July 4th, this year, marks the 250th birthday of the US. I will return to this issue repeatedly in the coming year. This blog and the next few, will focus on energy. This week’s focus is the connection between energy use and climate change. Just for “fun,” you can put “rnergy use and climate change” into the search box and see how the computer includes almost every blog that I have written since April 22, 2012. However, if you instead search for “energy-mass equivalence,” you will get only the blog from July 9, 2013, which directly discusses the equivalence through the most broadly used physics equation, shown below:

- E = MC2

E is the energy, M is the mass, and C is the speed of light in a vacuum. Basically, what the equation is telling us is that in one form or another, all the “stuff” in the universe is energy. As far as we know, the only planet that can comprehend all of this is ours. When, during the 18th – 19th centuries, some on our planet found that a shift from an agrarian to an industrial economy (Industrial Revolution) would better their lives, it had major consequences on many activities. One of the most important transitions of the Industrial Revolution was the start of the shift toward fossil fuels as energy sources. Now, we are in the middle of the next shift in energy sources. This shift is currently experiencing changes in leadership that we will start to examine in this blog. We will continue to examine the implications of this energy shift in areas such as financing, innovations, and developing countries, in the next few blogs.

Until recently, the use of fossil fuels was directly correlated with economic progress. The relationship between the two is called energy intensity. This topic was discussed in an earlier blog (December 20, 2022) and in last week’s blog. Figure 1 from last week’s blog shows the recent emerging separation between carbon dioxide emissions and economic growth in six places: the US, four European countries, and the European Union as a bloc. There are others, but all are developed countries; China is not among the list yet. This blog is focused on the shift in the leadership in energy use from the US to China. bbbnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnn

The AI summary below starts by addressing why China cannot, yet, be characterized as a country that separates carbon emissions from economic growth. It continues with data about China taking the leadership role from the US in replacing fossil fuels with sustainable energy sources:

AI Through Google:

China has demonstrated a “weak decoupling” of carbon emissions from its GDP growth: its economy has grown faster than its carbon emissions. In fact, recent data indicates that national carbon emissions have plateaued or experienced slight declines, even as GDP has increased, suggesting an emerging stronger separation.

Decoupling Status

-

-

- Weak Decoupling:From 1990 to 2020, China’s real GDP increased by over 14 times, while energy-related CO2 emissions increased by approximately four times. This indicates that economic growth has consistently outpaced the growth of emissions, thus achieving a state of weak decoupling at the national level.

- Progressive Decoupling:In the period from 2012 to 2017, the annual growth rate of emissions decelerated significantly (from 10% to 0.3%) due to gains in energy efficiency and a change in consumption patterns, even as the economy continued to grow.

- Emerging Strong Decoupling:Recent analyses (from early 2024 through Q3 2025) suggest that China’s CO2 emissions have plateaued or slightly fallen for 18 consecutive months, a trend driven by a record surge in clean energy adoption (solar, wind, electric vehicles). This is a potential shift towards strong decoupling, where absolute emissions decrease while the economy expands.

