During the active academic year, my main focus for this blog is to provide help to my students in their research assignments. I try to address the blog’s main focus—global transitions (with an emphasis on climate change)—while also staying relevant to the different courses and and being helpful to the general public. Over the previous few weeks, I’ve focused on students who research “Campus as a Lab” as a learning tool. Today, I am starting to address the needs of more advanced students—specifically, trying to quantify attributions of global transitions to local events with a focus on climate change.

Catastrophic floods are now hitting all over the world (for a comprehensive list from recent months, see Al Jazeera.). The devastating flooding in Pakistan probably attracted the most global attention, but by their nature, floods are local events that attract the most attention from the citizens of the affected country. In the US, most Americans are focusing on hurricane Ian’s impact and the devastating floods it wreaked in Florida. However, given that the US has less than a month before important elections, it’s no surprise that some of the responses to extreme weather are being politicized (“Florida’s GOP Leaders Opposed Climate Aid. Now They’re Depending on It.“)

For over a generation, climate change, with all its aspects, has been a politically divisive issue in the US. I have covered the topic extensively throughout this blog’s more than 10-year run. Democrats have argued that most of the global warming, as measured following the start of the Industrial Revolution, originates from human activities—primarily, the shift to fossil fuels as our main source of energy. Meanwhile, Republicans have largely admitted that the warming is taking place but claimed that there is considerable uncertainty about its causes, concluding that we should not take major steps to change our energy sources until we are more certain of the causation. A significant fraction of people who hold this opinion attribute the warming to “natural” causes and ascribe extreme consequences (e.g. extreme weather) to “biblical” causes. In other words, the phenomena are perpetrated independently of humans and we should just learn to live with them.

Figure 1 – Noah’s Ark (Source: Library of Congress via Rawpixel)

Figure 1 shows the most famous biblical flood and Noah’s individual attempt to adapt by building an ark and inviting pairs of animals to share with him its safety (I mentioned Noah’s Ark before, in a different context– February 4, 2020). The attribution, in this case, is clear: God made the flood as punishment for bad human behavior. The proposed mitigation for human sin is also clear: wipe out all badly-behaving humans but save one well-behaved family with the hope that they will multiply and create an improved human population. What’s less clear is how the animals that were fated to survive were chosen.

Wikipedia provides a short summary of Noah’s ark.

Noah’s Ark (Hebrew: תיבת נח; Biblical Hebrew: Tevat Noaḥ)[Notes 1] is the vessel in the Genesis flood narrative (Genesis chapters 6–9) through which God spares Noah, his family, and examples of all the world’s animals from a world-engulfing flood.[1] The story in Genesis is repeated, with variations, in the Quran, where the Ark appears as Safinat Nūḥ (Arabic: سفينة نوح “Noah’s ship”) and al-fulk (Arabic: الفُلْك).

Searches for Noah’s Ark have been made from at least the time of Eusebius (c. 275–339 CE), and believers in the Ark continue to search for it in modern times, but no confirmable physical proof of the Ark has ever been found.[2] No scientific evidence has been found that Noah’s Ark existed as it is described in the Bible.[3] More significantly, there is also no evidence of a global flood, and most scientists agree that such a ship and natural disaster would both be impossible.[4] Some researchers believe that a real (though localized) flood event in the Middle East could potentially have inspired the oral and later written narratives; a Persian Gulf flood, or a Black Sea Deluge 7,500 years ago has been proposed as such a historical candidate.[5][6]

Wikipedia also features more recent lists of deadly historic floods and fires, many of which are now considered to be largely attributable to climate change.

Wikipedia also provides some help describing event attributions to climate change:

Extreme event attribution, also known as attribution science, is a relatively new field of study in meteorology and climate science that tries to measure how ongoing climate change directly affects recent extreme weather events.[1][2][3][4] Attribution science aims to determine which such recent events can be explained by or linked to a warming atmosphere and are not simply due to natural variations.[5]

Attribution studies generally proceed in four steps: (1) measuring the magnitude and frequency of a given event based on observed data, (2) running computer models to compare with and verify observation data, (3) running the same models on a baseline “Earth” with no climate change, and (4) using statistics to analyze the differences between the second and third steps, thereby measuring the direct effect of climate change on the studied event.[5][6]

Heatwaves are the easiest weather events to attribute.[5]

Zubin Zeng wrote a related article last summer for the news site The Conversation: “Is climate change to blame for extreme weather events? Attribution science says yes, for some – here’s how it works.” (Retrieved 3 September 2021).

Meanwhile, the National Academy of Science created a lengthy report with a much more comprehensive description (2016). I am including some highlights below:

Definition:

Attribution: The process of evaluating the relative contributions of multiple causal factors to a change or an event with an assignment of statistical confidence (Hegerl et al., 2010).

