In the last few blogs, I tried to advocate pairing activities that focus on the Holocaust with those focused on future global threats. I defined global threats based on my perspectives and sort of cherry-picked some of them to mimic my own life. The objective in doing so was summarized in an earlier blog, “What Are We Trying to Teach Our Children?” (June 11, 2024). The essence of my argument is summarized in the paragraph below:

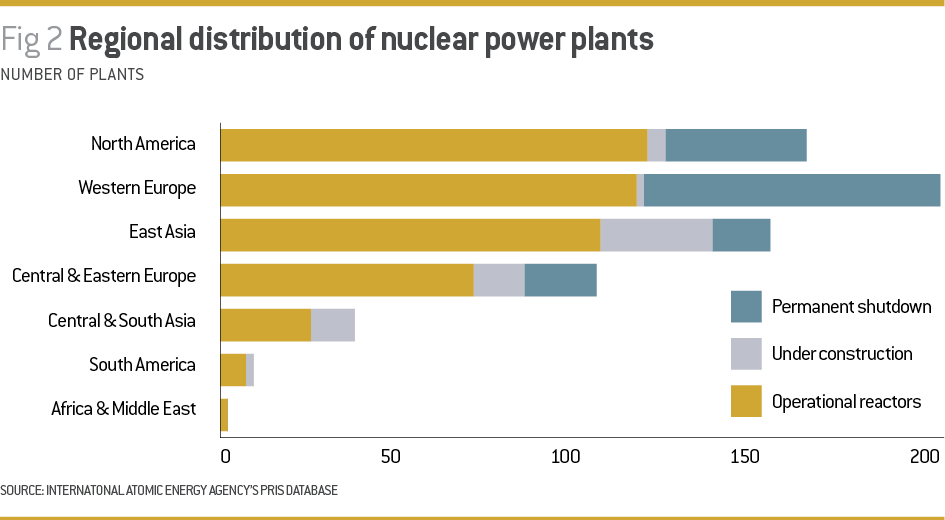

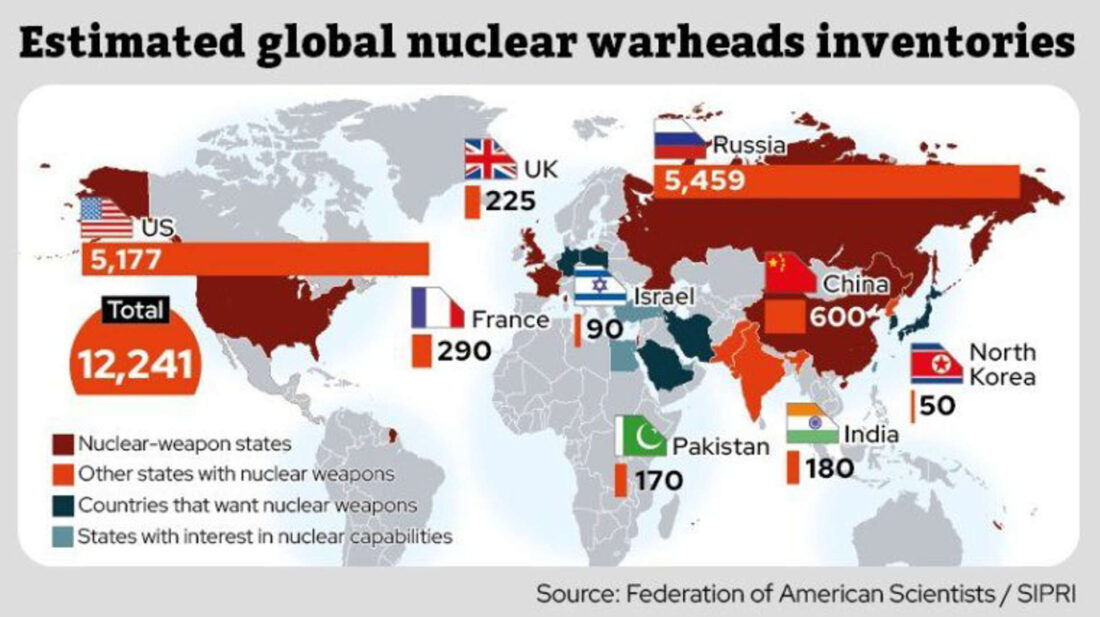

As I have tried to show in the more than 12 years that I have been writing this blog, humanity is in the middle of at least 5 existential transitions; all of these started around WWII. They include climate change, nuclear energy, declining fertility, global electrification, and digitization. These transitions started around the time that I was born, but they will hopefully last (if some of them do not lead to extinction in the meantime) at least through the lifetime of my grandchildren (I call this time “now” in some of my writing).

My definition was subjective. Only three of these transitions are existential threats: climate change, nuclear war, and uncontrolled digitization (especially AI). The other two (global electrification and the constant decline in fertility) are development trends that reflect humanity’s choices. There are many who study global threats in much more depth. Recently, Wikipedia summarized these efforts with more than 100 references. I strongly recommend that you read the full entry. Two paragraphs in the Probability section are especially instructive, and I cite them below:

Experts generally agree that anthropogenic existential risks are (much) more likely than natural risks.[16][13][17][2][18] A key difference between these risk types is that empirical evidence can place an upper bound on the level of natural risk.[2] Humanity has existed for at least 200,000 years, over which it has been subject to a roughly constant level of natural risk. If the natural risk were sufficiently high, then it would be highly unlikely that humanity would have survived as long as it has. Based on a formalization of this argument, researchers have concluded that we can be confident that natural risk is lower than 1 in 14,000 per year (equivalent to 1 in 140 per century, on average).[2]

