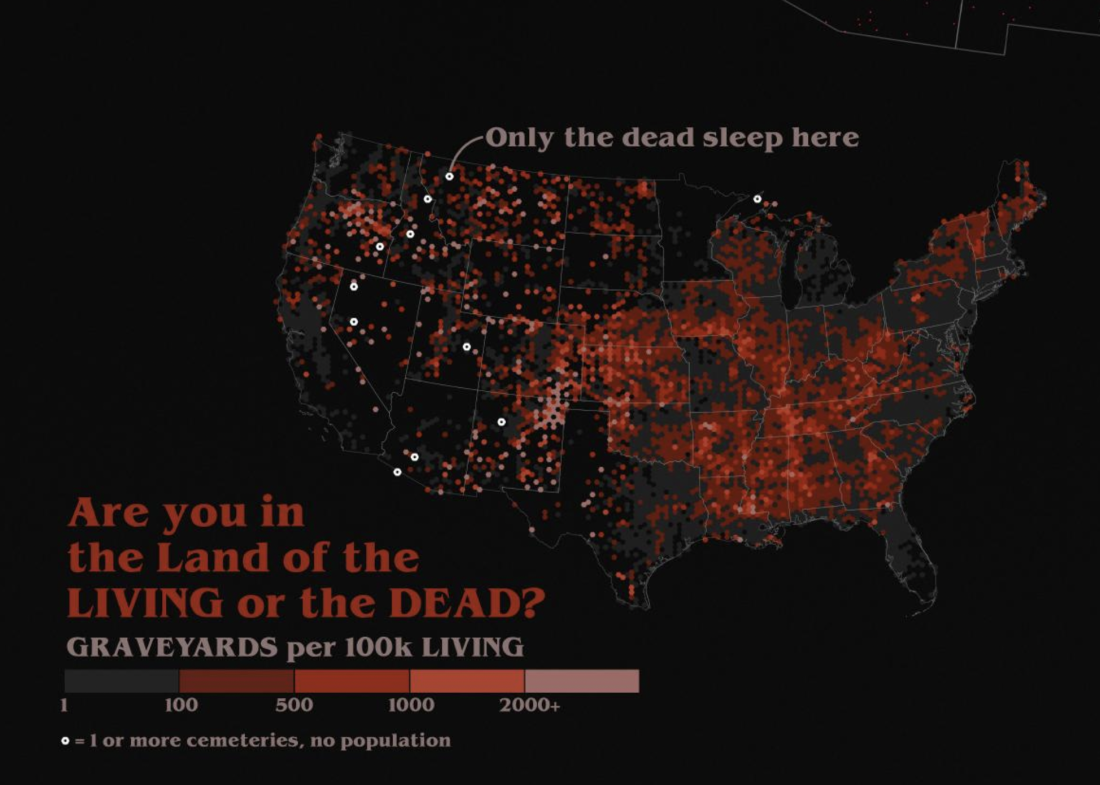

Figure 1 – Graveyards of the contiguous US (Source: Joshua Stephens via Insider)

Figure 1 – Graveyards of the contiguous US (Source: Joshua Stephens via Insider)

I will die in the Anthropocene. The only uncertain part of this statement is whether the global epoch that is now under consideration will be officially named as such by that time. I will not be alone. At the end of last year, the global population passed 8 billion. All 8 billion will die within this epoch. More than that, I was born in 1939. A quick estimate of all the people who have lived on Earth since I was born (the estimated global population for 1939 is about 2 billion) can be helped by an estimate of the number of people that were born over this period (280 million). The total number of people born after the start of the Anthropocene will exceed 50 billion (we obviously have no idea how long the Anthropocene will last and in what form will it end. Most of the dead are buried one way or another (cremation vs. burying will be discussed in the next blog). As I’ve mentioned before, our planet is finite. The situation in the United States is shown in the opening picture of the blog with the suggestion that we are now living in the “land of the dead.” The global population is still increasing (though at a slower rate now). What can we do about it??

This blog will focus on two issues directly connected to our mortality: the finite availability of burial land and the unfulfilled wish of many of us for our stories to remain available after we are gone in a way that will not crowd the planet with stone memorials.

There is some background to these wishes:

In a previous blog (April 12, 2022), I described a recently-erected monument in Farsleben, Germany, which marks the liberation of my group of Bergen-Belsen inmates by the American army. The liberation took place on April 13th as the German army tried to move us from our camp to another camp farther away from the front line (Bergen-Belsen was liberated by the British army on April 15th).

I was involved in the construction of the monument. During the construction process, a friend (and relative), who works in the electronics industry suggested that we embed an electronic chip in the monument that could connect visitors with the story of our liberation. He donated a few chips that are about to be embedded.

