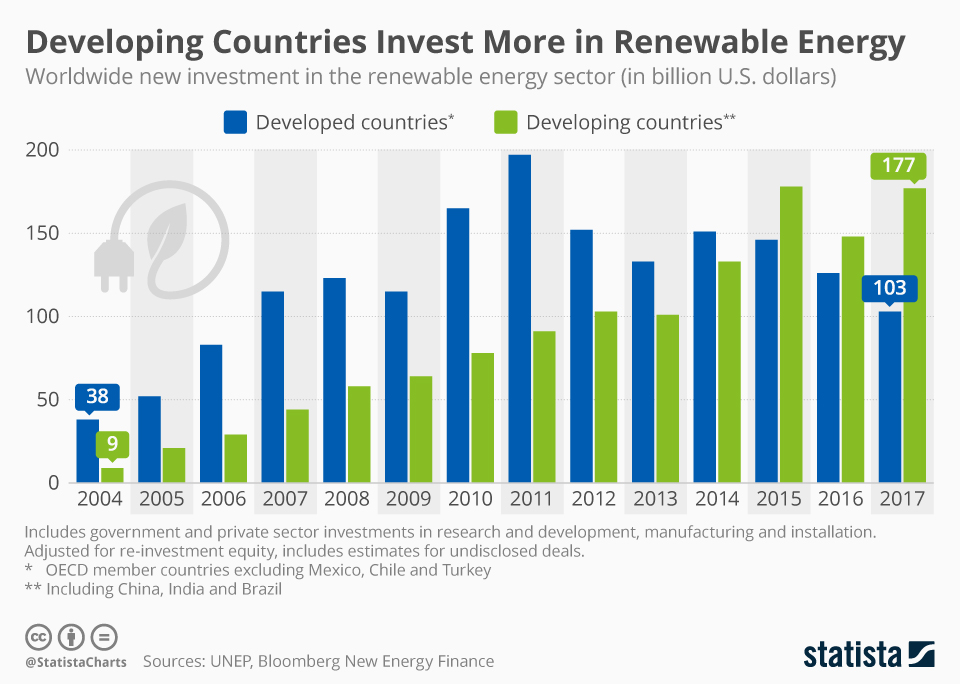

As was shown in a previous blog, the global spread of electricity is a recent phenomenon that took place in the second half of the last century and the beginning of this century. In approximately the same time span, the world has started to realize that we need to replace fossil fuels as the primary energy source that drives our energy needs. This is a costly transition. Figure 1 shows that in terms of new investments, developing countries are doing a better job than developed countries. Considering the fact that the nominal GDP/capita of developed countries can be more than 30 times higher than that of developing countries, the question is how they do it. This blog will focus on the equity part, while next week’s blog will focus on the resilience part of the same issue.

Figure 1 – Developing countries invest more in renewable energy (Source: Statista)

Figure 1 – Developing countries invest more in renewable energy (Source: Statista)

I was fortunate to observe a small part of both electrification and energy transitions. As I mentioned in some previous blogs (see February 24, 2015), more than fifteen years ago, I worked with a group of friends on a film about a society in a remote part of a developing country (India) as it transitioned from a mainly hunter-gatherer existence to an electricity-driven, modern civilization. The result was a series of short documentaries, including: “Quest for Light,” “Quest for Energy,” and “Beyond the Grid” (see April 29, 2014). When we produced the films, people told us how much they paid for the new electricity. It turned out that they paid considerably higher prices than people on the “mainland.” One of the reasons for this discrepancy was that most of the electricity that was generated on the mainland was produced using coal as the primary energy source, while electricity that was generated in Gosaba (this small town in the Sundarbans region, see the original blog or the movie) came from burning trees from the mangrove forest nearby and planting new trees to compensate. When we asked the people if they didn’t mind paying more, the unanimous answer was that they saw Bangladesh across the Bay of Bengal and they knew the impact of relying on coal, including catastrophic consequences on their weather. They understood that they could not rely on coal burning for generating new electricity. The filming was done 15 years ago.

Today Colombia, another developing country (2022 GDP/Capita $6,624) is introducing the following new plan to finance its electricity generation:

BOGOTÁ, Colombia (AP) — Colombia’s government on Tuesday rolled out new incentives to reduce electricity consumption in the South American nation, which has been hit by a severe drought that has diminished the capacity of local hydroelectric plants and brought officials close to imposing power cuts.

The ministry of mines and energy said that in the following weeks homes and businesses that exceed their average monthly electrical consumption will be charged additional fees for every extra kilowatt-hour used, while those who use less electricity than usual will be rewarded with discounts.

To put a broader perspective on the issue, it became a focal point of a global efforts in the yearly COP (Conference of Parties) effort to mitigate and adapt to climate change. Facilitating global agreement to transfer resources to help developing countries in the energy transition became a key condition for these countries’ full participation. Global energy transition away from fossil fuel is impossible without participation of developing countries. Specifically, this issue was the focal point of COP27, which was discussed in a previous blog (November 29, 2022):

UN Climate Change News, 20 November 2022 – The United Nations Climate Change Conference COP27 closed today with a breakthrough agreement to provide “loss and damage” funding for vulnerable countries hit hard by climate disasters.

As is described here, the all-important implementation of this agreement has been deferred until COP28, with the meeting of an established “transitional committee” to happen no later than March 2023. We obviously will return to this issue.

Last year, Muhammad Siddiqui, a Pakistani student of mine, wrote a guest blog (January 3, 2023), “Guest Blog: Loss & Damage Funds and the Developing Indian Subcontinent.”

In 1985, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) issued a short report on this issue and in 2021 the International Energy Agency (IEA) issued its latest report. The IEA report is long; the table of contents is shown below:

1.0 Executive summary

2.0 Setting the scene

3.0 The landscape for clean energy finance in EMDEs

4.0 Financing clean power, efficiency and electrification

5.0 Financing transitions in fuels and emissions-intensive sectors

The executive summary alone includes more than 20 paragraphs, from which I will only cite the following:

Emerging and developing economies are set to account for the bulk of emissions growth in the coming decades unless much stronger action is taken to transform their energy systems. With the exception of parts of the Middle East and Eastern Europe, their per capita emissions are among the lowest in the world – one-quarter of the level in advanced economies. In a scenario reflecting today’s announced and existing policies, emissions from emerging and developing economies are projected to grow by 5 gigatonnes (Gt) over the next two decades. In contrast, they are projected to fall by 2 Gt in advanced economies and to plateau in China.

But a massive surge in clean energy investment in the developing world can put emissions on a different course

An unprecedented increase in clean energy spending is required to put countries on a pathway towards net-zero emissions. Clean energy investment in emerging and developing economies declined by 8% to less than USD 150 billion in 2020, with only a slight rebound expected in 2021. By the end of the 2020s, annual capital spending on clean energy in these economies needs to expand by more than seven times, to above USD 1 trillion, in order to put the world on track to reach net-zero emissions by 2050. Such a surge can bring major economic and societal benefits, but it will require far-reaching efforts to improve the domestic environment for clean energy investment within these countries – in combination with international efforts to accelerate inflows of capital.

I strongly recommend that all of us read and try to act on the full report.