Figure 1 – Taken from the 2017 Intelligence Report

Figure 1 – Taken from the 2017 Intelligence Report

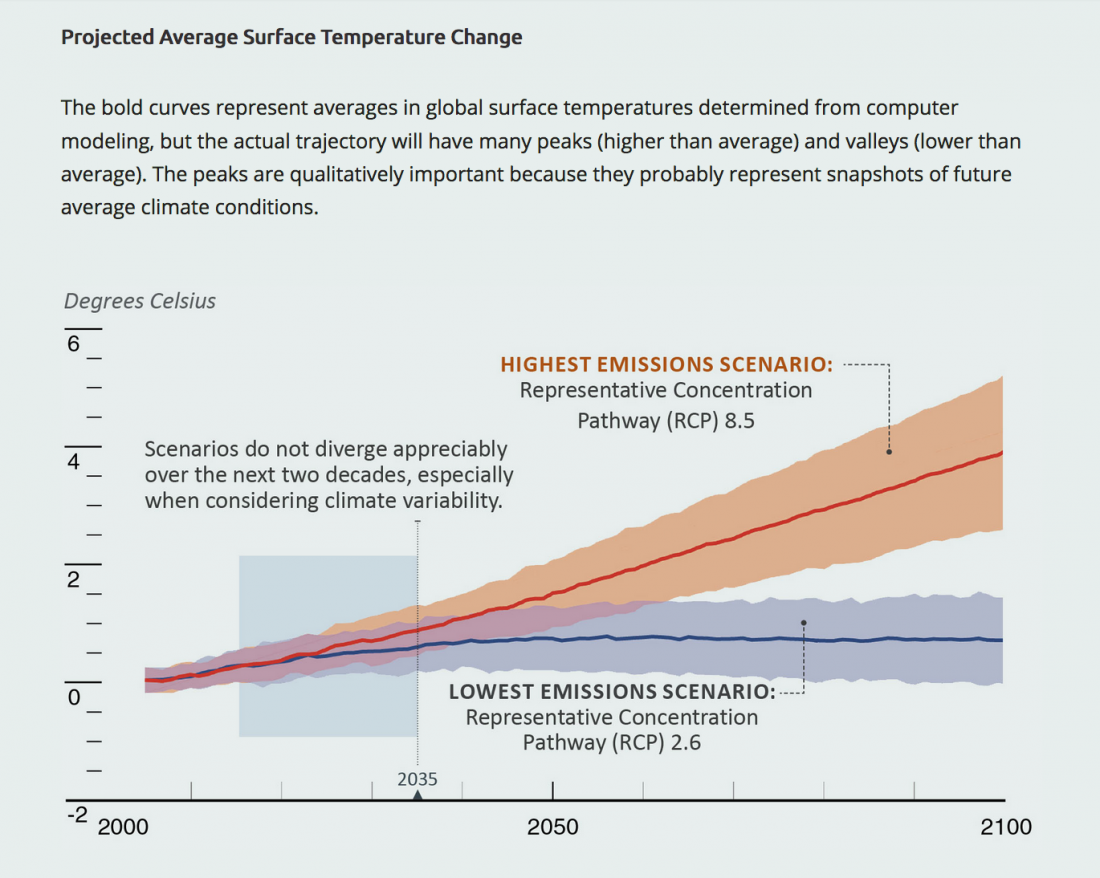

Figure 1 might look familiar – I took it from the fifth IPCC report (AR5) and showed it in my October 28, 2014 blog where I discussed the IPCC’s use of scenarios. This time, I found the figure in the recent US intelligence report, “Global Trends: Paradox of Progress.” The report was presented in January 2017, about two months after the election of President Trump (the exact date was not given so I cannot tell if by the time of publication President Trump was president elect or had taken office). “Global Trends” is a series of unclassified reports that the US intelligence community issues about the way that they see the near and intermediate future of the US – specifically how the US will function in a changing world. They issue these reports once every four years. I am using them in an effort to teach students how to model the future based on information gathered about the recent past. Versions of them are presented to Congress; in a sense, I view them as the official perspective of the US government and as such, very significant. I have no idea, however, if the president is required to read them.

