When we vote in an election, we balance between what we perceive to be good for us personally and what we perceive to be good for society at large. If we are well-off with a good job, we may prioritize money and vote for the candidate that we believe will reduce our taxes. If we are a member of a minority that has experienced discrimination, we may vote for the candidate that we believe will work toward social justice, equity, and reform. In general, we look for candidates who will embody our priorities and shape our government to reflect our views on a better city/state/country.

I addressed some of these issues around the time that the newly-elected President Trump took us out of the Paris Accord in 2017. President Trump justified the withdrawal with his “America First” argument.

Thursday (June 1st) was an event to remember. President Trump did indeed turn his back on the world, declaring that he was elected to serve Pittsburg and not Paris – except for the small detail that Pittsburg didn’t vote for him. Allegany County gave 259,480 votes to Trump and 367, 617 votes to Clinton.

Aside from that small discrepancy from reality, the speech was an astronomical declaration that the US is an isolated planet unaffected by anything that happens around it. Strangely, there was not a word in the speech about the future. Last week’s blog focused on the conflict between globalism and nationalism. I wrote there that “me” and “them” are very well defined. “We” includes me but needs an additional description of the collective that is being referring to. I am especially interested in where we position our family members and friends on this spectrum. In my book (Climate Change: The Fork at the End of Now), I defined “Now” in terms of the expected life span of my grandchildren, which approximately brings me to the end of the century.

On Tuesday, November 3, 2020, the American people voted President Trump out and elected VP Biden as our next president. Nevertheless, the following day, our withdrawal from the Paris accord became final.

I was reminded of the us vs. them issue when I read an Op-Ed in The New York Times that tried to explain why—in spite of his many policies blocking immigration—Latino voters didn’t overwhelmingly vote against President Trump:

“Some Latinos Voted for Trump. Get Over It: I’m Latina. I still don’t know what that means.

By Isvett Verde”Many people were surprised, but they shouldn’t be. In 1984, 37 percent of Latinos voted for Ronald Reagan; 40 percent voted for George W. Bush in 2004. It would be easy to dismiss these voters as self hating, or racists. But that’s a simplistic way of viewing this wildly diverse and complex demographic.

The reason the “Latino vote” befuddles is because it doesn’t exist, nor do “Latino issues.” If we want to understand how Latinos vote, we should start by retiring the word “Latino” entirely — and maybe “Hispanic,” too, a term first used by the United States government in the 1970 census that is based solely on the language native to the European settlers who conquered the Americas. These labels have served only to reduce us to a two-dimensional caricature: poor brown immigrants who always vote Democrat.

Latinos, like all Americans, are motivated by the issues that affect them directly. Those can vary depending on factors like our religion, where we grew up, whether we are first generation or our ancestors lived in North America long before the United States existed. Many Democrats act as if Latinos care only about immigration policy. In fact, a recent survey by UnidosUS, an advocacy group, and Latino Decisions, a polling and research firm, found that Latinos are more concerned about jobs and the economy.

Her main argument was that Latinos are not a monolith. They don’t all vote in one bloc or have the same priorities. In other words, as with non-Latinos, “us” can mean a lot of different things.

