I started to write this blog a day after President Biden presented his infrastructure plan in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The location’s symbolism was obvious; this was the same city where President Trump announced his withdrawal from the Paris Agreement:

I was elected to represent the citizens of Pittsburgh, not Paris. (Applause) I promised I would exit or renegotiate any deal which fails to serve America’s interests. Many trade deals will soon be under renegotiation. Very rarely do we have a deal that works for this country, but they’ll soon be under renegotiation. The process has begun from day one. But now we’re down to business.

President Biden announced the US return to the Paris Agreement via executive order on the day of his inauguration. His real assurances, however, came during his April 1st speech, when he proclaimed his intention to codify his administration’s commitment to climate change mitigation via an innovative new piece of legislation. The plan is big on almost every level. Not only does he address the return to the Paris Agreement but he also details his approach to the overlapping issues of COVID-19, climate change, jobs, equity, and population rise (see my Venn diagram in my August 4, 2020 blog).

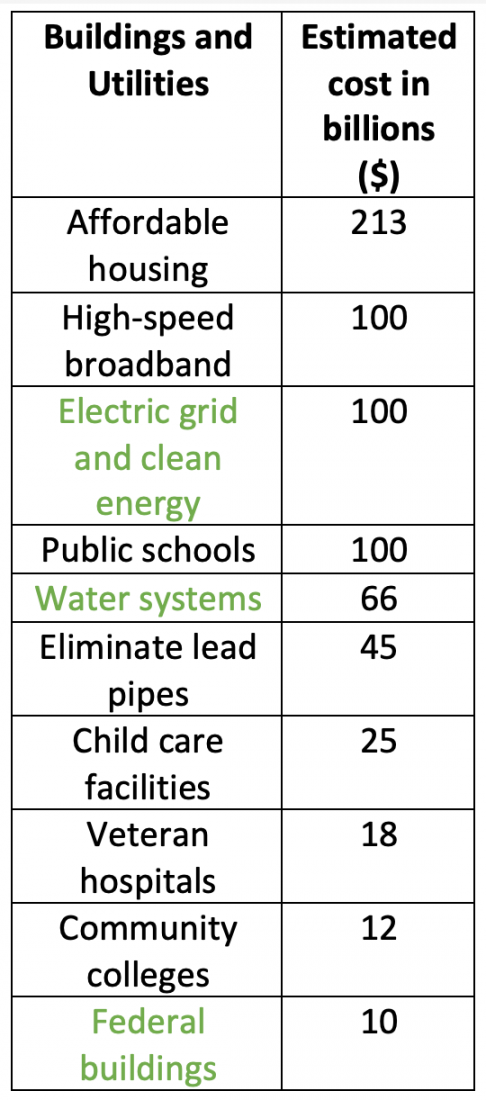

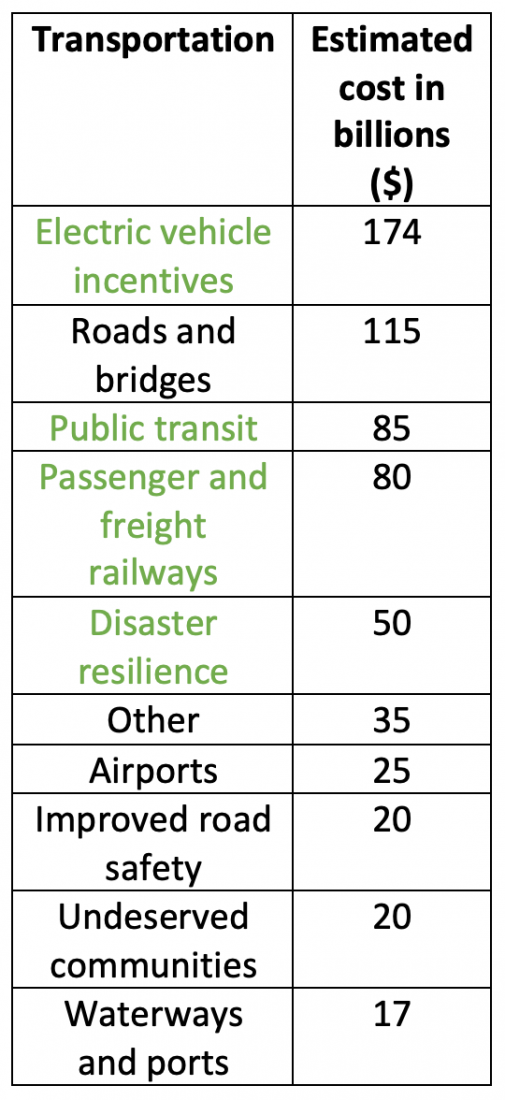

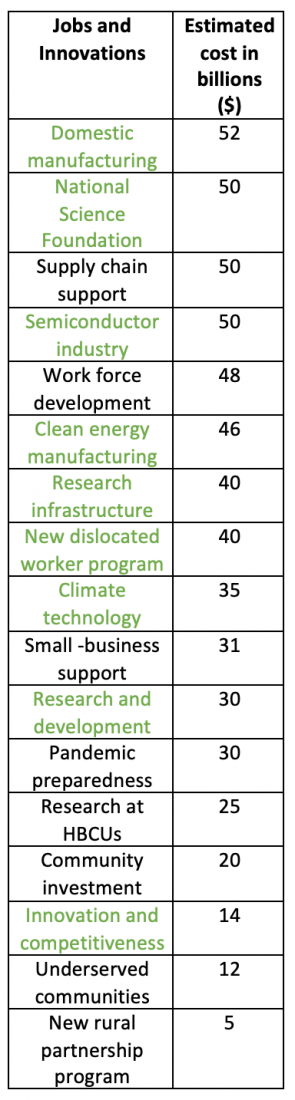

Tables 1-3 show the details of this new “American Jobs Plan.” I will try to address them in the next few blogs. This week I want to highlight the magnitude of the proposed budget and its distribution, specifically in the context of the global post-Paris-Agreement situation.

Tables 1, 2 & 3 – Details of President Biden’s “American Jobs Plan”

|

|

In addition to the three sections shown above, $400 billion are proposed for “in-home care.” This money is targeted to: “Expand access to caregiving for those who are older and those with disabilities, and to improve pay and benefits for care givers.”

These are the main goals of the plan’s three sections:

Transportation: To revitalize the aging or crumbling corridors that get American people and products from place to place, while reducing the sector’s reliance on fossil fuels that drive climate change.