Another empirical method to study the likelihood of certain natural risks is to investigate the geological record.[16] For example, a comet or asteroid impact event sufficient in scale to cause an impact winter that would cause human extinction before the year 2100 has been estimated at one-in-a-million.[19][20] Moreover, large supervolcano eruptions may cause a volcanic winter that could endanger the survival of humanity.[21] The geological record suggests that supervolcanic eruptions are estimated to occur on average about once every 50,000 years, though most such eruptions would not reach the scale required to cause human extinction.[21] Famously, the supervolcano Mt. Toba may have almost wiped out humanity at the time of its last eruption (though this is contentious).[21][22]

The future is never certain. One common way to try to predict it is through computer simulation. One recent attempt by people who make their living doing so refers to an old simulation and how it bears out today:

A remarkable new study by a director at one of the largest accounting firms in the world has found that a famous, decades-old warning from MIT about the risk of industrial civilization collapsing appears to be accurate based on new empirical data.

As the world looks forward to a rebound in economic growth following the devastation wrought by the pandemic, the research raises urgent questions about the risks of attempting to simply return to the pre-pandemic ‘normal.’

In 1972, a team of MIT scientists got together to study the risks of civilizational collapse. Their system dynamics model published by the Club of Rome identified impending ‘limits to growth’ (LtG) that meant industrial civilization was on track to collapse sometime within the 21st century, due to overexploitation of planetary resources.

The controversial MIT analysis generated heated debate, and was widely derided at the time by pundits who misrepresented its findings and methods. But the analysis has now received stunning vindication from a study written by a senior director at professional services giant KPMG, one of the ‘Big Four’ accounting firms as measured by global revenue.

The Club of Rome report was mentioned in an earlier blog in a somewhat more “poetic” generalization (December 24, 2024):

Probably the most famous monologue that many of us carry in our heads starts with “To be or not to be: that is the question.” It’s the opening line of a monologue spoken by Hamlet in act III, scene 1, of William Shakespeare’s revenge tragedy, Hamlet (I was required to memorize the speech in high school in Israel). From my present perspective about the coming new year, a generalization of this line from our personal fates to the fate of humanity seems to be in order. The “not to be” part could properly be translated to life extinction. After all, as far as we know, we are alone in this vast universe. The prognosis for extinction is growing. I will mention two related articles here. One is from over 10 years ago and discusses a report to the Club of Rome.

