The last two blogs tried to make the case that—without the full participation of developing countries—the energy transition away from fossil fuels is bound to fail. In the first of these two blogs (April 30th) I quoted two paragraphs from the long IEA (International Energy Agency) executive summary of the issue (Executive summary – Financing Clean Energy Transitions in Emerging and Developing Economies – Analysis – IEA). Last week’s report referred to an oil industry source that concluded that the world is short of necessary funding for the transition by 2 trillion US$, and will likely never be able to close the gap. The dependence of developing countries on rich countries to provide the financing for this transition should be viewed as an important trigger for a catastrophic failure to complete a global transition. One way to counter such failure and promote global resilience would be to minimize the cost needed for the transition. This blog is focused on such attempts.

I will start by quoting more from the same executive summary of the IEA report that was quoted in the April 30th blog, finishing with a summary of the case studies it has presented:

The transformation begins with reliable clean power, grids and efficiency…

Transforming the power sector and boosting investment in the efficient use of clean electricity are key pillars of sustainable development. Electricity consumption in emerging and developing economies is set to grow around three times the rate of advanced economies, and the low costs of wind and solar power, in particular, should make them the technologies of choice to meet rising demand if the infrastructure and regulatory frameworks are in place. Societies can reap multiple benefits from investment in clean power and modern digitalised electricity networks, as well as spending on energy efficiency and electrification via greener buildings, appliances and electric vehicles. These investments drive the largest share of the emissions reductions required over the next decade to meet international climate goals. Innovative mechanisms with international backing to refit, repurpose or retire existing coal plants are an essential component of power sector transformations.

Action on emissions in emerging and developing economies is very cost-effective

The average cost of reducing emissions in these economies is estimated to be around half the level in advanced economies. All countries need to bring down emissions, but clean energy investment in emerging and developing economies is a particularly cost-effective way to tackle climate change. The opportunity is underscored by the amount of new equipment and infrastructure that is being purchased or built. Where clean technologies are available and affordable – and financing options available – integrating sustainable, smart choices into new buildings, factories and vehicles from the outset is much easier than adapting or retrofitting at a later stage.

Transitions in the developing world must be built on access and affordability

Affordability is a key concern for consumers, while governments have to pursue multiple energy-related development goals, starting with universal energy access. There are almost 800 million people who do not have access to electricity today and 2.6 billion people who do not have access to clean cooking options. The vast majority of these people are in emerging and developing economies, and the pandemic has set back financing of projects to expand access. Efficiency is key to least-cost and sustainable outcomes. For example, meeting rising demand for cooling with highly efficient air conditioners will keep energy bills down for households – and minimise costs for the system as a whole. Action to provide clean cooking solutions and tackle other emissions will have major benefits for air quality: 15 of the 25 most polluted cities in the world are in emerging and developing economies, and air pollution is a major cause of premature death.

One obvious step to cost-effectively increase resilience is to be more strategic with resources. A good example could be undergrounding power lines (see September 5, 2023 blog). It is an expensive proposition and not every part of the grid needs the same protections. Parts that need better protections (hospitals, military facilities, campuses, etc.) can be served by smaller mobile grids (mini- or microgrids) that can get better protection and can work either on their own or connect to and disconnect from the main grid. The only difference between mini-grids and microgrids is their size, with no sharp line to distinguish between them.

Microgrids have been discussed throughout this blog. Just put the word into the search box for a refresher on my related posts. Here are a couple good places to start: the guest blog by Elisa Wood, titled “Microgrids” (May 6, 2014), and the blog titled “Microgrids – History is Catching Up” (April 29, 2014), about our film, “Quest for Energy,” which documents the microgrid that brought electricity to a small town in the Sundarbans region in India. The description of the film in that blog omits a personal note about something that took place during our travel, so I will add it here. During our two trips to India to make the film, my trip was divided into two parts; in the first part, my wife joined me as a “typical” American tourist and we visited many popular tourist destinations. In the second part of the trip, my wife returned home, and I proceeded to Kolkata to join the team that produced the film.

At the start of the first part of our first trip, we stayed in a hotel in Delhi. There were many other Americans in the hotel. During breakfast, an American lady asked me why we came to India. I described the film that we were about to produce to her; I still remember her reaction. My memory is not good enough for a direct quote but she looked at me with an approving look and spoke about a conspiracy theory with me. I still remember the Northeast blackout of 2003. One of the stories that spread around was that in certain neighborhoods (she specified which ones), people noticed a significant increase in pregnancies after the blackout. She gave me a half-smile and concluded that I was there to prevent people from “swamping the planet” with too many Indian babies. The fear of being “swamped” by the high fertility of developing countries was more common in the second half of the 20th century than it is now and was shared by many. It can be viewed as a predecessor of “replacement theory” (see my March 5, 2024 blog), which now dominates certain circles’ discussions of immigration policies.