-

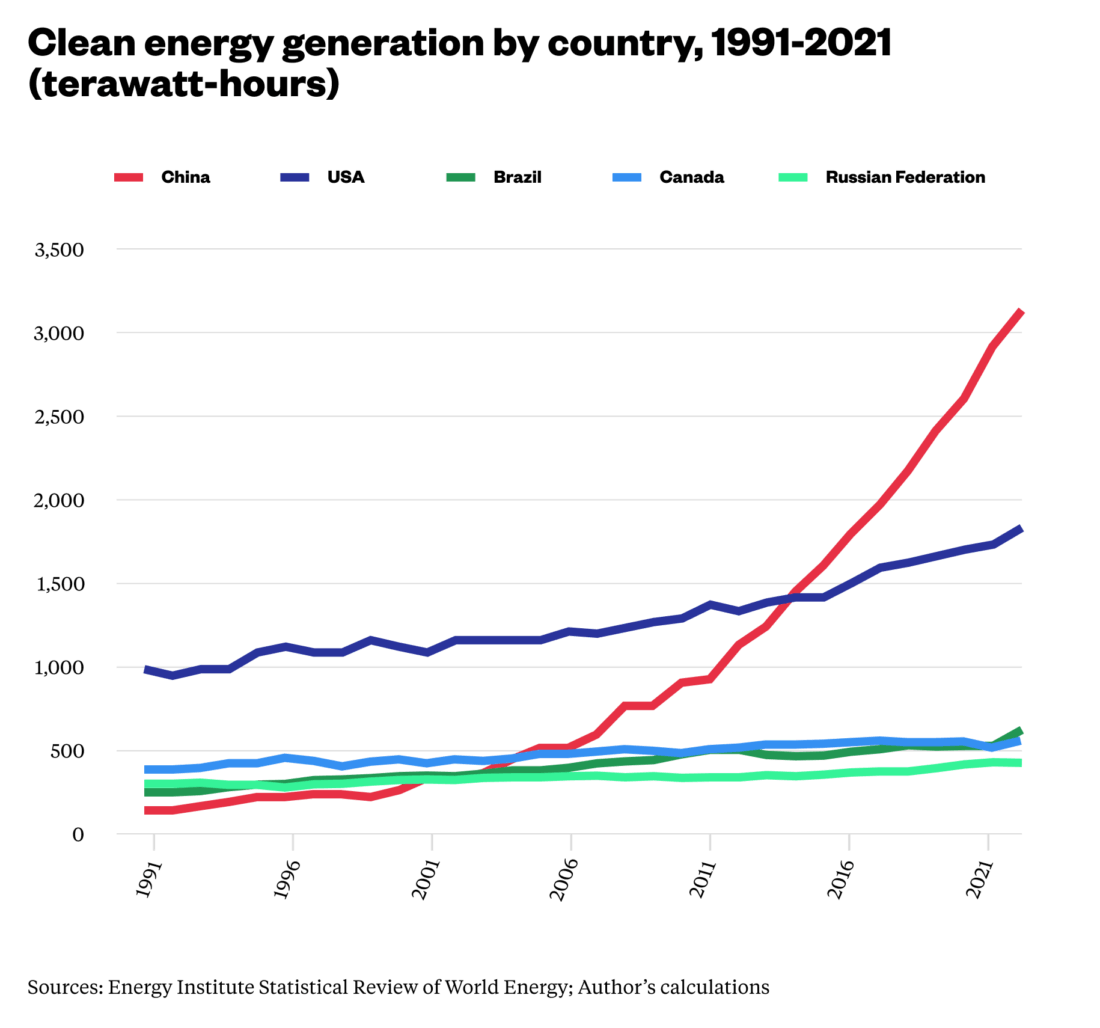

Figure 1 clearly shows the change in countries leading the transition towards electricity powered by clean energy production. According to the graph, China surpassed the US in clean energy generation around 2013 and has continued this trend at a much higher rate than US production.