Figure 1 – Global risks landscape: An interconnections map (Source: WEF Global Risks Report 2025)

The picture above is different from my previous descriptions of global threats. It is a map of the global risk perception survey, published yearly by the Swiss-based not-for-profit, World Economic Forum (WEF)—the International Organization for Public-Private Cooperation, founded in 1971. An AI summary (through Google) of the methodology of mapping the risks is shown below:

Global risk reports, such as the widely recognized Global Risks Report from the World Economic Forum, primarily rely on a multi-pronged approach that combines expert insights, perception surveys, and various analysis techniques to assess and prioritize risks affecting the world.

Here’s a breakdown of how these risks are typically estimated:

- Global Risks Perception Survey (GRPS): This survey is a core component of the World Economic Forum’s approach. It gathers insights from a diverse group of experts and decision-makers across academia, business, government, international organizations, and civil society. The survey asks respondents to:

- Assess the likely impact (severity) of global risks over various timeframes (e.g., one, two, and 10 years).

- Consider the potential consequences of a risk arising, including interconnections and potential for cascading crises.

- Predict the evolution of the global risks landscape.

- Expert Consultation and Workshops: Beyond the survey, reports often incorporate insights from a broader network of experts through workshops, interviews, and community meetings. This allows for deeper qualitative analysis and discussions on emerging risks, interdependencies, and potential mitigation strategies.

- Defined Criteria for “Global Risk”: The reports use specific criteria to determine what constitutes a global risk, ensuring a consistent and relevant focus. For example, the World Economic Forum considers factors such as:

- Global scope: Potential to affect at least three world regions on two continents.

- Cross-industry relevance: Impact on three or more industries.

- Uncertainty: Uncertainty about how the risk will manifest and the magnitude of its impact.

- Economic or public impact: Potential for significant economic damage or major human suffering.

- Multi-stakeholder approach: Complexity requiring collaboration across various stakeholders for mitigation.

- Risk Analysis and Prioritization: Once risks are identified, they are analyzed and prioritized based on their likelihood and potential impact. This often involves:

- Risk Matrices/Heat Maps: Visual tools plotting likelihood and impact to prioritize risks, according to Number Analytics.

- Risk Scoring: Assigning scores to risks based on likelihood and impact for numerical prioritization.

- Other techniques: Decision trees, sensitivity analysis, Monte Carlo simulations, says Number Analytics.

- 5. Utilizing Additional Data Sources: Reports may also draw on other data sources to complement the GRPS findings, such as the Executive Opinion Survey for national-level risk perceptions, providing a more comprehensive view of risks across different scales.

This is a map of what “important” people think about global threats. It is not explicitly addressed, but since many of these important people are politicians, it is not far-fetched to expect that many of these threats are highly subjective. However, what is amazing (to me) on the map is the strong connectivity between the threats. This connectivity is likely to be retained no matter what those prospective global threats may be.

One important aspect of this map is that many of the listed threats would be considered by the present US administration to be DEI (diversity, equity, and inclusion) issues. I believe these would include: inequality, societal polarization, online harms, erosion of human rights, involuntary migration or displacement, and talent and labor shortage. It is not out of line to think that in today’s environment, a survey like this would not enjoy the support of the US federal government.

A good example of how administrations can impact the publishing of future threats is the presentation of the Global Trends 2035 report, which I described in the May 23, 2017 blog, a few months after the inauguration of the first Trump administration. A paragraph from that blog is given below:

What is Global Trends?

Every four years since 1997, the National Intelligence Council has published an unclassified strategic assessment of how key trends and uncertainties might shape the world over the next 20 years to help senior US leaders think and plan for the longer term. The report is timed to be especially relevant for the administration of a newly elected US President, but Global Trends increasingly has served to foster discussions about the future with people around the world. We believe these global consultations, both in preparing the paper and sharing the results, help the NIC and broader US Government learn from perspectives beyond the United States and are useful in sparking discussions about key assumptions, priorities, and choices. From this “introduction,” two key statements seem informative: that the timing coincides with newly elected administrations and that it is meant to foster discussion. From these, I surmised that this was probably not the original report that I saw and downloaded.

