Back in April, I outlined President Biden’s new American Job Plan. Granted, the $2.3 trillion plan was more of a wish list than a proposal; given the 50-50 split in the Senate and the narrow majority in the House, it has no chance of being approved. However, the proposal was important in how it outlined the priorities of the new administration. In that blog, I photo-coded the sections that I consider to be climate change-related, whose budget totaled $1.35 trillion. Below are the two key paragraphs from that blog:

In Tables 1-3, I have highlighted the entries that can be associated with climate change, and which I will speak to specifically in future blogs. Of course, the whole effort addresses a multitude of overlapping issues; none of the items can be exclusively associated with one of the entries of my earlier Venn diagram. Rounding up from the sum of the estimated costs for all of the entries, we come to $1.9 trillion. With the addition of the $400 billion for in-home care, we reach the plan’s quoted $2.3 trillion. The sum of the highlighted, climate-related items comes to $1.35 trillion, 70% of the total cost.

At this stage, the plan is a proposal, not a legislative commitment. In this sense, it is similar to the Paris Agreement (great intentions but little enforcement/implementation power). Right now, the size and the scope of the plan make it vulnerable to cherry-picking by both supporters and opponents. Serious questions remain in terms of timing (the plan is supposed to take the rest of the decade) and payment (suggested distribution over the next 15 years). The soonest, most important commitment in terms of timing is the promise of carbon-free electric power delivery by 2035.

The next logical step was to wait for this wish list to be parceled into smaller, more manageable sections—a strategy that would give each piece a much better chance of passing through into law. About a week ago, we saw the first significant progress in this process with the United States Innovation and Competition Act of 2021:

Senate Overwhelmingly Passes Bill to Bolster Competitiveness With China

The wide margin of support reflected a sense of urgency among lawmakers in both parties about shoring up the technological and industrial capacity of the United States to counter Beijing.WASHINGTON — The Senate overwhelmingly passed legislation on Tuesday that would pour nearly a quarter-trillion dollars over the next five years into scientific research and development to bolster competitiveness against China.

The measure, the core of which was a collaboration between Mr. Schumer and Senator Todd Young, Republican of Indiana, would prop up semiconductor makers by providing $52 billion in emergency subsidies with few restrictions. That subsidy program will send a lifeline to the industry during a global chip shortage that shut auto plants and rippled through the global supply chain.

The bill would sink hundreds of billions more into scientific research and development pipelines in the United States, create grants and foster agreements between private companies and research universities to encourage breakthroughs in new technology.

This has not passed into law yet. The proposed law still has to be approved by the House with a simple majority. I sincerely hope that the House does not erect obstacles to this happening and that the president signs it.