Figure 1- Clean energy generation by country, 1991-2021

Figure 1- Clean energy generation by country, 1991-2021

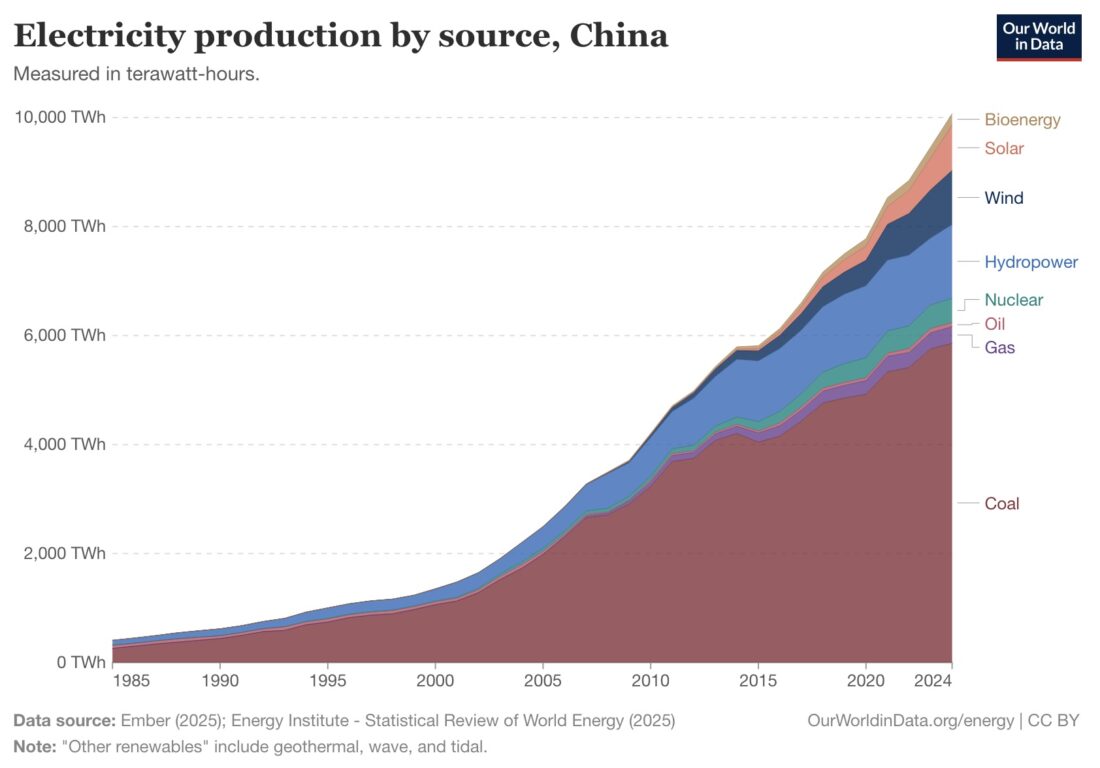

However, Figure 2 shows that China’s electricity production is still heavily dependent on coal, the dirtiest of fossil fuels.

Figure 2 – Graph of China’s electricity production by source, 1985-2024

Figure 2 – Graph of China’s electricity production by source, 1985-2024

(By Hannah Ritchie and Max Roser – Hannah Ritchie and Max Roser (2020) – “Energy”. Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Retrieved from: ‘https://ourworldindata.org/energy [Online Resource], CC BY 4.0, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Electricity_sector_in_China#)