From the Summary (I added the emphases):

The observed frequency, intensity, and duration of some extreme weather events have been changing as the climate system has warmed. Such changes in extreme weather events also have been simulated in climate models, and some of the reasons for them are well understood. For example, warming is expected to increase the likelihood of extremely hot days and nights (Figure S.1). Warming also is expected to lead to more evaporation that may exacerbate droughts and increased atmospheric moisture that can increase the frequency of heavy rainfall and snowfall events. The extent to which climate change influences an individual weather or climate event is more difficult to determine. It involves consideration of a host of possible natural and anthropogenic factors (e.g., large-scale circulation, internal modes of climate variability, anthropogenic climate change, aerosol effects) that combine to produce the specific conditions of an event. Extreme events are rare, meaning that typically there are only a few examples of past events at any given location.

Event attribution approaches can be generally divided into two classes: (1) those that rely on the observational record to determine the change in probability or magnitude of events, and (2) those that use model simulations to compare the manifestation of an event in a world with human-caused climate change to that in a world without. Most studies use both observations and models to some extent—for example, modeling studies will use observations to evaluate whether models reproduce the event of interest and whether the mechanisms involved correspond to observed mechanisms, and observational studies may rely on models for attribution of the observed changes.

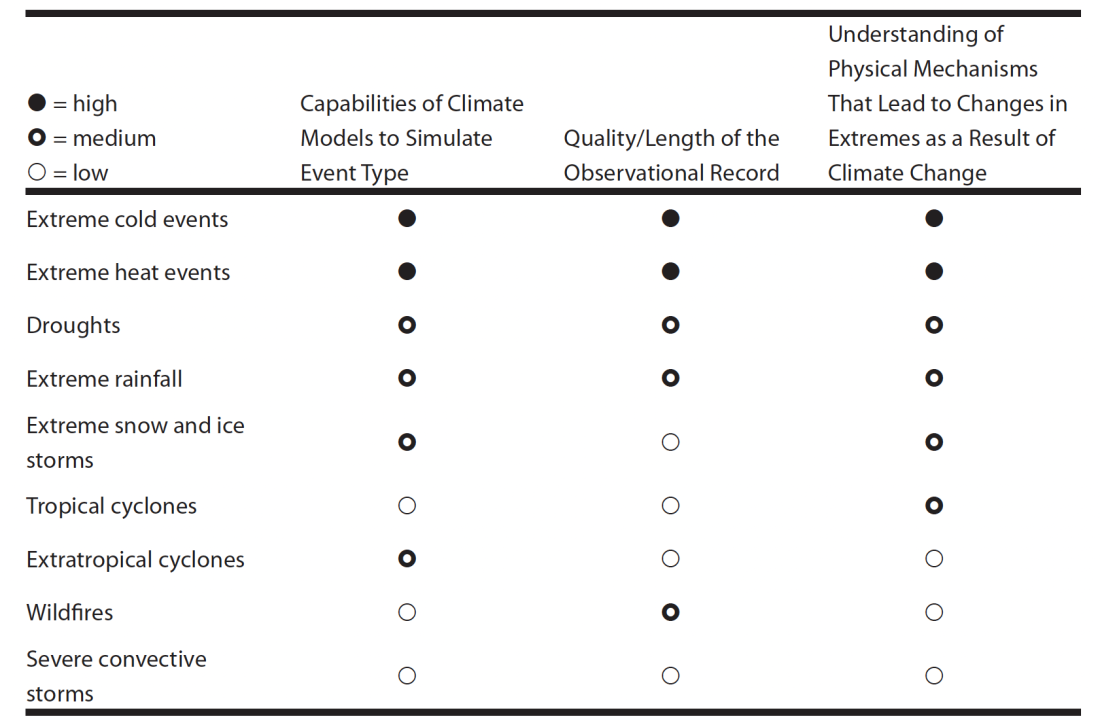

TABLE 5.1 This table… provides an overall assessment of the state of event attribution science for different event types. In each category of extreme event, the committee has provided an estimate of confidence (high, medium, and low) in the capabilities of climate models to simulate an event class, the quality and length of the observational record from a climate perspective, and an understanding of the physical mechanisms that lead to changes in extremes as a result of climate change. The entries in the table are based on the available literature and are the product of committee deliberation and judgment.

Next week’s blog will continue to discuss attributions, looking at specific cases. I will start by discussing the evidence for attributing anthropogenic (human) contributions to the global impact of climate change. I will further explore the methodology proposed by the National Academy, as discussed in this blog.

These floods should hopefully be enough of an eye-opener for the world to try to prepare for more floods in the future, if it’s a worst case scenario and climate change increases in the future, potentially causing more floods.

The huge impact of what happen to Pakistan has caught the worlds attention. The enormous flood that happened in Pakistan was the headlines for a couple of days. In addition to people losing their shelter. From the sea levels other countries might also experience this kind of attack.

Thanks.

Hi Professor, glad to see you’re still doing the blog. I was a student in one of your physics classes at Brooklyn College and wanted to say thank you for inspiring me.

What is happening in Pakistan has served as a wake-up call to the world. The disastrous flooding in Pakistan has been in the headlines for several days, with many people losing their houses and livestock, which for many people was a source of income. Because of the rapid rise in sea level, Pakistan will not be the first or only country to face this; other countries will follow if we do not begin to care for the earth.