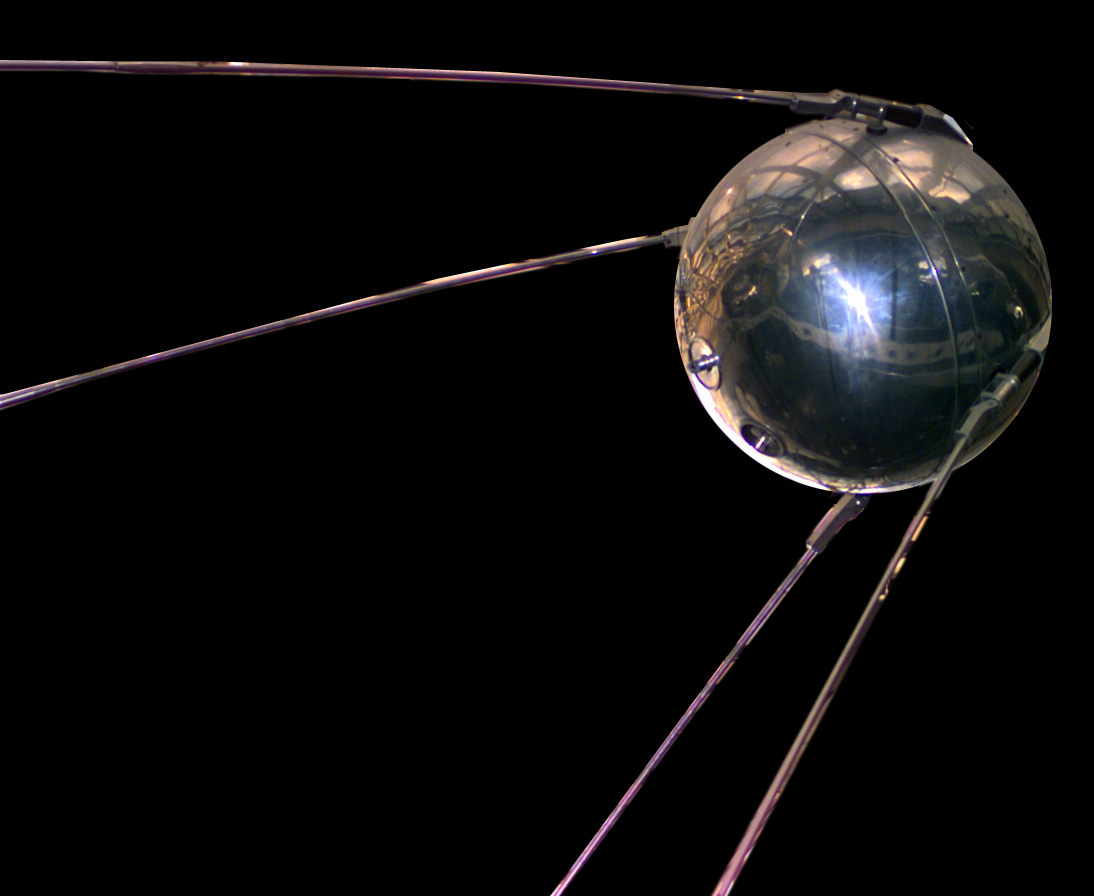

As we see in the NYT piece above, the legislation’s success in the Senate was largely a result of its being framed as a measure to protect the country’s security and industry from China’s success. I thought back to 1957. The Soviet Union managed to launch Sputnik, the first satellite, into space as I was finishing high school in Israel. The US Senate reacted with new legislation, which was presented similarly:

On October 4, 1957, the Soviet Union shocked the people of the United States by successfully launching the first earth-orbiting satellite, Sputnik. During the Cold War, Americans until that moment had felt protected by their technological superiority. Suddenly the nation found itself lagging behind the Russians in the Space Race, and Americans worried that their educational system was not producing enough scientists and engineers. Sometimes, however, a shock to the system can open political opportunities.

On the day Sputnik first orbited the earth, the chief clerk of the Senate’s Education and Labor Committee, Stewart McClure, sent a memo to his chairman, Alabama Democrat Lister Hill, reminding him that during the last three Congresses the Senate had passed legislation for federal funding of education, but that all of those bills had died in the House. Perhaps if they called the education bill a defense bill they might get it enacted. Senator Hill—a former Democratic whip and a savvy legislative tactician—seized upon on the idea, which led to the National Defense Education Act.

There had been strong resistance to federal aid to education, but as public opinion demanded government action in the wake of Sputnik, the Senate once again moved ahead with its education bill. Knowing that opponents in the House remained resistant, Senator Hill conferred with another Alabama Democrat, Representative Carl Elliott, who chaired the House subcommittee on education. Meeting in Montgomery, they devised a strategy for getting the NDEA enacted. They framed the debate around the question of whether federal funds should go to students as grants, as the Senate preferred, or as loans. Opponents in the House denounced the notion of grants as “socialist.” When the House prevailed on loans, the rest of the Senate’s version of the bill swooped through to passage. In fact, the grants versus loans debate had been a ploy. Senator Hill and Representative Elliott realized that having voted the same bill down repeatedly in the past, the House had to have something on which it could win.