The intelligence community is using Figure 1 to introduce the dangers associated with global climate change. They have provided their own explanations for the figure, apart from those that the IPCC gave. Not surprisingly, the 2017 report is going through some “modifications” as the Trump presidency progresses. These changes are interesting and I will devote next week’s blog to some of them; fortunately, at no point do they present climate change as a “Chinese Hoax.”

I want to emphasize the large bands that engulf the two main trends. These two bands represent the uncertainty in these predictions. They result not from uncertainty about the science or the human contributions to climate change but rather from the realization that we don’t yet have a full understanding of the feedback mechanism that changes the temperature equilibrium as a result of changes the chemistry of the atmosphere. The most important feedback mechanism that contributes to the climate change and is not yet fully understood is the role of clouds in the process. Other, better-understood feedback mechanisms include how the melting of snow and ice – especially in the Polar Regions – changes the surface reflectivity; how the melting of frozen tundra releases carbon greenhouse gases; the oceans’ ability to absorb such greenhouse gases; and the changing of the atmosphere’s ability to absorb water vapor. The solid lines in the middle of each uncertainty band represent the working number that is needed for any planning required to meet the dangers of global climate change that include policies targeted at mitigation and adaptation. These projections use specific scenarios to minimize the uncertainty inherent in trying to predict future levels of emissions. Yet climate change deniers have presented these uncertainties either as proof that scientists are ignoramuses who don’t know what they are talking about – and are just interested in increasing their grant money – or that this is an international conspiracy to damage the US economy.

In this day and age, The New York Times has decided that its editorial page is not balanced enough. So they hired Bret Stephens to establish balance. The rest of this blog is dedicated to this effort.

Here is a very short description of Stephens’ background as taken from Wikipedia:

Bret Louis Stephens is a neoconservative American journalist who won a Pulitzer Prize for commentary in 2013. Stephens began working as a columnist at The New York Times in late April 2017

James Bennet from The New York Times introduced Bret Stephens in an Op-Ed column:

I wanted to call your attention to our new columnist, Bret Stephens, whose first piece appears today. Bret, the winner of the 2013 Pulitzer Prize for commentary, has joined us from The Wall Street Journal, where he wrote the Global View column and also served as deputy editorial page editor.

For a sense of how Bret thinks about his role you might consider his response while at the Journal to criticism he received for opposing Donald Trump. He wrote, in part, “What a columnist owes his readers isn’t a bid for their constant agreement. It’s independent judgment. Opinion journalism is still journalism, not agitprop. The elision of that distinction and the rise of malevolent propaganda outfits such as Breitbart News is one of the most baleful trends of modern life. Serious columnists must resist it.”

Well, in spite of his lack of any related credentials, Mr. Stephens decided that his “virgin” contribution to this vaunted balance would be dedicated to climate change. For obvious reasons, his contribution attracted very broad attention. To avoid any argument that I am cherry picking his arguments and missing the message, I am posting excerpts from his column below.

These selected excerpts make up the majority of this week’s blog because, as always, details make a difference and given that there’s been three weeks’ time delay between the original NYT paper and the posting of the blog, it’s much harder for my readers to locate:

There’s a lesson here. We live in a world in which data convey authority. But authority has a way of descending to certitude, and certitude begets hubris. From Robert McNamara to Lehman Brothers to Stronger Together, cautionary tales abound.

We ought to know this by now, but we don’t. Instead, we respond to the inherent uncertainties of data by adding more data without revisiting our assumptions, creating an impression of certainty that can be lulling, misleading and often dangerous

Why? The science is settled. The threat is clear. Isn’t this one instance, at least, where 100 percent of the truth resides on one side of the argument?

Well, not entirely. As Andrew Revkin wrote last year about his storied career as an environmental reporter at The Times, “I saw a widening gap between what scientists had been learning about global warming and what advocates were claiming as they pushed ever harder to pass climate legislation.” The science was generally scrupulous. The boosters who claimed its authority weren’t.