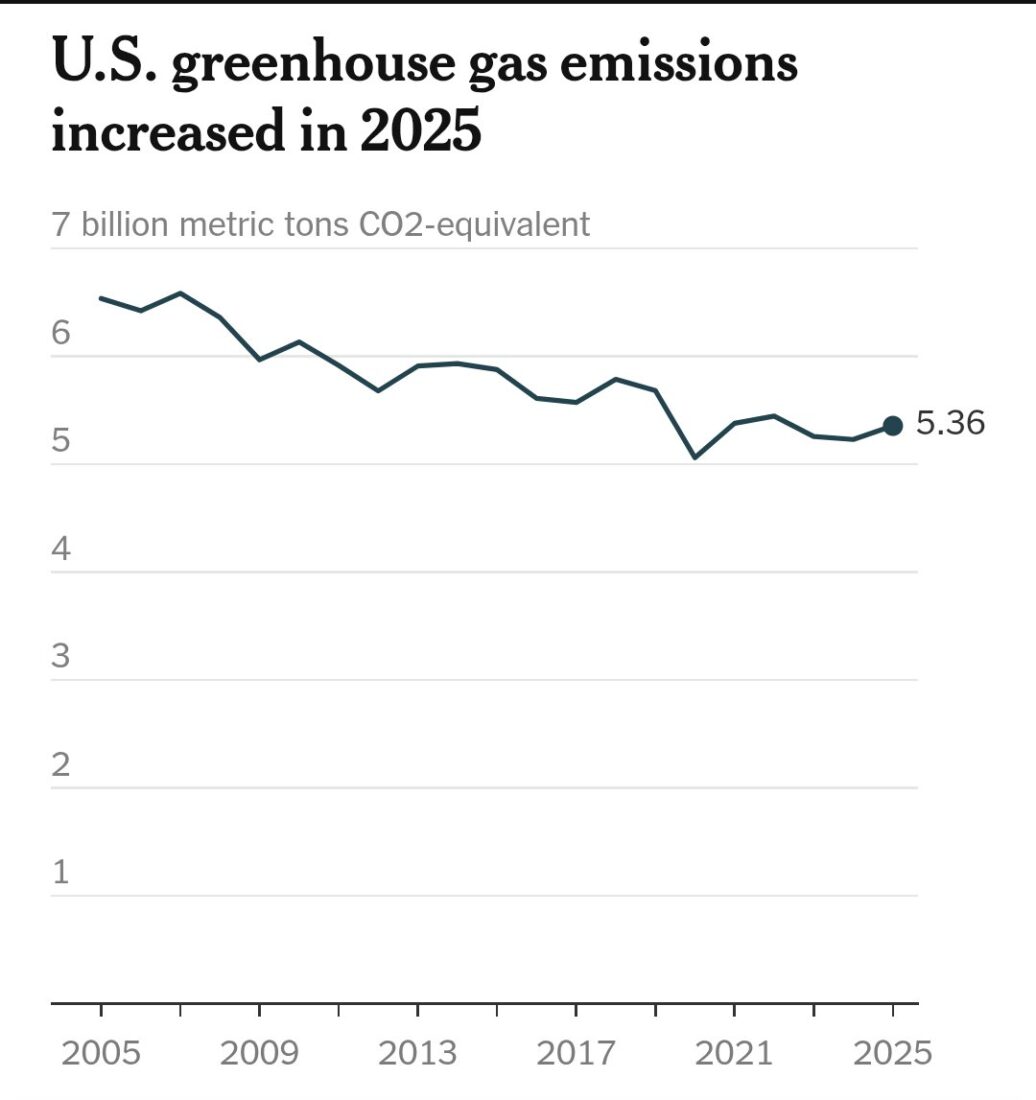

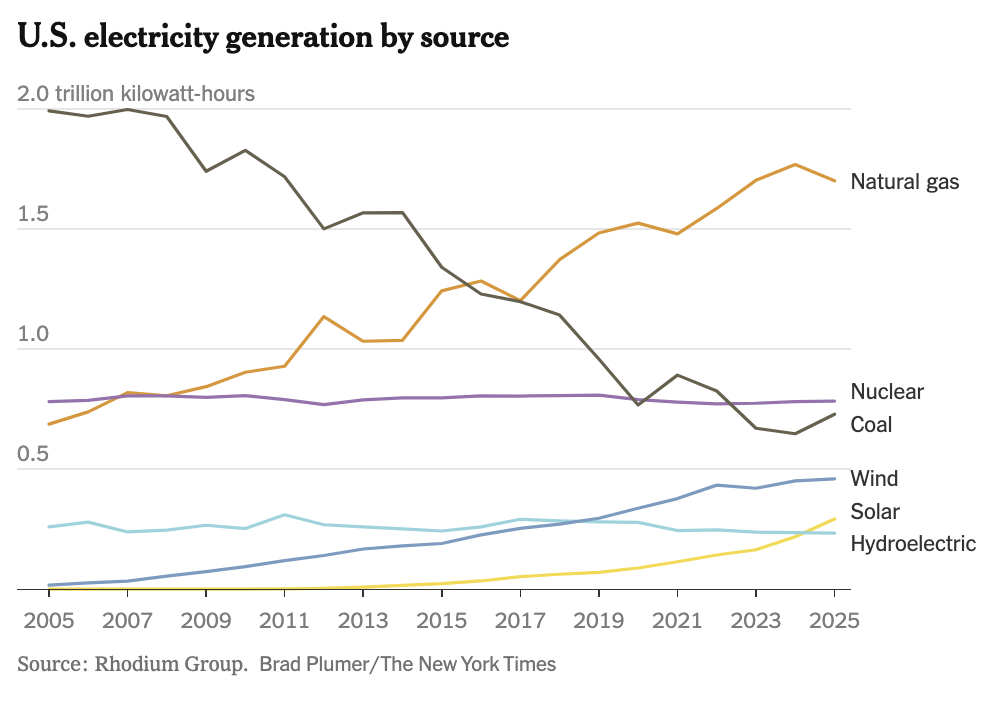

Meanwhile, Figures 3 and 4 show what seems to be a different story. The greenhouse gas emissions and the coal used by the US to generate electricity are in clear decline over the last 20 years. This is an apparent strengthening of the argument that was made in last week’s blog that, in spite of President Trump’s unchanging negative opinion about the energy transition in his first term, the US shift to sustainable energy has been resilient to his attitude. However, the argument goes, he learned from his “mistakes” in his first term to make the second term more effective. I mentioned in earlier blogs that the energy picture for 2025, the start of President Trump’s second term, are not yet fully available. However, Figures 3 and 4 are extended to include 2025. You’d need a magnifying glass to deduce the trend to 2025 but both figures show a small increase. To decide whether the small increase is “noise” in the data or the start of a new trend, one needs to wait!

