Happy New Year!

My last blog ended with a quote from Karan Singh, a former minister of population in India, who said, “Development is the best contraceptive.” This was supported by data which shows that fertility rates and population growth tend to decrease as the GDP/person and the overall educational levels increase. Of course, poverty is not restricted to developing countries; rich countries have their own populations of poor people. However, statistics such as fertility rates and population growth reflect the decisions of individuals, and therefore do not always reflect the projected country averages. We measure individual poverty levels in all countries by looking at income distribution and the degree of inequality associated with such distributions.

I am starting to write this post on Friday, January 3. It’s bitter cold outside and we have just come through the major snow storm that hit a significant part of the country. I live and work in NYC and my school, like most others in the City, is closed because of the weather.

In November, we elected Bill de Blasio to be our 109th mayor, and he was sworn in on Wednesday (January 1, 2014) to start his term. His winning election campaign promised to “take dead aim at the Tale of Two Cities,” and “leave no New Yorker behind.” During de Blasio’s inauguration, the Rev. Frederick Lucas was quoted as saying, “Let the plantation called New York City be the city of God, a city set upon the hill, a light shining in darkness.” When our new mayor speaks of “two cities,” he is referring to the widening gap between the rich and poor within New York. His call for action struck a chord with voters that translated to a majority of roughly 75% against his Republican opponent in the November election.

When my French cousin heard about these results, I got a sarcastic congratulatory email on having finally elected a “commie” to lead us. I very patiently explained to him that de Blasio is not a “commie,” but that the widening gap between rich and poor is a real issue that needs to be addressed. On the off chance he was not convinced, I suggested that his mother, a longtime member of the left in French politics, might be tempted now to move to NYC. I got an immediate response from her, informing me that she doesn’t want to give up her job in a French company and she is happy where she is. Oh well, it was worth a try 🙂 .

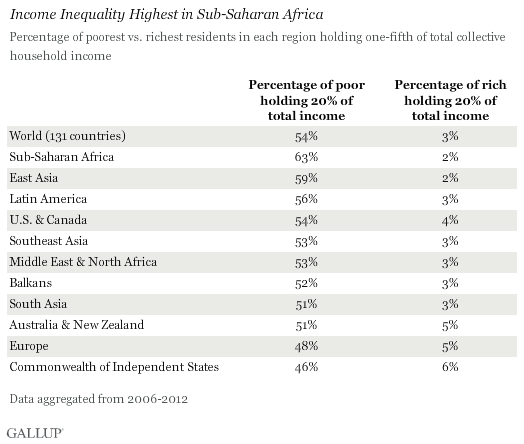

The expanding gap between rich and poor is not only NYC issue; it is a global issue. A recent Gallup report quantifies the issue in the table below:

When I discuss this in class in the context of climate change (see the November 26 and December 3, 2012 blogs), the most common reaction from students is: “So what? What does this have to do with climate change anyway?”

When I discuss this in class in the context of climate change (see the November 26 and December 3, 2012 blogs), the most common reaction from students is: “So what? What does this have to do with climate change anyway?”

Here is one appropriate response, as given in Bjorn Lomborg’s recent op-ed in the New York Times with the following emphasis:

PRAGUE — THERE’S a lot of hand-wringing about our warming planet, but billions of people face a more immediate problem: They are desperately poor, and many cook and heat their homes using open fires or leaky stoves that burn dirty fuels like wood, dung, crop waste and coal.

About 3.5 million of them die prematurely each year as a result of breathing the polluted air inside their homes — about 200,000 more than the number who die prematurely each year from breathing polluted air outside, according to a study by the World Health Organization. There’s no question that burning fossil fuels is leading to a warmer climate and that addressing this problem is important. But doing so is a question of timing and priority.

There are many problems that repeatedly stand in the way of such necessary change. Among these are the ongoing conflicts between developed and developing countries that impede any global agreement to confront climate change, an issue that once again came to light at the recent POP 19 meeting in Warsaw, Poland.

Paul Krugman examines a different aspect of inequality in his recent op-ed column in the New York Times, in which he argues that inequality is a serious impediment for economic growth:

The best argument for putting inequality on the back burner is the depressed state of the economy. Isn’t it more important to restore economic growth than to worry about how the gains from growth are distributed?

Well, no. First of all, even if you look only at the direct impact of rising inequality on middle-class Americans, it is indeed a very big deal. Beyond that, inequality probably played an important role in creating our economic mess, and has played a crucial role in our failure to clean it up. Start with the numbers. On average, Americans remain a lot poorer today than they were before the economic crisis. For the bottom 90 percent of families, this impoverishment reflects both a shrinking economic pie and a declining share of that pie. Which mattered more? The answer, amazingly, is that they’re more or less comparable — that is, inequality is rising so fast that over the past six years it has been as big a drag on ordinary American incomes as poor economic performance, even though those years include the worst economic slump since the 1930s.

The reduction of poverty on any scale can bring about many positive changes in infrastructure, such as better health care, education and a pension system. As a result, such a change in economic situation is probably the best way to reduce fertility; unfortunately, this cannot entirely ensure the stability of future populations at replacement rate. A fertility rate below the replacement rate presents its own challenges that I will try to explore in the coming blogs.