Tomorrow is the 50th Earth Day, my wife’s birthday, and the 8th birthday of this blog. Happy Birthday to everybody.

This year, however, Earth Day will not be the same festive occasion that will include community events out in the streets, although there will be some online events. Most of us are in lockdown, prisoners in our own homes if we are lucky enough to have them. Worldwide, the only news that we get is pandemic-related.

Meanwhile, the advance of climate change continues. Both of these malignant forces are global but they have very different rates of progress. The COVID-19 pandemic started with a doubling time of a few days in China and quickly expanded globally from there. As I have mentioned before, we still don’t know yet (or have the resources to determine) how to exactly to measure its expansion. The current procedure of focusing only on symptomatic cases is not very helpful given recent news of how many of the infected are asymptomatic. Aside from China, we have concentrated almost exclusively on the US and other (primarily European) rich countries. Next week I will look into coronavirus’ impact on the vast majority of humanity in the developing world.

We measure the progress of climate change, on the other hand, in generations. Many of us use the end of the century as the endpoint or target of our studies.

Earth Day is an appropriate occasion to try to connect the two disasters. Pope Francis did this as we approached Good Friday:

Pope Francis has said the coronavirus pandemic is one of “nature’s responses” to humans ignoring the current ecological crisis.

In an email interview published Wednesday in The Tablet and Commonwealth magazines, the pontiff said the outbreak offered an opportunity to slow down the rate of production and consumption and to learn to understand and contemplate the natural world.

“We did not respond to the partial catastrophes. Who now speaks of the fires in Australia, or remembers that 18 months ago a boat could cross the North Pole because the glaciers had all melted? Who speaks now of the floods?” the Pope said.

“I don’t know if these are the revenge of nature, but they are certainly nature’s responses,” he added.

Meanwhile, rather than move to mitigate the ravages of climate change, President Trump rolled back the EPA’s emission standards:

The White House on Tuesday confirmed it would reject the federal fuel economy standards set under the Obama administration, lowering the minimum mileage of the average 2025 vehicle from 46.7 miles per gallon to 40.4 miles per gallon.

The move was billed by the administration as a way to reduce the cost of owning a vehicle while also saving lives, according to Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Andrew Wheeler, who said on Tuesday the new standards “will get more Americans into newer, cleaner, safer vehicles.”

President Trump may be contributing to higher emissions but that is not the trend everywhere.

Big things have been happening during the last two months:

For starters, coronavirus shutdowns have brought about a (temporary) decline in carbon emissions. China has seen decline of 18% (250 million metric tons) from early February to mid-March. In Europe, 2020 has shown an estimated decline of 400 million metric tons. We don’t have exact numbers for the US yet but a sharp decline is anticipated. From India’s capital, New Delhi, you can start to see the snowy Himalayan Mountains, a rare feat that hasn’t been possible for many years.

Most people and business are frozen at home, resulting in steeply plunging GDPs, usually the main drivers of carbon emissions.

