When I started writing this blog on Wednesday morning, we were just beginning to see Hurricane Ida’s effects as it climbed through the Northeast, scheduled to pass through my home city, NYC. Two seemingly unrelated pieces in that day’s NYT caught my attention: one was about the aftermath of Ida in New Orleans and the other was an opinion piece related to climate change. Both pieces spoke about environmental migrations and the US’s (in)ability to handle extreme weather events.

We can see climate change’s mark on Hurricane Ida by way of the “rapid intensification” process, where a low-rank storm passes through hot water, which rapidly accelerates it into a much more intense storm. The warming of the sea and the lower atmosphere (the troposphere) also results in a major increase in atmospheric water vapor, which leads to extreme rainfall and floods. Energized by the Gulf of Mexico’s very warm water, on Sunday, in just a few hours, Ida went from a category 1 hurricane off the coast to a category 4 major storm as it touched land in southern Louisiana. New Orleans, and other southern Louisiana residents, were strongly advised to leave town and head north. A mandatory evacuation was not issued in most places for the simple reason that there was no time to enforce one.

Understandably, the storm drew many comparisons with 2005’s Hurricane Katrina, which hit New Orleans and killed 1,800 people, as well as causing an estimated $125 billion in damages. Following Katrina, the Army Corps of Engineers spent around $15 billion to upgrade New Orleans’ levee system, with the hope of preventing repeat vulnerability. Hurricane Ida was the first real test of this upgraded system. By Wednesday, it was clear that the upgraded system had successfully withstood the challenge and prevented Katrina-scale flooding in the area. However, major flooding is not the only infrastructural damage that a category 4 hurricane can inflict; the electric grid system in the area became a total wreck and more than a million people were cut off from power. Meanwhile, water treatment facilities also took heavy damage, leading to a serious shortage of safe drinking and washing water. Furthermore, state-wide and New Orleans-based officials strongly advised Louisianans who had evacuated before the storm not to return to their homes until further notice—creating, in an instant, thousands of temporary environmental refugees.

The NYT opinion piece from the same day, “When Climate Change Comes to Your Doorstep,” gives a sense of the national climate crisis:

We are now at the dawn of America’s Great Climate Migration Era. For now, it is piecemeal, and moves are often temporary. Brutalized by hurricanes, flooding and a winter storm, Lake Charles, La., residents have been living with relatives for months. In early August, the Dixie fire — the largest single fire in recorded California history — claimed at least one entire town, and locals took to living in tents. Apartment dwellers in Lynn Haven, Fla., were forced from their homes to slosh through streets flooded by Tropical Storm Fred. The evacuee tally has continued to rise, from New Englanders in the path of Hurricane Henri to flood survivors in North Carolina and Tennessee to people escaping fire in Montana and Minnesota.

But permanent relocations, by individuals and eventually whole communities, are increasingly becoming unavoidable.

The op-ed also describes real estate company’s efforts to estimate climate change vulnerability by zip code. It quotes statistics that 1.7 million disaster-related displacements were recorded in 2020.

On Wednesday evening, Ida hit NYC in full. By Thursday morning, it became obvious that NYC and the rest of the Northeast were totally unprepared. Although the storm as a whole was considerably downgraded by the time it reached us, we still faced intense flooding. In fact, the number of fatalities here exceeded those from the Gulf of Mexico. Many of these victims in NYC drowned in small, windowless basement apartments as flooding reached the ceiling.

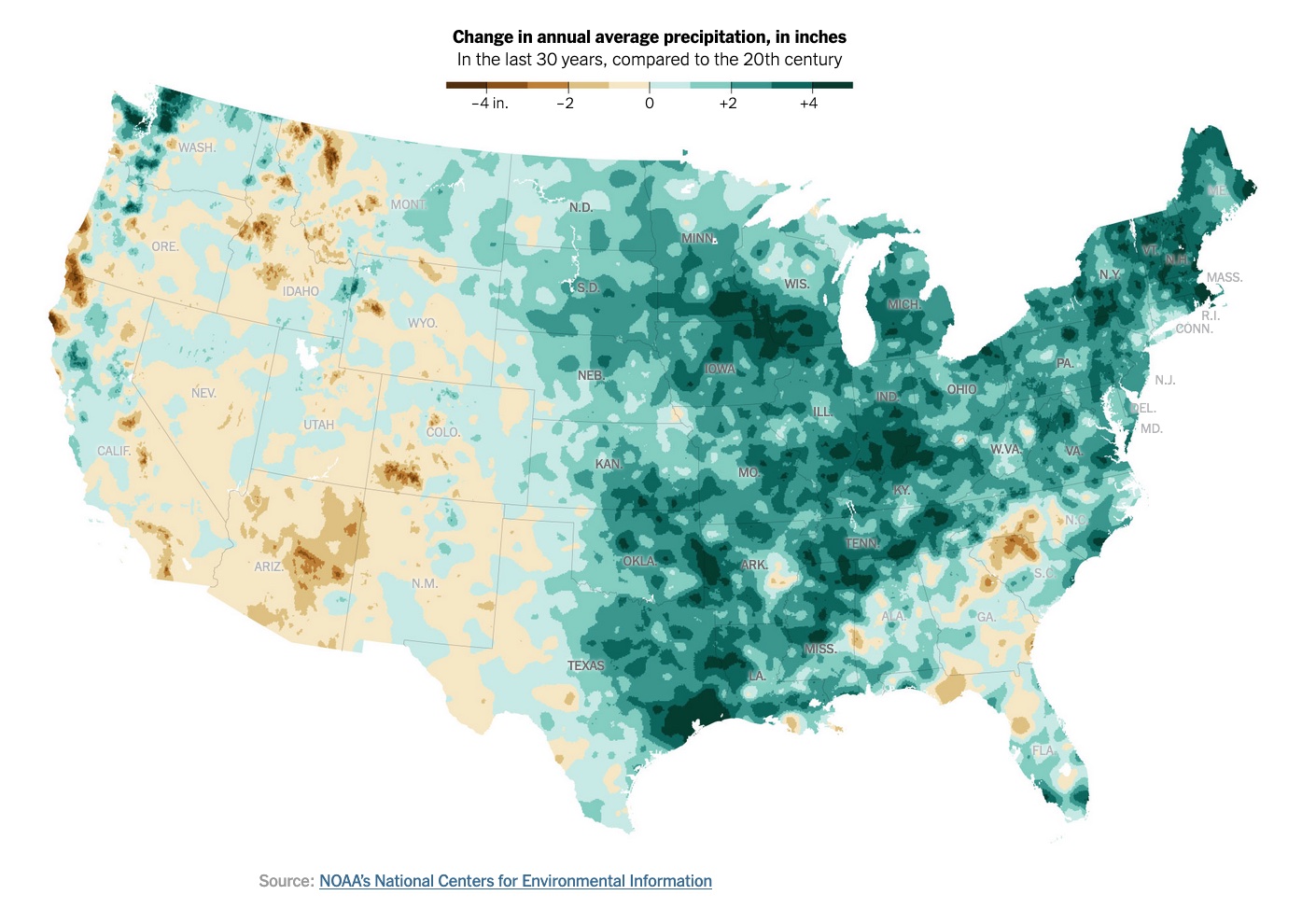

An article in the NYT from two weeks ago featured the map below of two Americas: one dry and the other wet. Climate change triggers and amplifies both of these extremes. Both uproot thousands of people, creating scores of environmental refugees.

Figure 1 – Map of two Americas: the dry (brown) and the wet (green)

This blog focused on the wet part of the country. However, I ended last week’s blog citing an article about the unsustainable situations in Phoenix, Arizona, and Las Vegas, Nevada. These cities are located squarely in the dry part of the country, with summer temperatures this year setting three-digit records. Yet, the last census indicates that people are flocking there. In fact, Phoenix has become the fifth most populated city in the US.

This phenomenon of climate change-driven extreme weather—both wet and dry—has dire consequences. Nor is it confined to the US. Next week I will try to cover the issue abroad.

It is for sure that we are not well prepared for natural disasters. With extreme weathers, people are forced to evacuate, but the real concern is “Where?”. Where can these helpless people go after leaving their hometown? What should they do to obtain food and resources? When will they ever return home? By the time these questions are answered, it is already too late. Many people have already been injured, killed, and their homes are damaged. This article reminds me of Hurricane Ian that is currently occurring in Florida. I’m pretty sure that constant raining days in New York has something to do with this hurricane going on. This article also reminds me of the flood that happened one year ago. I remember there was these posts on Instagram where the flood reaches an average woman’s waist in the train station. It was crazy!

I definitely agree about the lack of preparation against extreme weather conditions. Recent extreme weather conditions have felt constant and unstoppable. Extreme weather conditions have proved that they do not discriminate as places that are cool, hot, wet, and dry have felt its effects and have been facing extreme weather events more and more frequently. I think one very common factor of this lack of preparation is the mediocrity of infrastructure. For instance, when the snowstorm in Texas happened, the state was completely incompetent at handling it. Many of the buildings there didn’t have the capacity for heating, just like buildings in colder places such as Portland didn’t have mechanisms for cooling during the heat waves over the summer, as there was never any need. While lackluster infrastructure is to blame, I also think that so many people didn’t expect the climate to change so quickly and for weather conditions to become so bad. Maybe if there was more time, there could be efforts at fixing infrastructure but it seems like time isn’t a luxury people can afford anymore.