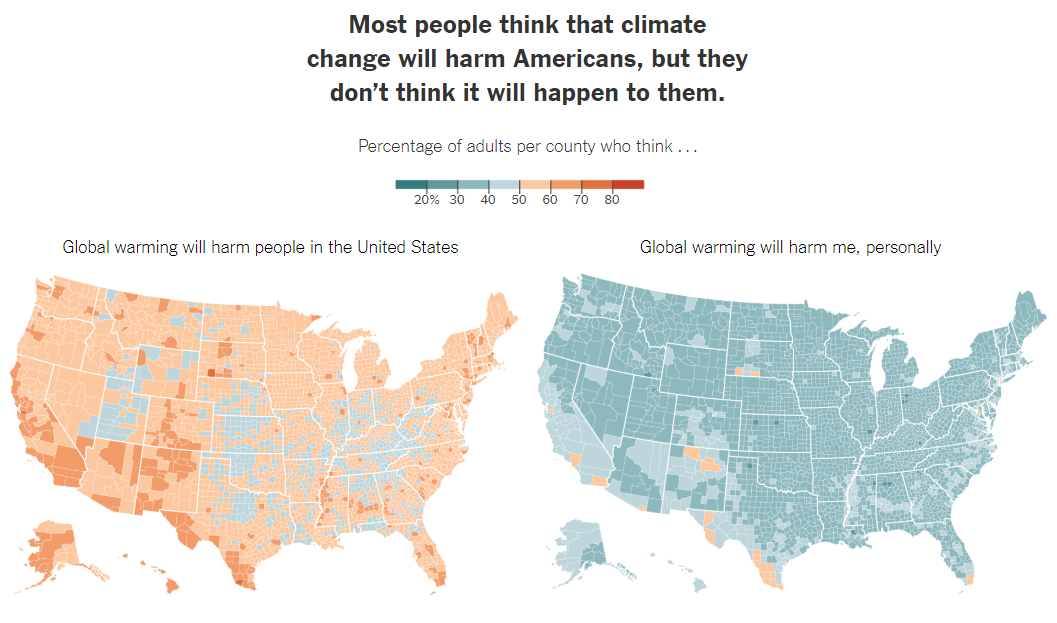

Last year, in its “Learning Network” section, The New York Times, reprinted 24 figures from earlier articles in order to illustrate some of the many aspects of climate change. I find the following figure especially relevant here as it demonstrates another separation of “me vs. them.” It compares the distribution of people who think that climate change will directly harm Americans with those who think it will affect them personally:

This figure is based on an older article that cites a 2016 Yale survey. Here is the data on risk perception:

| Worried about global warming | Worried – 58% | Not worried – 42% |

| Global warming is already harming people in the US | Now/within 10 years – 51% | 25 years/never – 49% |

| Global warming will harm me personally | Great/moderate amount – 40% | 50% |

| Global warming will harm people in the US | Great/moderate amount – 58% | 33% |

| Global warming will harm people in developing countries | Great/moderate amount – 63% | 25% |

| Global warming will harm future generations | Great/moderate amount – 70% | |

| Global warming will harm plants and animals | Great/moderate amount – 69% |

Almost 60% of Americans think that climate change will harm people within the US (them) but that number drops significantly when participants are asked if they would personally be affected (me).