Anyone who has read the 2014 report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change knows that, while the modest (0.85 degrees Celsius, or about 1.5 degrees Fahrenheit) warming of the earth since 1880 is indisputable, as is the human influence on that warming, much else that passes as accepted fact is really a matter of probabilities. That’s especially true of the sophisticated but fallible models and simulations by which scientists attempt to peer into the climate future. To say this isn’t to deny science. It’s to acknowledge it honestly.

Let me put it another way. Claiming total certainty about the science traduces the spirit of science and creates openings for doubt whenever a climate claim proves wrong. Demanding abrupt and expensive changes in public policy raises fair questions about ideological intentions. Censoriously asserting one’s moral superiority and treating skeptics as imbeciles and deplorables wins few converts.

None of this is to deny climate change or the possible severity of its consequences. But ordinary citizens also have a right to be skeptical of an overweening scientism. They know — as all environmentalists should — that history is littered with the human wreckage of scientific errors married to political power.

I’ve taken the epigraph for this column from the Polish poet Czeslaw Milosz, who knew something about the evils of certitude. Perhaps if there had been less certitude and more second-guessing in Clinton’s campaign, she’d be president. Perhaps if there were less certitude about our climate future, more Americans would be interested in having a reasoned conversation about it.

By the time that I am writing this blog, 1551 NYT readers have commented on his piece. I am attaching three of the first comments that provide the anti and pro emphasis of many of the comments:

HR Lincoln (Tenn April 28, 2017 )

Stephens has it backwards. Climate science (and those who accept it) gives a range of probable outcomes. A doubling of CO2 is believed to lead to between 1.5 and 4.5 degrees Celsius. There is some possibility that the true result could be outside this range.

So called “skeptics”, on the other hand, claim that a doubling will result in between 0.5 and 1.5 degrees Celsius. They argue that there is no chance of it being any higher. Moreover, they ignore the scientific evidence–both empirical and from simulations–that indicates higher future warming.

So who is claiming to have 100% certainty?

RFLatta (Iowa City April 28, 2017 ):

This is the same old claim to “reasonable” incertitude that think tanks funded by the oil industry have circulated for many years. They take the correct assertion that evidence of athropogenic climate change is a matter of probabilities to it’s logically absurd conclusion: that we should discount any possibility of it’s likelihood no matter how much evidence there is. The irony is that those who stand to gain the most from selling oil still in the ground claim to have even more certainty about the science than scientists or environmentalists.

Corwin Kilvert (New York, NY April 28, 2017 ):

I think Bret Stephens makes an excellent point about the dangers of certainty. I’ve often felt that we live in a time of hyperbole, things are either never or always. People fail to approach subjects with a rational level of certainty. Look at how quickly the population responds to the latest meme or video of the moment. How can anyone with absolute certainty come to a conclusion of a video clip interaction, but so often we do. With real consequences. A little more critical thinking is certainly needed.

On the other hand if you truly want people to look a little bit harder at the climate change argument, then present us with the argument. Present the data. Show the probabilities. Discuss the models. Don’t be afraid of the details.

By the time that I am writing this blog (May 12th), Mr. Stephens has already written three more Op-Ed contributions to the NYT with which I have no arguments. President Trump is the focus in all three blogs; he seems to be a “safe” subject in The New York Times. Still, the climate change beginning in the NYT did leave an impact.

Stephens, formerly of the Wall Street Journal, faced intense backlash to the late-April opinion piece, in which he questioned any certainty in the political debate surrounding climate change. In it, he said, “if there were less certitude about our climate future, more Americans would be interested in having a reasoned conversation about it.”

Not only did other members of the scientific community and the press criticize his skeptical take, but there were also declarations on Twitter by people saying they were going to unsubscribe from the Times in reaction to the piece.

The Times ran a correction, which fixed a wrong statistic on climate data.

Stephens specifically stated in the piece that he doesn’t refuse the idea of climate change, and during an interview Sunday with CNN’s Fareed Zakaria, he once again asserted he doesn’t deny climate change or “that we need to address it.”

