(Source: Reuters)

The COP30 final text, officially referred to as the Belém Package or the Global Mutirão Decision, is a consensus document that aims to accelerate climate action among all signatory nations of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). The United States did not have a vote since the Trump administration did not send an official delegation. This blog consists of three central elements of the Belem Package: key paragraphs from the final text, a sample of the global reaction to the package, and a post-conference NYT summary of the Trump administration’s recent actions to nullify prior decisions aimed at mitigating climate change. The issue in the package that was at the center of global attention was its silence about the future use of fossil fuels.

The essence of the Belém Package:

One hundred and ninety-five Parties adopted the Belém Package this afternoon, demonstrating humanity’s resolve to turn urgency into unity, and unity into action in tackling climate change. The 29 decisions approved by consensus include agreements on topics such as just transition, adaptation finance, trade, gender, and technology, renewing the collective commitment to accelerated action, and a climate regime more connected to people’s lives.

“As we leave Belém, this moment must not be remembered as the end of a conference, but as the beginning of a decade of turning the game”, said COP30 President, André Corrêa do Lago. “The spirit we built here does not end with the gavel; it continues in every government meeting, every boardroom and trade union, every classroom, laboratory, forest community, large city, and coastal town.”

The approved decisions in the Belém Package include a commitment to triple adaptation finance by 2035, emphasizing the need for developed countries to significantly boost climate finance for developing nations. Parties concluded the Baku Adaptation Roadmap, which approves and establishes the work for 2026-2028, until the next Global Stocktake of the Paris Agreement.

The climate conference is also finalizing a comprehensive set of 59 voluntary, non-p non-prescriptive indicators to track progress under the Global Goal on Adaptation.These indicators span all sectors, including water, food, health, ecosystems, infrastructure, and livelihoods, and integrate cross-cutting issues such as finance, technology, and capacity-building.

Parties approved a just transition mechanism that puts people and equity at the center of the fight against climate change. The initiative aims to enhance international cooperation, technical assistance, capacity-building, and knowledge-sharing, and enable equitable, inclusive just transitions.

Among other texts, countries adopted a Gender Action Plan that enhances support for national gender and climate change focal point. The initiative advances gender-responsive budgeting and finance, and promotes the leadership of Indigenous, Afro-descendant, and rural women, among other topics.

Another adopted document, the Mutirão Decision, reaffirms our determination to enhance our collective ambition over time to move from negotiations to implementation now that the Paris Agreement and its cycles are fully in motion. The following implementation mechanisms will help to accelerate this process:

- The Global Implementation Accelerator: A collaborative and voluntary initiative launched under the leadership of the COP30 and COP31 Presidencies to support countries in implementing their NDCs and National Adaptation Plans (NAPs).

- The Belém Mission to 1.5: An action-oriented platform under the COP29-COP31 troika to foster enhanced ambition and international cooperation across mitigation, adaptation, and investment.

“The Mutirão Decision defines the spirit of our COP: a global mobilization against climate change that celebrates the 10th anniversary of the Paris Agreement and paves the way for more ambition during this critical decade”, says Corrêa do Lago.

Both the Global Implementation Accelerator and the Belém Mission to 1.5 will work complementarily with the vision presented by the Climate High-Level Champions for the next five years of the Action Agenda. The Action Agenda structures the work of more than 480 initiatives that bring together 190 countries and tens of thousands of businesses, investors, subnational governments, and civil society organizations to support the implementation of the GST.

Corrêa do Lago emphasized that the work is just beginning, as Brazil will serve as COP President until November 2026. He reaffirmed Brazil’s commitment to advancing climate action by focusing on three key pillars of COP30: strengthening multilateralism and the climate regime, connecting climate initiatives to people’s daily lives, and accelerating the implementation of the Paris Agreement.

Below is a sample of the global attitude toward the package:

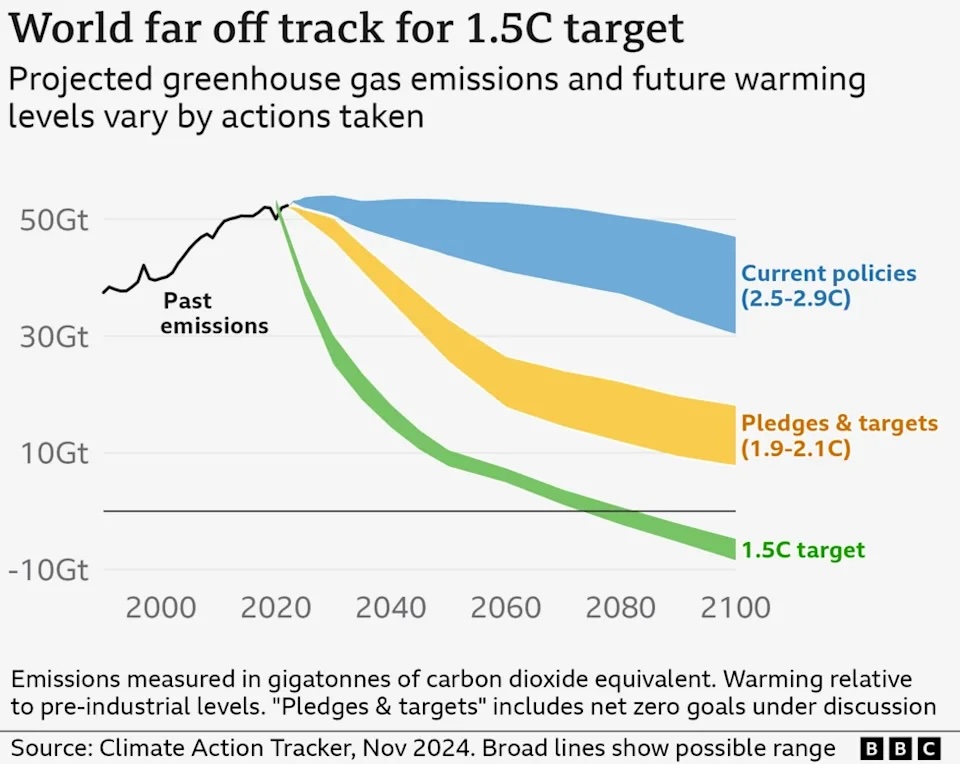

At one stage it looked like COP30 might crack the hardest nut in climate policy – reaching agreement on phasing out fossil fuels. Nations agreed two years ago that it was necessary to move away from fossil fuels. But no plan had yet been devised to get there.

Brazil had a plan: build support for a roadmap to phase out fossil fuels, championed by President Lula and pushed strongly by Environment Minister Marina Silva. It drew support from more than 80 countries, including major fossil fuel exporters such as Norway and Australia. Anticipating pushback, Brazil worked to boost support outside the main talks before bringing the plan in.

It didn’t work. By the end of COP30, all mention of a fossil fuel roadmap had been scrubbed from the text of the final outcomes, following fierce pushback from countries such as Russia, Saudi Arabia and India and many emerging economies.

Instead, countries agreed to launch “the Global Implementation Accelerator […] to keep 1.5°C within reach” and “taking into account” previous COP decisions. This initiative will be shepherded by the Brazilian COP30 Presidency and the leaders of next year’s COP31 talks, Turkey and Australia.

President Lula vowed to continue advocating for a fossil fuel roadmap at the G20. Colombia and the Netherlands will hold a conference on fossil fuel phaseout in April 2026. The COP30 decision text also makes reference to a “high-level event in 2026” which could take place in the Pacific. Without blockers of consensus at these meetings, a coalition of willing countries could make real progress in setting timelines and exchanging policy ideas for fossil fuel phase-out.

The New York Times summarized President’s Trump’s second term actions against climate change mitigation:

“The ‘Drill, baby, drill’ agenda has not materialized,” said Kenneth B. Medlock, an energy economist at Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy in Houston.

And yet the uncertain investment climate for fossil fuels comes as the industry’s political influence has soared this year.

A sweeping domestic policy bill that Mr. Trump signed into law this summer is already yielding nearly $6 billion in tax breaks this year for the country’s biggest oil and gas companies, a New York Times analysis of investor statements and public records shows.

At the same time, Mr. Trump is working to repeal dozens of environmental regulations that added costs for fossil fuel companies. He has opened up millions of acres of ecologically sensitive land in Alaska to drilling, including the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge’s coastal plain, and is poised to deliver millions of acres of offshore ocean waters for new drilling as well.

The Trump administration on Monday asked a federal court to strike down limits on soot released by power plants and industrial facilities and on Tuesday said it would delay by three years a requirement that coal-fired plants clean up toxic coal waste.

The president has struck deals requiring countries in Europe and Asia to purchase American liquefied natural gas for years to come. He has hobbled wind and solar projects and electric vehicles that were cutting into oil’s market share. And his administration has blocked other nations from imposing climate rules that could drive up costs for American oil and gas companies.