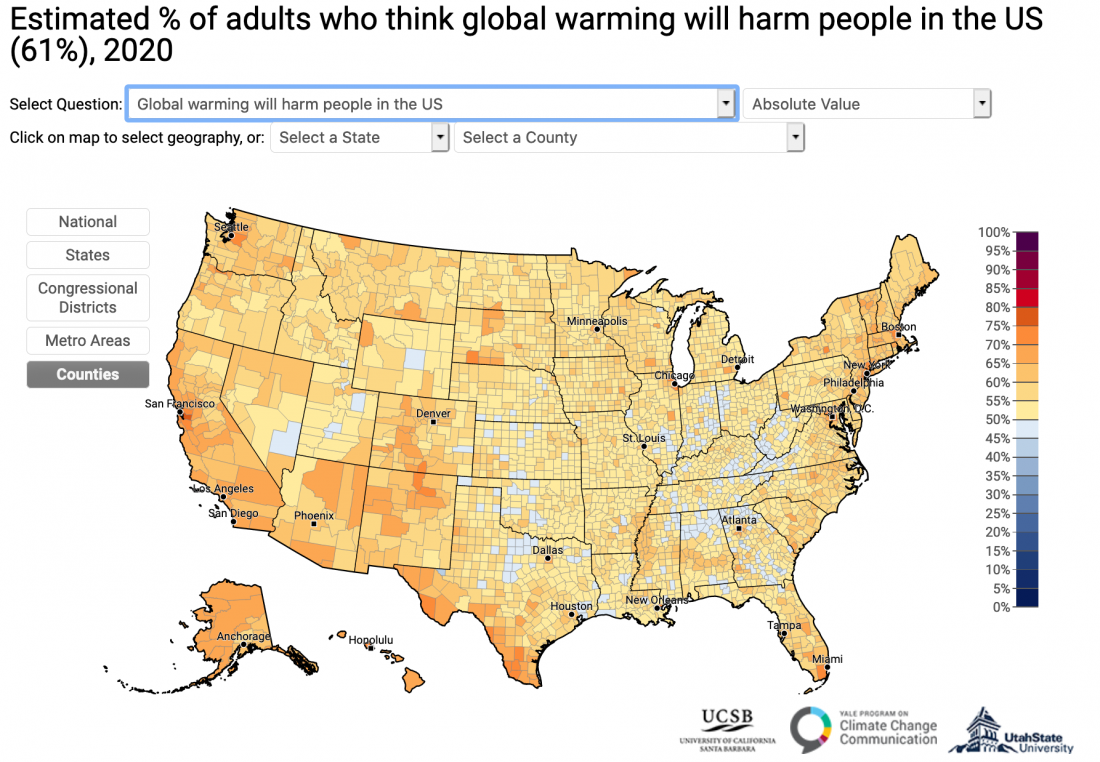

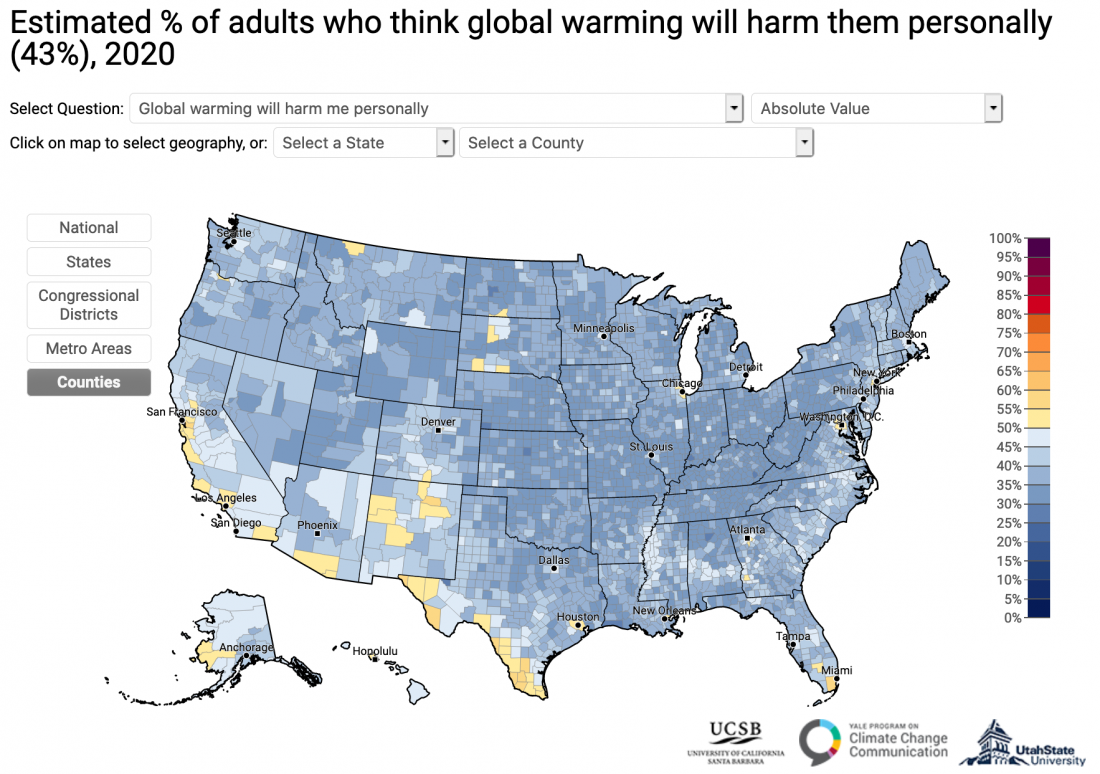

The figure and chart above reflect the data gathered between 2008 and 2016 by the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication and the George Mason Center for Climate Change Communication. Of course, this data is 4 years old and constantly in flux but the new (2020) version hasn’t changed much:

What can we do about the imbalance between the “me,” “they,” and “us”? This is an issue that I have grappled with for most of my academic career. I am giving my students an end-of-semester assignment to compile similar data that reflects their own perspectives on the balance between “me vs. them.”

Next week I will finish my set of “Teaching Moments” blogs by going back to the drafting of the American Constitution. I’ll look at how the Founding Fathers attempted to balance power between the territories (e.g. states) and individuals in selecting the US government.

It’s kind of surprising not more people in flood zones (areas of Florida, for example) believe climate change will impact them.