The National Defense Education Act of 1958 became one of the most successful legislative initiatives in higher education. It established the legitimacy of federal funding of higher education and made substantial funds available for low-cost student loans, boosting public and private colleges and universities. Although aimed primarily at education in science, mathematics, and foreign languages, the act also helped expand college libraries and other services for all students. The funding began in 1958 and was increased over the next several years. The results were conspicuous: in 1960 there were 3.6 million students in college, and by 1970 there were 7.5 million. Many of them got their college education only because of the availability of NDEA loans, thanks to Sputnik and to Senator Hill’s readiness to seize the moment.

The 2021 Innovation and Competition Act has the potential to have a similarly strong impact on both education and research and development (R&D), globallye. Once the bill passes into law, I will elaborate on these possibilities, including how they may benefit research aimed at facilitating climate change mitigation and adaptation.

One of the main factors that facilitated such rare bipartisan support for this legislation is the feeling (and the fear) that allowing the Chinese to increase its R&D efforts while we decrease our own, constitutes a real danger to our national security.

Tables 1 and 2 below use data from recent OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development) compilations to explore this issue (I am using the Wikipedia source for Table 1 because it also includes data for countries that are not members of OECD). Table 1 shows the 10 largest spenders on this issue and the percentage they spent on R&D.

Table 1 – R&D as % of GDP and per capita of the 10 largest spenders in 2019

| Country | Expenditures on R&D

(Billions of US$, PPP) |

% of GDP (PPP) | Expenditure on R&D per capita (US$ PPP) |

| US | 613 | 3.1 | 1,866 |

| China | 515 | 2.2 | 368 |

| Japan | 173 | 3.2 | 1,375 |

| Germany | 132 | 3.2 | 1,586 |

| South Korea | 100 | 4.6 | 1,935 |

| France | 64 | 2.2 | 944 |

| India | 59 | 0.65 | 43.4 |

| UK | 52 | 1.8 | 762 |

| Taiwan | 43 | 3.5 | 1,822 |

| Russia | 39 | 1.0 | 263 |

Table 1 shows the expenditure in terms of PPP (Purchasing Price Parity). For comparison, the 2019 GDP of China, measured in nominal US$, was $14.3 trillion; in PPP adjusted currency, that amounts to $23.5 trillion—larger than that of the US for the same year (per definition, the US nominal and PPP exchange rates are the same). In other words, in relative terms, China is spending significantly more on R&D than the US does.

Table 2 steps back to look at the US and China’s changes in expenditures over the last 10 years.

Table 2 – R&D of US and China as a percentage of GDP

| Year | China | US |

| 2009 | 1.665 | 2.813 |

| 2010 | 1.714 | 2.735 |

| 2011 | 1.780 | 2.765 |

| 2012 | 1.912 | 2.682 |

| 2013 | 1.998 | 2.712 |

| 2014 | 2.022 | 2.721 |

| 2015 | 2.057 | 2.719 |

| 2016 | 2.100 | 2.788 |

| 2017 | 2.116 | 2.847 |

| 2018 | 2.141 | 2.947 |

| 2019 | 2.235 | 3.07 |

Looking at both tables, one might be tempted to question the assertion that China is so far ahead of the US in dedicating resources to R&D. However, the data are all given as percentages of the countries’ GDP. In nominal US$, the GDP of China for the period 2009 – 2019 increased from $5.1 to $14.3 trillion, a growth of 180%. The US GDP over the same period went from $14.4 to $21.4 trillion, an increase of 49%. That means even though China’s percent of expenditures on R&D looks approximately constant in Table 2, its GDP over this period grew more than three times faster than that of the US, while its share of expenditure on R&D grew at roughly the same ratio.

Interestingly, we can also see from Table 2 that the US R&D expenditures were slowing down from 2009 – 2016 but they experienced a significant increase from 2016 – 2019, under the Trump administration. That said, we’d need to do some additional research to find out whether this increase was comprehensive or went almost entirely toward military research.

Once the new legislature is approved by the House and signed by the president, I’ll delve more into its possible impact on expenditures for climate change mitigation and adaptation.