And last week, as nations gathered in Belém, Brazil, for a United Nations summit to tackle climate change, Mr. Trump hosted Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman of Saudi Arabia in the White House. Prince Mohammed’s oil-rich country has worked closely with the Trump administration to thwart international climate agreements — even as Saudi Arabia has an ambitious plan to diversify its own economy away from oil by 2030.

This blog is the last one to cover COP30. Since I was busy recently with efforts to connect the history of the Holocaust to present global threats, I will return to this issue another time.

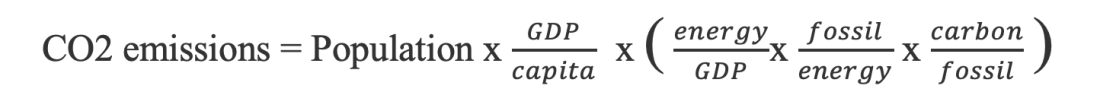

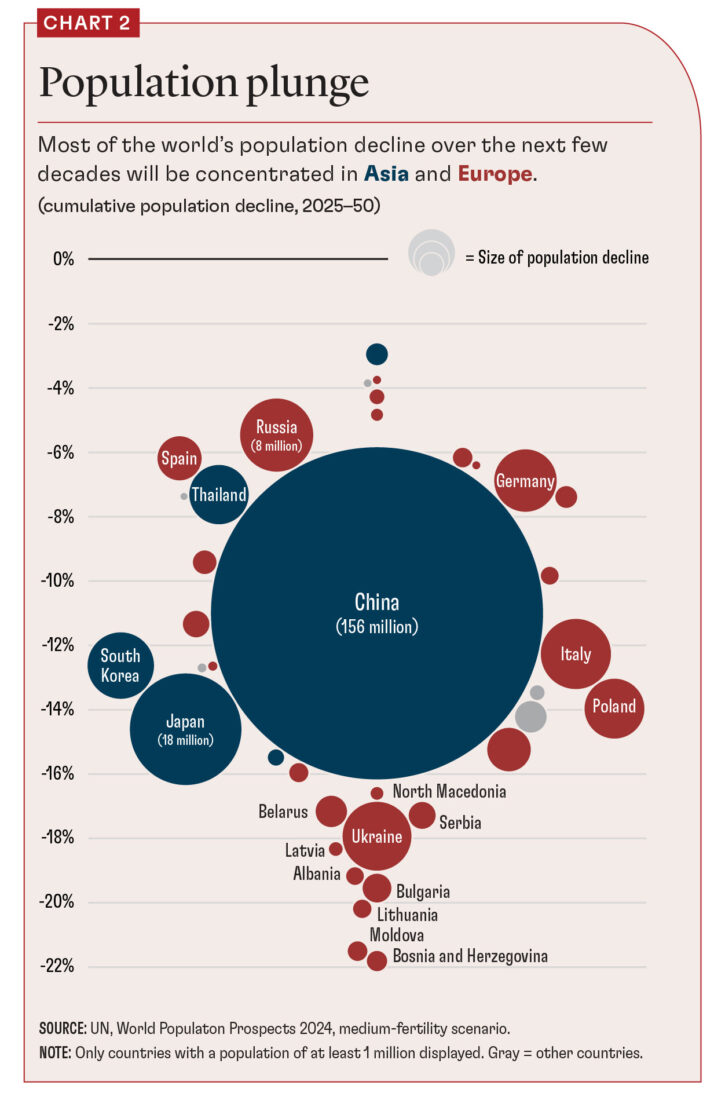

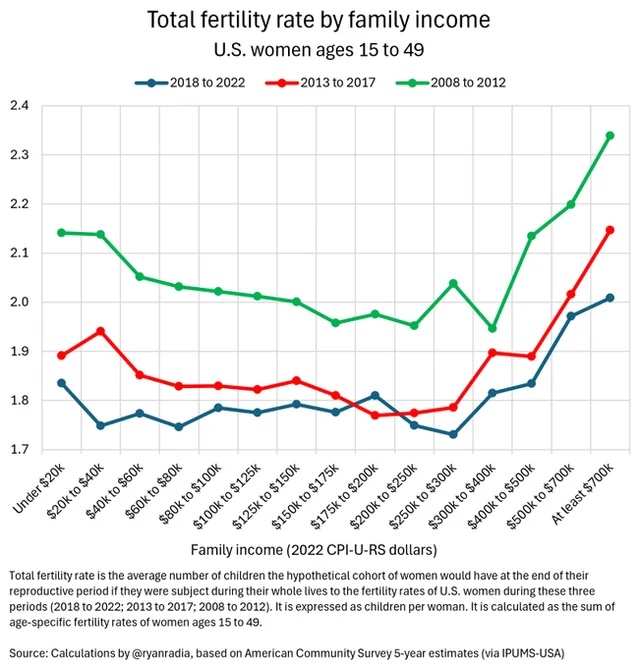

Following the IPAT calculation, I often hear the perspective that one should not be too concerned with declining population because it would also result in a decline in environmental damage. To me, this suggests a “back to the cave” attitude where the best policy is to return to an earlier time when the average