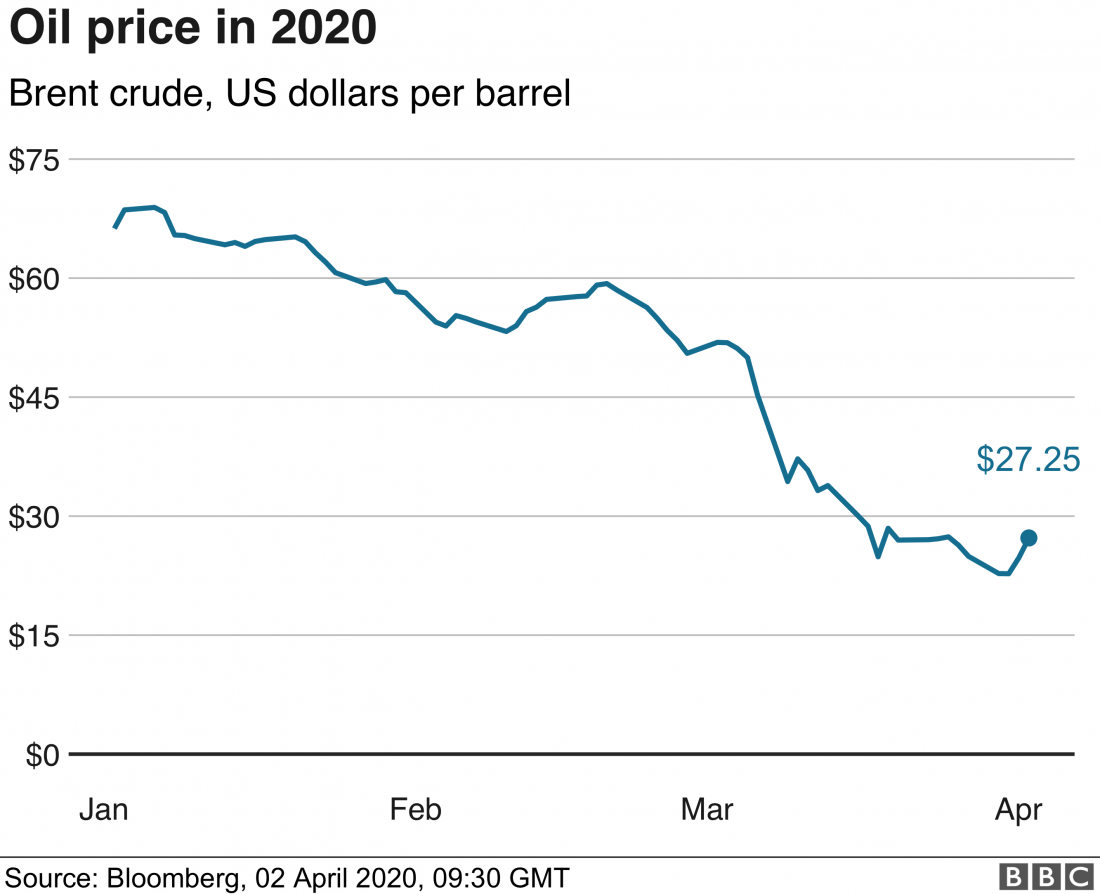

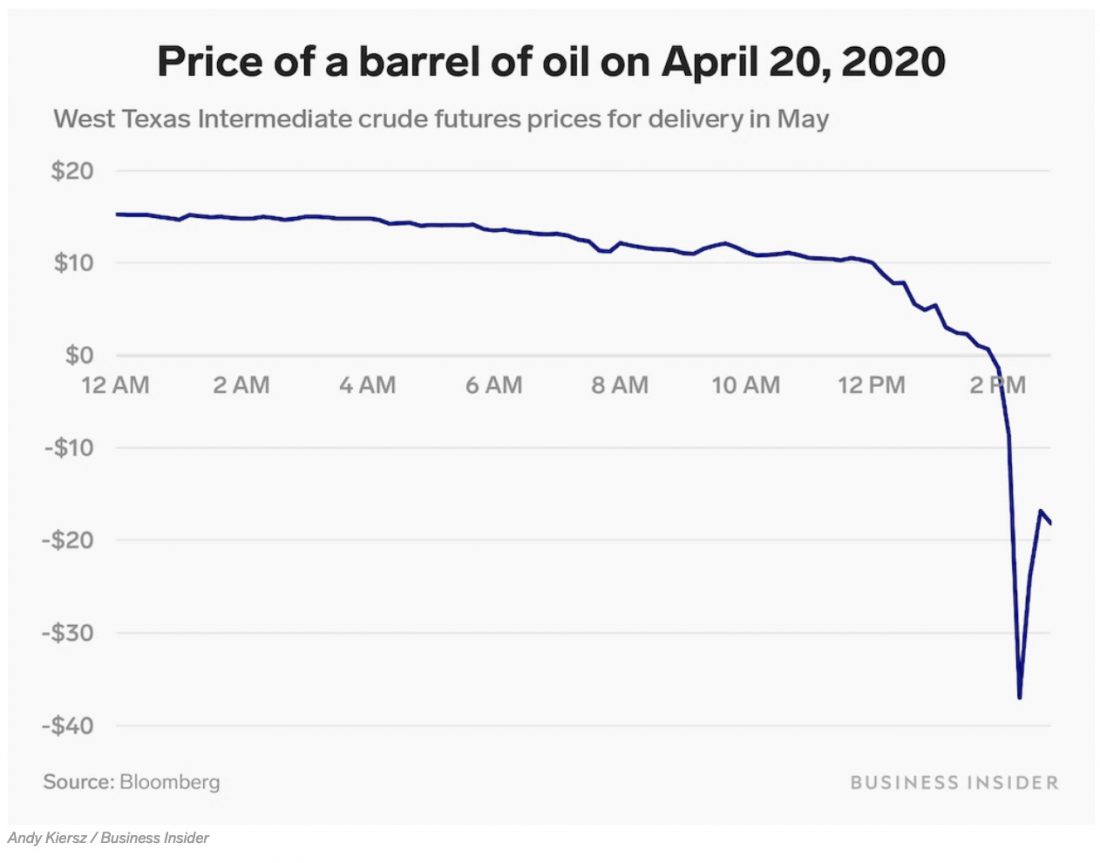

This has also resulted in an almost total collapse of the price of oil and a saturation of storage capacity of unused oil.

While these graphs show Brent crude oil and WTI, respectively, both numbers are historic.

While these graphs show Brent crude oil and WTI, respectively, both numbers are historic.

The flip side of the decline in oil is a potential boon for renewable energy:

Oil Companies Are Collapsing, but Wind and Solar Energy Keep Growing

A few years ago, the kind of double-digit drop in oil and gas prices the world is experiencing now because of the coronavirus pandemic might have increased the use of fossil fuels and hurt renewable energy sources like wind and solar farms.

That is not happening.

In fact, renewable energy sources are set to account for nearly 21 percent of the electricity the United States uses for the first time this year, up from about 18 percent last year and 10 percent in 2010, according to one forecast published last week. And while work on some solar and wind projects has been delayed by the outbreak, industry executives and analysts expect the renewable business to continue growing in 2020 and next year even as oil, gas and coal companies struggle financially or seek bankruptcy protection.

In many parts of the world, including California and Texas, wind turbines and solar panels now produce electricity more cheaply than natural gas and coal. That has made them attractive to electric utilities and investors alike. It also helps that while oil prices have been more than halved since the pandemic forced most state governments to order people to stay home, natural gas and coal prices have not dropped nearly as much.