Racism aside, the movie, “Quest for Energy,” showed the process of the globalization of electricity use (that I have described in previous blogs), which almost always proceeds through micro- and mini-grids. The newer aspect is the use of these facilities to enhance equity and resilience in both developed and developing countries on their ways to convert to “smart grids.” This is subject to extensive research that I will describe in future blogs.

This is obviously not the only cost-effective way to participate in the energy transition.

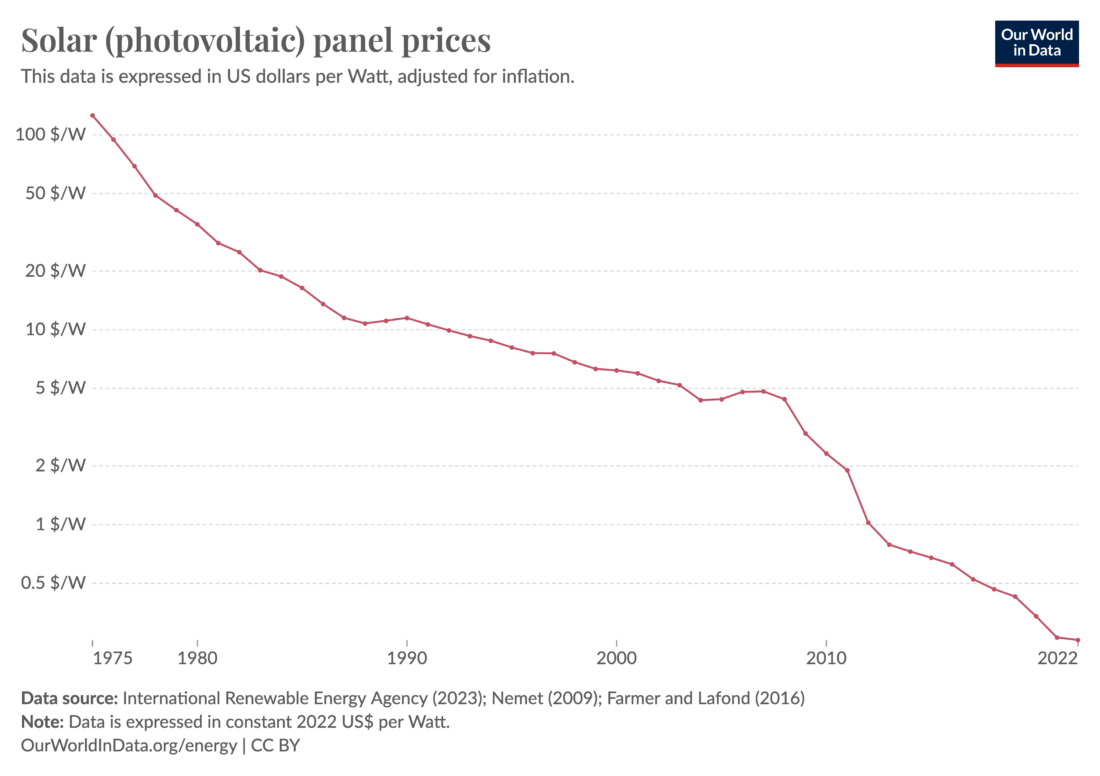

Throughout most of my scientific career, the dream of most scientists who have done research on solar cells was to be cost-competitive with fossil fuels. We have now reached that point. Solar and wind have become the dominant global primary energy sources; both are forms of solar energy (see November 5, 2019, blog). Figure 1 shows the changes in photovoltaic prices. Most of the declining prices are triggered by China’s efforts in this field. The recent drop into negative prices, shown in Figure 1, was discussed before (see June 9, 2020 blog); it indicates that supply is starting to exceed demand.

Figure 1 – Solar panel prices in US$/Watt (Source: Our World in Data)

Figure 1 – Solar panel prices in US$/Watt (Source: Our World in Data)

The Chinese continue to dominate production of solar panels; this is already triggering tariffs in various quarters, which are not helpful for the global energy transition.

However, the global energy transition is still highly dependent on local politics. The political situation in the US resembles 2016 (see the December 18, 2018 blog). Perhaps the most consequential international agreement on how to proceed with the global energy transition was the Paris Agreement, which was signed in December 2015. The following year, Ex-President Trump was elected to the presidency. One of his first actions was to take the US out of this agreement, an action that slowed down the transition considerably. This year, former president Trump is again the leading Republican candidate, with a considerable chance of succeeding. If he becomes president again, there is no reason to believe that he will act differently. Next week I will focus on the US government’s role in the transition—specifically, the activities most sensitive to changes in political power.