Figure 3 – US greenhouse gas emissions, 2005-2025 (Source: NYT: U.S. Emissions Jumped in 2025 as Coal Power Rebounded)

Figure 4 – US electricity generation by source, 2005-2025 (Source: NYT: U.S. Emissions Jumped in 2025 as Coal Power Rebounded)

Figure 4 – US electricity generation by source, 2005-2025 (Source: NYT: U.S. Emissions Jumped in 2025 as Coal Power Rebounded)

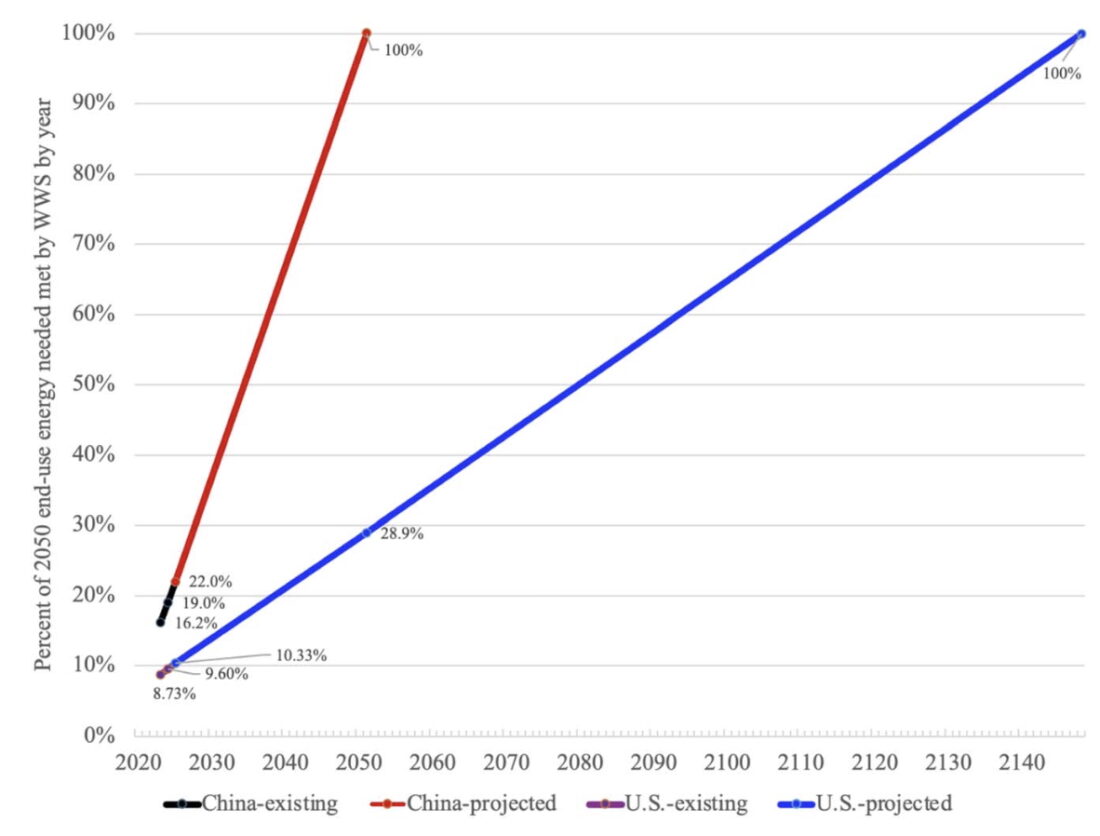

In the meantime, Figure 5 strengthens the argument of leadership change by estimating the deadline for complete energy transition to sustainable energy. PV Magazine summarizes this argument with the following short paragraphs:

The United States could nearly eliminate its carbon emissions and air pollution by 2148 if it maintained a pace of adding 43 GW of renewables per year, set during the first seven months of 2025, and achieved “near-electrification” of each energy-using sector.