Even the decline in electricity use in recent weeks as businesses halted operations could help renewables, according to analysts at Raymond James & Associates. That’s because utilities, as revenue suffers, will try to get more electricity from wind and solar farms, which cost little to operate, and less from power plants fueled by fossil fuels.

Many of these changes are temporary and will revert to normal once the pandemic runs its course. When and how is still largely unknown.

In the meantime, the United States’ Southwest is experiencing a severe, climate change-driven drought (coined a megadrought) that might last a generation.

Dr. Williams and his colleagues reconstructed drought conditions in the Southwest for every year back to 800 A.D., using tree growth as a proxy for soil moisture content. Examining nearly 1,600 tree-ring records, they found four periods of more than two decades each during which soil moisture content was far below the baseline for the entire 1,200 years, indicating severe drought conditions of lack of precipitation and increased dryness. One of these megadroughts, in the 13th century, lasted more than 90 years.

Their analysis showed that, as measured by soil moisture content, the current drought is more severe than three of the ancient ones. Only one in the late 1500s was worse, and not by much, the researchers said.

We’ll have to wait and see what all of these things mean for our futures.

Stay tuned and keep safe.

This year’s earth day might have been the best earth day in a very long time because of the pandemic. Since people have to stay home, the need for gas has decreased and so has pollution from factories.