Buildings and Utilities: To make homes and commercial buildings more energy efficient; reduce the lead hazards of old water pipes; bridge the urban-rural digital divide; and modernize the electrical grid for greater reliability and wider deployment of low-carbon electricity.

Jobs and Innovations: The president has said that he wants to position America to compete against China and other rivals in the race to build and dominate industries of the future, like semiconductors and advanced batteries.

In Tables 1-3, I have highlighted the entries that can be associated with climate change, and which I will speak to specifically in future blogs. Of course, the whole effort addresses a multitude of overlapping issues; none of the items can be exclusively associated with one of the entries of my earlier Venn diagram. Rounding up from the sum of the estimated costs for all of the entries, we come to $1.9 trillion. With the addition of the $400 billion for in-home care, we reach the plan’s quoted $2.3 trillion. The sum of the highlighted, climate-related items comes to $1.35 trillion, 70% of the total cost.

At this stage, the plan is a proposal, not a legislative commitment. In this sense, it is similar to the Paris Agreement (great intentions but little enforcement/implementation power). Right now, the size and the scope of the plan make it vulnerable to cherry-picking by both supporters and opponents. Serious questions remain in terms of timing (the plan is supposed to take the rest of the decade) and payment (suggested distribution over the next 15 years). The soonest, most important commitment in terms of timing is the promise of carbon-free electric power delivery by 2035.

Meanwhile, with regards to the rest of the world, a blog from Columbia University’s Earth Institute summarized the global climate change mitigation efforts since the Paris Agreement:

The Paris Agreement calls for countries to make their pledges to reduce emissions — called nationally determined contributions (NDCs) — more ambitious every five years; the first step-up was to occur at the end of 2020. According to the Climate Vulnerable Forum, only 73 countries proposed revised goals, with 69 countries including the E.U., U.K., Argentina, and Ethiopia submitting more ambitious emissions reduction targets.

