The German Renewable Energy Act (German: Erneuerbare-Energien-Gesetz, EEG) was designed to encourage cost reductions based on improved energy efficiency from economies of scale over time. The Act came into force in the year 2000 and was the initial spark behind a tremendous boost of renewable energies in Germany.

The three main principles of the EEG are:

a) Investment protection through guaranteed feed-in tariffs and connection requirement: Originally, every kilowatt-hour generated from renewable energy facilities received a fixed feed-in tariff. The system has recently been modified to now also include a market premium system. Network operators are required to preferentially feed-in this electricity into the grid over electricity from conventional sources (nuclear power, coal and gas). Renewable energy plant operators in principle receive a 20-year, technology-specific, guaranteed payment for their electricity generation. Small and medium enterprises have been given new access to the electricity market, along with private land owners. The Federal Ministry for Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety argued that anyone producing renewable energy could sell his ‘product’ for a 20-year fixed price.

b) No charge to Germany’s public purse: The promotion of renewable electricity continues to be necessary up until now. The EEG rates of remuneration show what electricity from wind, hydro, solar, bio- and geothermal energy actually cost. Compared to fossil fuels, there are lower or no external costs, such as damage to the environment, the climate or human health. The remuneration rates have until recently been considered not to be subsidies as such, since they are not paid for by taxes and are paid for by every consumer as an EEG surcharge (EEG-Umlage) that is included in the electricity bill. The polluter pays principle a.k.a “whoever consumes more, pays more” is in effect passed on to consumers. In 2013, the total EEG surcharge amounted to EUR 20.4 billion. In 2014, the EEG surcharge was set at 6.24 ct/kWh. Certain reductions of the EEG surcharge apply for energiy intensive industries (so-called special equalisation scheme).

c) Innovation by decreasing feed-in-tariffs: Feed-in tariffs in Germany decrease in regular intervals to exert cost pressure on energy generators and technology manufacturers. The decrease (called “degression”) applies to new plants. Thus, it is hoped, technologies are becoming more efficient and less costly.

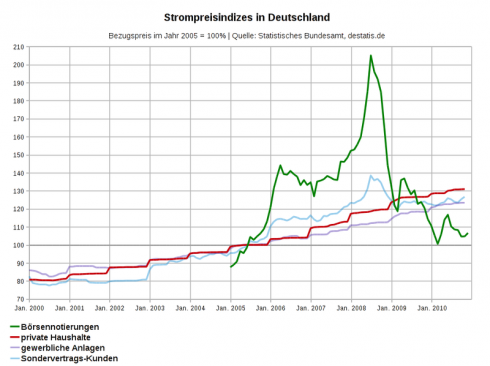

The prices of electricity over this time period behaved as the figure below shows:

Figure 1 – electricity prices in Germany since the EEG was introduced. The green line above is the price of electricity on the German electricity exchange. The red line is the average price of electricity for households. The other lines are for commercial clients and special customers (notably, their prices have also risen).

The price of electricity in Germany was high relative to other countries, as can be seen in Figure 3.

As I mentioned in last week’s blog, more than 60% of the Germans were happy with the new energy policy. This, of course, leaves plenty of unhappy people. Any transition of this magnitude produces many winners and losers. They, in turn, keep the conversation going and serve as an excellent example for other countries, who can take notice, learn and adapt – thus pushing forward the global energy transition that will mitigate destructive changes in the physical environment.

Of the many aspects mentioned above, the feed-in tariff is key. Since its inception, some important changes have taken place, including:

-

Purchase prices were based on generation cost. This led to different prices for wind power, solar power, biomass/biogas and geothermal and for projects of different sizes.

-

Purchase guarantees were extended to 20 years.

-

Utilities were allowed to participate.

-

Rates were designed to decline annually based on expected cost reductions, known as “tariff degression”.

Since it was the most successful, the German policy (amended in 2004 and 2008) often was the benchmark against which other feed-in tariff policies were considered.

Other countries followed the German approach. Long-term contracts are typically offered in a non-discriminatory manner to all renewable energy producers. Because purchase prices are based on costs, efficiently operated projects yield a reasonable rate of return.

This principle was stated as:

‘The compensation rates…have been determined by means of scientific studies, subject to the proviso that the rates identified should make it possible for an installation – when managed efficiently – to be operated cost-effectively, based on the use of state-of-the-art technology and depending on the renewable energy sources naturally available in a given geographical environment.’

—2000 RES Act

Feed-in tariff policies typically target a 5–10% return.

Feed-in tariffs (REFIT) supported growth in solar power in Spain, Germany and wind power in Denmark.

The success of photovoltaics in Germany resulted in an electricity price drop of up to 40% during peak output times, with savings between €520 million and 840 million for consumers. Savings for consumers have meant conversely reductions in the profit margin of big electric power companies, who reacted by lobbying the German government, which reduced subsidies in 2012. Energy utilities lobbied for the abolition, or against the introduction, of feed-in tariffs in other parts of the world, including Australia and California. Increase in the solar energy share in Germany also had the effect of closing gas- and coal-fired generation plants.

Some of the important losers over the years were the German utilities. An article by Leon Mangasarian and Stefan Nicola from Bloomberg that was published in Renewable Energy World summarized some of the important issues that they were facing. I am including few paragraphs below:

BERLIN — Germany’s biggest utilities face dwindling market shares as the shift to renewable energy spurs regional power generation and storage technology, a senior member of Chancellor Angela Merkel’s party said.

Electricity companies are ‘fighting something of their last stand,’ Christine Lieberknecht, the Christian Democratic Union premier of Thuringia state, said in an interview. ‘In a few years, nobody will even talk about it anymore because the technology for decentralization of power production and energy self-determination will make such strides.’

That vista suggests a deepening crisis for EON SE and RWE AG, Germany’s biggest utilities, whose profits are slumping as Merkel pushes plans to close all 17 German nuclear reactors by 2022 in response to the Fukushima meltdown in Japan in 2011. Both companies produce mostly conventional energy.

Germany’s energy landscape is shifting as renewable sources grab revenue while consumers and companies criticize rising power costs that are three times higher than in the U.S., in part due to taxes and subsidies to promote renewable energy. Merkel plans to more than triple Germany’s renewable share to 80 percent by 2050 from about a quarter now.

Essen-based RWE generated 6.4 percent of its power from alternative energy sources last year, compared with almost double that at Dusseldorf-based EON, Germany’s biggest utility by market capitalization.

As mentioned earlier, the feed-in tariff is destroying the business model of the electric utilities and serves also as a vehicle to subsidize the alternative energy producers. This will be further explored in the next blog, where I will shift to the producers.

In my last blog, I ended with a look at one at of the most fascinating recent developments of the German adaptations to these change – the splitting of the largest utility, E.ON into two companies. One of these will continue to be focused on fossil fuels while the other one will completely shift to the new alternative energies and integrating consumer demands with energy supply. This will be fascinating to watch and, if successful, could be a great basis for all of us to learn from.