Stanford University Prof. Mark Jacobson presented that finding and results for 149 other countries in a research paper that was recently published in RSC Sustainability.

The “most substantial and encouraging finding,” Jacobson said, is the “rate by which China is transitioning its energy economy.”

China, which added renewable generating capacity at an annual pace of 397 GW during the first 10 months of 2025, could at that pace eliminate carbon emissions and air pollution by 2051 with near-electrification of all energy sectors.

Figure 5 – Rate of energy transition, China vs. US, existing vs. projected (source: PV Magazine)

Figure 5 – Rate of energy transition, China vs. US, existing vs. projected (source: PV Magazine)

An article in Nature summarizes the backsliding argument:

Although climate action is undermined by political interests and institutional inertia, multiple safeguards are in place to prevent backsliding on progress so far, and positive feedbacks reinforce progress despite opposing forces. Key elements of climate action are irreversible and can be further strengthened by commitments, investments and positive narratives.

There is a growing political divide with forces at work, such as the deliberate efforts by the current US administration to weaken climate policies, discredit climate science and promote fossil fuels, which is cause for concern. This creates uncertainty in the direction of long-term policy to tackle climate change, which undermines the investments needed to drive decarbonization. Nevertheless, ambitious climate action is well underway and continues to evolve under the auspices of the Paris Agreement. Policies and investments have driven rapid cost reductions in renewable energy and batteries, while expanding the deployment of a range of low-carbon technologies.

China is continuing to accelerate the transition, both in research and data gathering:

China’s Ministry of Finance, alongside several other of the country’s ministries, central bank, and regulators, announced the release of its new “Corporate Sustainable Disclosure Standard No. 1 – Climate (Trial),” a new standard, aligned with the IFRS Foundation’s climate reporting standard, aimed at enabling companies to report on climate-related risks, opportunities and impacts, and to support China’s green development goals.

According to the ministry, the new trial climate reporting standard forms part of China’s efforts to addressing climate change and accelerating its comprehensive green economic and social development transformation, by providing a key mechanism to enable green and low-carbon development, as well as to solve greenwashing problems through the standardization of information disclosure, and support the guidance of capital flows to low-carbon projects.

The country also seems to be overproducing and reducing the prices of solar cells:

In a factory in a smoggy corner of China’s inland Shaanxi province, the country’s world-leading solar industry is on display. Robots scoot around carrying square slices of polysilicon, a substance usually made from quartz. The slices, each 180mm across and a hair’s breadth thick, are called wafers. They are bathed in chemicals, shot with lasers and etched with silver. All that turns them into solar cells, which convert sunlight into electricity. Several dozen of these cells are then bundled together into a solar module. The factory, which is owned by LONGi Green Energy Technology, a giant of solar manufacturing, can churn out about 16m cells a day.

China’s solar industry is dominant across every stage of the global supply chain, from the polysilicon to the finished product. Module production capacity in the country reached roughly 1,000 gigawatts (GW) last year, almost five times that of the rest of the world combined, according to Wood Mackenzie, a consultancy. What is more, it has tripled since 2021, outgrowing the rest of the world, despite efforts by America and others to boost domestic production. China is now able to produce more than twice as many solar modules as the world installs each year.

Meanwhile, under Trump, the US is continuing to test the resilience of the shift toward renewable energy:

By pulling the United States out of the main international climate treaty, seizing Venezuelan crude oil and using government power to resuscitate the domestic coal industry while choking off clean energy, the Trump administration is not just ignoring climate change, it is likely making the problem worse.

President Trump has never been shy about rejecting the scientific reality of global warming: It’s a “hoax,” he has said, a “scam,” and a “con job.”

In recent days his administration has slammed the door on every possible avenue of global cooperation on the environment. At the same time, it is sending the message that it wants the world to be awash in fossil fuels sold by America, no matter the consequences. The moves follow one of the hottest years on record, during which scientists say climate change supercharged raging wildfires in Los Angeles, deadly flooding in Texas, and a Category 5 hurricane that ravaged Caribbean islands.

I will continue to follow the dynamics.