The E.U. pledged to cut emissions 55 percent from 1990 levels by 2030, and the U.K. promised to cut emissions 68 percent from 1990 levels by 2030. While China has not formally submitted an updated pledge, at the summit it declared that it would aim for carbon neutrality by 2060 and submit an enhanced NDC for 2030 in line with this goal; China also aims to peak its emissions by 2030.

Several other countries, including Russia, have kept the status quo. Brazil’s new pledge has effectively backtracked, and while Brazil did propose a 2060 net-zero goal, this would be contingent on receiving $10 billion a year in climate finance from other countries. Later this year, at COP 26, all other parties will have to submit updated NDCs.

The critical question, however, is whether or not countries can translate their long-term net-zero goals into the short-term policies that are necessary to realize them.

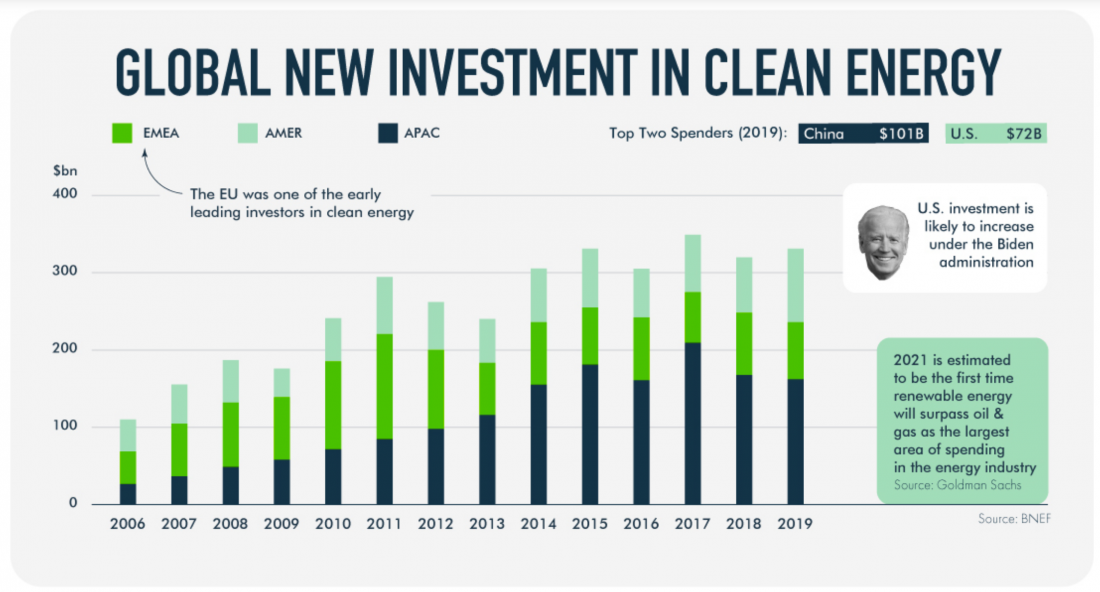

Figure 1 presents a comparison between the three largest economies’ major investments in sustainable energy resources.

Figure 1 – Global clean energy investments: Europe, Middle East, and Africa (EMEA) vs. the Americas vs. the Asia Pacific region (APAC)

I will continue to follow both domestic and foreign implementation/follow-up of these plans and commitments over the next few months.

I did not realize the Paris agreement calls for an updated ambition every 5 years. It is a shame how few countries (relatively) updated with more ambitious goals. One of the struggles of deals like this are the changes in governments and world leaders over time. We have seen a wild shift in America’s climate change priorities since 2015. While other countries may be more stable with opposing parties still believing in climate change, there is still a danger of an administration that doesn’t see it as a huge priority. I think that is partly reflected in the amount of countries who failed to update their goals for 2020. President Biden is promising big goals, but his administration’s priorities are currently more focused on ending the pandemic and establishing an economic recovery.