has been responsible for less than 4%.

Next Steps

Both COVID and heat exposure reflect the far-reaching health effects of already existing economic (and socioeconomic and racial) disparities. These are all symptoms of systemic inequities—locally and globally; there is no easy, quick fix for things like poverty, homelessness, overcrowding, or a lack of medical infrastructure but we can make changes to more specific factors like work conditions, education, and access to healthcare.

The first step is always awareness: educating the world about these problems. From there, it takes a lot of teamwork and pressure to put any meaningful protections into place. The new legislation for heat safety standards gives me hope. But hope isn’t enough; thoughts and prayers don’t fix anything. We—especially those of us who benefit from existing racial and socioeconomic imbalances—need to take action, to keep advocating for more (enforceable) legislation and systemic changes.

I have been Micha’s editor and helped run this blog since the beginning. I’m excited to have the chance to contribute to Climate Change Fork again. My last blog was also about Tucson.

This article is so well written — summarizing the issues at hand, providing apt data and highlighting the many disparities that continue to keep the poor and working classes from accessing basic necessities for life, especially applicable to health coverage and public health amenities. You have encouraged me to check where the cooling centers are in this area.

i like this article about Heat and COVID Disparities, For more than a year, the whole planet is suffering from the corona pandemic. It caused a lot of panic, fear, and anxiety.

People started to worry more about themselves, their families, and their beloved ones, which led them to take some more protective actions.

A lot of our daily routine has changed; staying home is all we can do now. And if we have to go out a lot of precautions must be taken.

We had really missed being in contact, hugging each other, shaking hands, and live freely, thanks for sharing this info and explanation

Excellent work Sonya! Your writing is clear and a wonderful educational tool. So proud of you.

Very interesting comparisons. Thanks for this well written article.

Of course!

Excellent Sonia! When you learn about publishing, is here any chance we can post on our National PSR – AZ chapter page?

Thank you Sonya for this great blog. I would like to use your blog as an opportunity to invite anybody that suffers from heat stress to share his/her experiences with all of us.

The “Heat Dome” that you mentioned brings to mind Dubai in the UAE (see the September 10, 2019 blog) with the opening picture of the proposed “Mall of the World” over the city as a solution to similar heat impact to that you are describing. The dome here should extend over Arizona with open “invitations” to California, Nevada, and New Mexico with good expansion capabilities. If my memory serves me right, discussions on this have already started. In coming blogs, I will try to estimate the timeline that will be needed to extend the concept globally.