Following the IPAT calculation, I often hear the perspective that one should not be too concerned with declining population because it would also result in a decline in environmental damage. To me, this suggests a “back to the cave” attitude where the best policy is to return to an earlier time when the average

Figure 1 – Predicted population plunge, 2025-2050 (Source: UN, World Population Prospects 2024, via

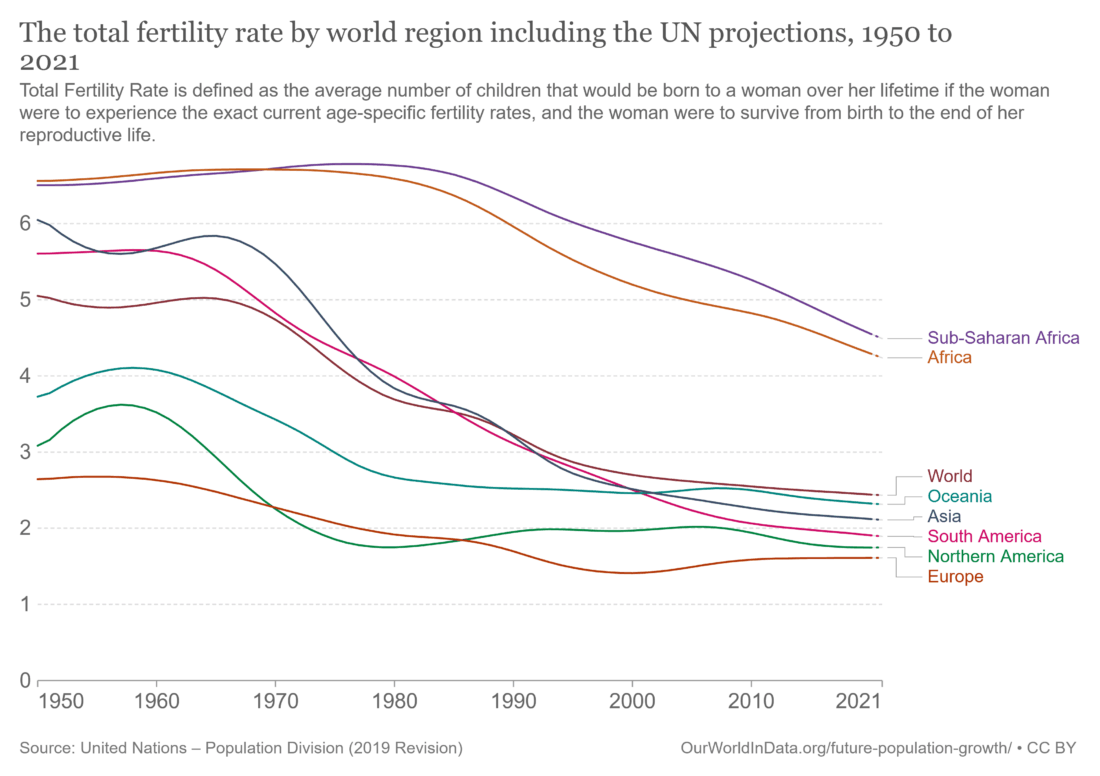

Figure 1 – Predicted population plunge, 2025-2050 (Source: UN, World Population Prospects 2024, via  Figure 1 – Fertility rate by world region, 1950 -2021 (