Back to what we are trying to teach our children. I am trying to expand “never again,” by connecting the atrocities of the Holocaust with future existential threats, as an antonym of MAGA (Make America Great Again). The reflection is designed for younger generations to learn from the Holocaust, a globally accepted horrific past, to recognize future existential threats and learn how to mitigate them.

Figure 1 – Diving in the Great Barrier Reef more than a generation ago (I was 60, my wife 50+)

Figure 1 – Diving in the Great Barrier Reef more than a generation ago (I was 60, my wife 50+) Figure 2 – Bleached coral in the Great Barrier Reef

Figure 2 – Bleached coral in the Great Barrier Reef Figure 3 – Bleached coral in Belize (photographed by my wife and me in 2003)

Figure 3 – Bleached coral in Belize (photographed by my wife and me in 2003) A young visitor at the Peace Memorial Park in Hiroshima

A young visitor at the Peace Memorial Park in Hiroshima

(Source:

(Source:

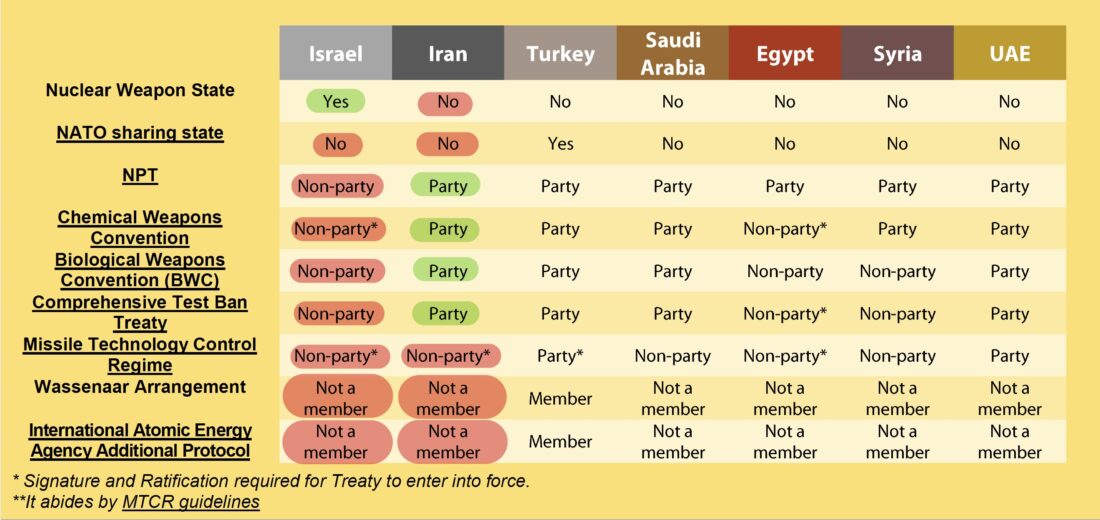

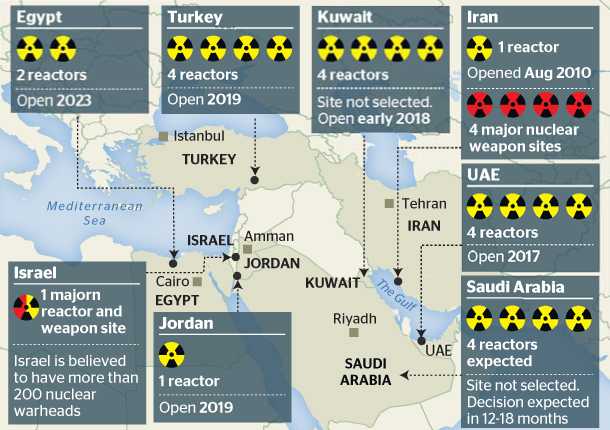

Figure 1 – Map of nuclear reactors and weapons in the Middle East (Source:

Figure 1 – Map of nuclear reactors and weapons in the Middle East (Source: