The theme of the blog may look familiar to longtime readers of this blog, even if the exact title is new. If you put the title in the search box without quotation marks, you will get many related entries. The term “power and politics in academia” (again, without quotation marks) yields one entry: a blog from July 18, 2017, that discusses the driving forces of the Anthropocene. I also discussed the role of internal politics in academic institutions recently (December 28, 2021):

This observation is routinely attributed to Henry Kissinger who in a 1997 speech at the Ashbrook Center for Public Affairs at Ashland University, said: “I formulated the rule that the intensity of academic politics and the bitterness of it is in inverse proportion to the importance of the subject they’re discussing. And I promise you at Harvard, they are passionately intense and the subjects are extremely unimportant.”

My focus today is on the role that politics play in teaching and learning, as it directly impacts students. As I have mentioned in earlier blogs (see January 19, 2022, where I discuss cherry-picking and bias), there is a large power differential between teachers and students; bias on the part of teachers has a strong impact on student learning and needs to be discussed.

This issue of bias in student-teacher interaction has been covered extensively but mostly in terms of preferential treatment or neglect of certain students over others, based on characteristics such as gender, race, voluntary class participation, past performance, etc. Here, I want to cover biases that can be associated with an outlook on reality, including political biases.

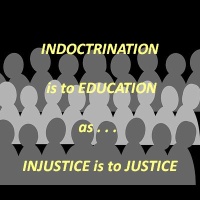

This image is from https://whatiseducationhq.com which has some really interesting things to say on this same topic.

The first driving force that made me return to this issue is the mix of sex and power—something we hear about almost daily. The issue is institutional but not confined to academic institutions. However, when we speak of it in terms of academic institutions, we usually limit it to higher education because students in high schools and elementary schools are generally too young for consent, and our laws governing such behavior are anchored on the student’s age. In colleges and universities, most students are old enough for consent, so the laws and rules of behavior anchor instead on power differentials. Presently, every institution has its own set of regulations about the sexual behavior of its employees. My own institution (City University of New York) has a 23-page document. Here’s a key paragraph:

Amorous, dating or sexual activity or relationships (“intimate relationships”), even when apparently consensual, are inappropriate when they occur between a faculty member or employee and any student for whom he or she has a professional responsibility. Those relationships are inappropriate because of the unequal power dynamic between students and faculty members and between students and employees who advise or evaluate them, such as athletic coaches or workplace supervisors. Such relationships necessarily involve issues of student vulnerability and have the potential for coercion. In addition, conflicts of interest or perceived conflicts of interest may arise when a faculty member or employee is required to evaluate the work or make personnel or academic decisions with respect to a student with whom he or she is having an intimate relationship. Finally, if the relationship ends in a way that is not amicable, the relationship may lead to charges of and possible liability for sexual harassment.

As I said, the restrictions are strictly based on power differentials rather than age.

Since I mostly teach courses that focus on environmental issues, my thinking is as follows: Society puts so much attention on the role of power in personal relationships but gives relatively less attention to the role of power in teaching. At least in the US, however, the latter role has become highly politicized, especially recently. Here are a few examples:

When it came out, The New York Times’ “1619 Project” became quite controversial, and remains so:

long-form journalism endeavor developed by Nikole Hannah-Jones, writers from The New York Times, and The New York Times Magazine which “aims to reframe the country’s history by placing the consequences of slavery and the contributions of Black Americans at the very center of the United States’ national narrative.”

Additionally, some states have made a popular activity of banning certain books in schools. This includes Maus, the graphic novel about the Holocaust.

Many of us learned, with some horror—whether through the “Inherit the Wind” movie or otherwise—about the Scopes Monkey Trial of 1935, in which segments of society tried to censor teachers from teaching about evolution.

We are now moving through three major global transitions that impact us all: COVID-19, climate change, and the massive reduction in population growth that in many countries is manifesting as population decline (February 1, 2022). The adaptive steps that society is taking to live with these changes are a precious learning opportunity. They can be a laboratory for our students, where they can learn how to use their knowledge in practical settings that will benefit them long after they finish school. Two out of the three transitions will affect my students for much longer than they will me (just in terms of age). However, all three have become highly political.

My climate change classes best demonstrate the related societal impacts and responsibilities of various scenarios. When I ask students about the possible personal impact, I get the response (almost always from female students) that they have decided not to bring kids into this kind of world. These are big decisions, which are politically loaded. We often describe the opinions of climate deniers, but since these are science courses, the arguments must be data-based. Aside from uncertainties in predictions of the future, there is not much science to support climate deniers (according to my data-based bias).

Talks with my colleagues in different departments expose a variety of attitudes regarding how to address similar problems. A Jewish friend was teaching a course on the recent history of the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, with a number of Muslim students taking the course. Both of us (the teacher and I) know that the version of this conflict many Muslim students know often differs from the version known to their Jewish peers. I asked him how he handles the bias disparity. His answer was that he bases his teaching on original documents. I kept quiet. We both know that he is the one who selects which original documents his class discusses. His cherry-picking of documents might not be such a big issue because his class is an advanced elective, and it is easy for the students to research his background.

When I discussed these issues with another colleague who teaches political science and told him that I am trying to leave my politics out of the classroom, he responded that, in his opinion, everything is driven by politics.

In all these cases, none of us addressed the inherent power asymmetry between teachers and students.

Often, we are not fully aware of our biases. Even if our biases are pointed out to us, if we try to correct for them, we may end up with biases in the opposite direction. In my opinion, we cannot eliminate biases, but we can make them more transparent, such that students can normalize their analysis as part of their learning experience. One good way to accomplish this is by basing more of the course material on class conversation and group teaching: Team-Based Learning (TBL).

Occasionally, students complain about biased teachers. These complaints can go through various routes, including family, press, courts, etc. but most complaints end up with the administration of the institution. Some faculty (in the US now about 20%) has tenure for life—a measure designed to protect their academic freedom but which is conditional on following certain codes of conduct (see for various aspects of these issues:

https://www.aaup.org/article/academic-freedom-online-education

Lifetime job tenure is not restricted to academia but without its protection, bias complaints can result in job termination.

The COVID-19 pandemic that triggered such advancement in remote learning offers one way to address these issues. Like many others, during the last two years, I have been teaching online. In one of the climate change courses that I taught, I used the TBL system. I divided the class into groups, which, during class time, I put into separate “rooms” where they could discuss the issues. Outside of class, I opened a Discussion Board on BlackBoard (A commonly used application) where they could communicate, letting them know I would visit periodically to monitor their discussions and add comments or answer questions as needed. A few students commented that opening a separate WhatsApp group might help. I agreed but I told them that group would be totally their own. The results were interesting.