A short internet search quickly convinced us that the appropriate technology exists; it has been dubbed the “Personal RosettaStone.” An article from 2010 describes it:

March 12, 2010 — After he dies, Christopher Hill plans to speak to his grandchildren, great grandchildren and even future generations from beyond the grave – not through a psychic medium or his last will and testament, but through a microchip.

“I think that when you walk by a gravestone and only see things like a few words, or a name and a date, it can be somewhat cold, impersonal, and almost incomplete,” the 41-year-old from Northern Virginia told ABCNews.com. “This gravestone is supposed to tell the story of a person, and provide you that connection or emotional remembrance.”

With new technology developed by a Phoenix, Ariz. company, he now thinks that could be a real possibility.

Launched by Objecs, LLC last month, Personal RosettaStones are iPod-sized stone tablets embedded with RFID (Radio Frequency Identification) tags that can store up to 1,000 words and a picture. When they’re near a mobile phone equipped with compatible technology, the information in the microchip is beamed right on to the cell phone screen. Objecs says the tags, which can be affixed to headstones, can last for up to 3,200 years.

A more recent link lets us see more, although the company’s websites don’t seem to be in service any longer.

As the example shows, the technology is based on RFID (Radio-frequency Identification) tags and is part of the more general category of the Internet of Things.

Such a solution can enhance the durability of our stories, but it will not contribute to more effective burial practices. It can, however, serve as an intermediate step in the burial transition.

I have played with the concept of perpetuating memories for some years now. The first time that I tried was shortly after the German reunification (around 1990). Closely after that event, the German government announced its intent to build a Holocaust Memorial in Berlin. I was inspired by the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, DC and tried to figure out what it would take to construct the memorial as a winding labyrinth with similar characteristics. The length of the Vietnam memorial is 200 feet, with more than 58,000 names engraved. My question was what area it would take to construct a similar memorial with 6 million names engraved using similar fonts and sizes to those at the Vietnam memorial. I have since lost the details of these calculations, but I remember my conclusion – such a labyrinth was practical within Berlin’s city limits.

Figures 2 & 3– Berlin memorial for the Jews murdered in Europe (Berlin Holocaust Memorial)

The actual memorial was dedicated in 2005, and it contains 2711 slabs, shown in Figures 2 & 3 from two perspectives. Rather than being carved into the slabs themselves, an attached underground “Place of Information” holds the names of approximately 3 million Jewish Holocaust victims, obtained from the Israeli museum Yad Vashem.

What Christopher Hill (see the beginning of this blog) wanted to leave to his grandchildren is now being happening without any electronic chip (or headstone). People like Steven Spielberg are “immortalizing” individual experiences of recent genocides, with an emphasis on Holocaust survivors:

In 1994, after the filming of Schindler’s List, Steven Spielberg founded the Survivors of the Shoah Visual History Foundation with the aim of videotaping 50,000 first-person accounts by Holocaust survivors and witnesses.

The massive global documentation effort began with the first interview on April 18, 1994. The foundation trained 2,300 interviewer candidates in 24 countries, hired 1,000 videographers, and recruited more than 100 regional coordinators and staff in 34 countries to organize the interviewing process in their respective regions. Between 1994 and 2000, interviews with Holocaust survivors and witnesses took place in 56 countries and were conducted in 32 languages.

Within the context of commemorating the Holocaust victims and survivors, a large step forward was recently taken by both Yad-Vashem, the Holocaust memorial in Jerusalem, and the “World Memory Project” of the US Holocaust Memorial Museum at the World Memory Project. The Yad-Vashem “Book of Names” installation is on loan to the UN General Assembly for a month, starting with January 27, International Holocaust Memorial Day. (Holocaust ‘Book of Names’ to be inaugurated at the UN underscores the individual identities of the 6 million – Jewish Telegraphic Agency) After New York, it will return to Jerusalem at the end of February. I will visit the UN headquarters to see the installation in a week. Most of the “World Memory Project” is online. I tested it on my iPhone. Within a few minutes, I was able to find myself and most of my family after supplying only my last name. The site contains first names, date of birth, in many cases date of liberation, and the original source of information.

Traditional headstones include a person’s name, date of birth, and date of death, often with a sentence about the greatness of the deceased. We now have the technology to replace headstones and cemeteries with electronic memorials that take up much less space and include much more information.

I realize that this blog is loaded with the death culture of the rich, western world. In next week’s blog, I will try to expand the concept beyond the rich world with an emphasis on India and China, including a distinction between burials and cremation.