“Seriously,” he added for emphasis.

“The point of the article was to say that there is a risk in any predictive science of hubris,” Stephens said, referring, as an example, to the 2007 U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s report claiming a very high likelihood that Himalayan glaciers would melt by 2035 — which was later discredited.

The column, Stephen contended, was “an attempt to be was a warning against intellectual hubris.” What it wasn’t was an effort to “deny facts about climate that have been agreed by the scientific community,” he added.

“I think that’s a distinction that I’m afraid was lost in some of more intemperate criticism,” Stephens said. “But people who read the column carefully can see I said nothing outrageous or beyond the pale of normal discussion.”

The only climate-change-related reference that Mr. Stephens made in his first article was that of Andrew Revkin, an ex-environmental writer at The New York Times. Mr. Revkin has solid credentials for his writing on climate change and the way that Stephens used the quote, without including the context, leaves his credibility wanting.

Mr. Revkin is one of the 27 co-authors who wrote the recent paper, “Making the case for a formal Anthropocene Epoch: an analysis of ongoing critiques,” which was published in Newsletters on Stratigraphy Vol 50/2 (2017), 205-226. Here is the paper’s abstract:

Abstract : A range of published arguments against formalizing the Anthropocene as a geological time unit have variously suggested that it is a misleading term of non-stratigraphic origin and usage, is based on insignificant temporal and material stratigraphic content unlike that used to define older geological time units, is focused on observation of human history or speculation about the future rather than geologically significant events, and is driven more by politics than science. In response, we contend that the Anthropocene is a functional term that has firm geological grounding in a well-characterized stratigraphic record. This record, although often lithologically thin, is laterally extensive, rich in detail and already reflects substantial elapsed (and in part irreversible) change to the Earth System that is comparable to or greater in magnitude than that of previous epoch-scale transitions. The Anthropocene differs from previously defined epochs in reflecting contemporary geological change, which in turn also leads to the term’s use over a wide range of social and political discourse. Nevertheless, that use remains entirely distinct from its demonstrable stratigraphic underpinning. Here we respond to the arguments opposing the geological validity and utility of the Anthropocene, and submit that a strong case may be made for the Anthropocene to be treated as a formal chronostratigraphic unit and added to the Geological Time Scale.

The issue of this Op-Ed is not going away, no matter how many anti-Trump Op-Eds Mr. Stephens might write. It’s been reported that as a result of his contribution some readers are cancelling their subscriptions to The New York Times, making the publishers a bit nervous. Here is what Politico wrote about it:

New York Times publisher Arthur O. Sulzberger Jr. is making a personal appeal to subscribers who canceled because the paper hired Bret Stephens, a conservative columnist who has questioned some of the science behind the theory of climate change and the dangers it poses. In an email sent Friday afternoon and obtained by POLITICO, Sulzberger addresses subscribers who specifically mentioned the hiring of Stephens as a reason that they ended their subscriptions.

“Our customer care team shared with me that your reason for unsubscribing from The New York Times included our decision to hire Bret Stephens as an Opinion columnist. I wanted to provide a bit more context,” the email begins. Stephens, who left The Wall Street Journal to join the Times, is also well known as a Pulitzer Prize-winning conservative writer who has written strongly against President Donald Trump, often engaging in public battles during the campaign with the likes of Fox News anchor Sean Hannity. His first column for the Times last month argued that climate data create the misleading impression that we know what global warming’s impact will be, leading to reader complaints, some canceled subscriptions and a public editor column. In the letter to former subscribers, Sulzberger says it’s important to underscore that the newsroom functions separately from the opinion department, and that New York Times executive editor Dean Baquet “has sharply expanded the team of reporters and editors who cover climate change.” “No subject is more vital,” Sulzberger said.

Sulzberger then lists several articles about climate change, including a photo essay about rising waters threatening China’s cities; environmental rules, regulations and other policies rolled back during Trump’s first 100 days in office; and a recent issue of the Sunday magazine dedicated to the climate’s future.

Stay tuned!