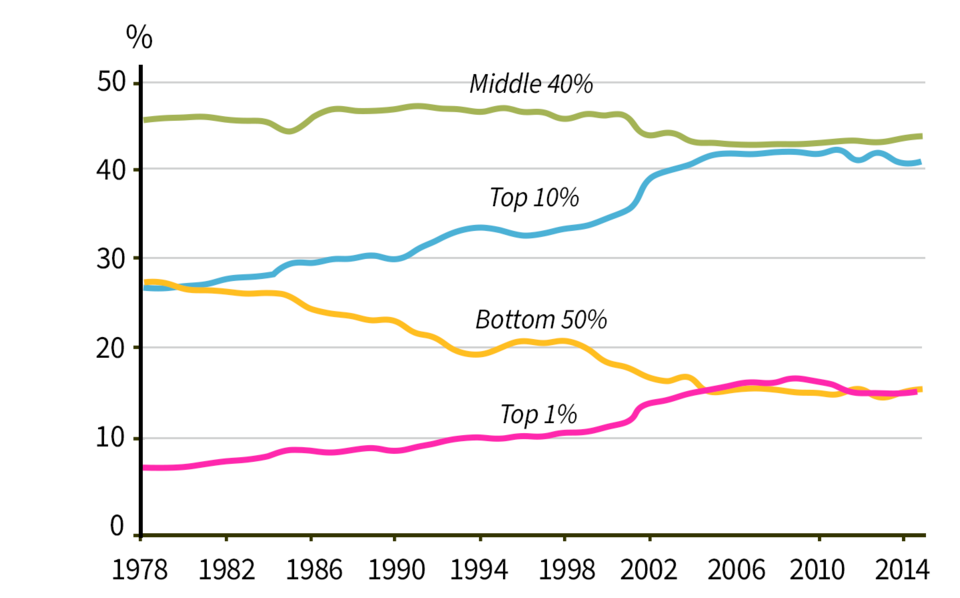

Figure 1 – Fertility rate by world region, 1950 -2021 ( Figure 2 – Wealth distribution in China (Source:

Figure 2 – Wealth distribution in China (Source:

Figure 5 –

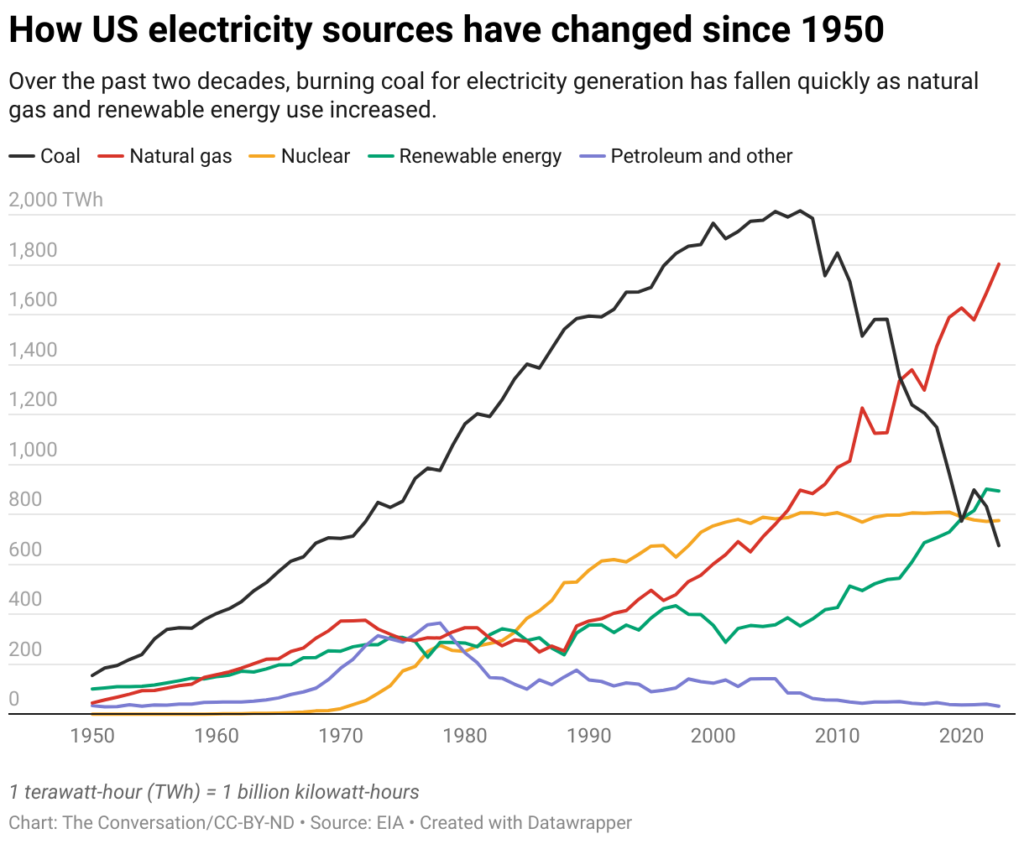

Figure 5 –  Figure 1 – Source: The Conversation)

Figure 1 – Source: The Conversation)