In the previous blog (February 25, 2013), I focused on K-12 school standards. I emphasized the difficulty in using such standards to ensure that graduates are able to understand and exercise their vote on issues that require collective action, such as energy use and climate change.

As it turns out, I am certainly not the only one concerned about this issue. This semester at Brooklyn College, I have started teaching a new course that focuses on Physics and Society. The students’ inquiries will be posted on an open blog, inviting comments both from other students and from the world at large. We will then discuss them in class. One of the students in the course, Ms. Jenna Peet, posted her first blog on education. The blog was triggered by a short article in a recent issue of Scientific American (the Forum section of the March 2013 issue) by Dennis M. Bartels, the Executive Director of the Exploratory Museum in San Francisco. I am a subscriber, and just received the issue, but I had so far missed this article, and I am thankful to Jenna for the referral. The title of the article is “What is the Question? Critical thinking is a teachable skill best taught outside the K-12 classroom.” The article starts with the following two sentences:

A democracy relies on an electorate of critical thinkers. Yet formal education, which is driven by test taking, is increasingly failing to require students to ask the kind of questions that lead to informed decisions

The rest of the article focuses on the premise that some skills are better suited to be taught outside the classroom. The concrete example discussed is a controlled attempt to answer the question “what type of ecosystem supports eagles.” The article makes the point that museums’ settings are more suitable for accomplishing such an objective.

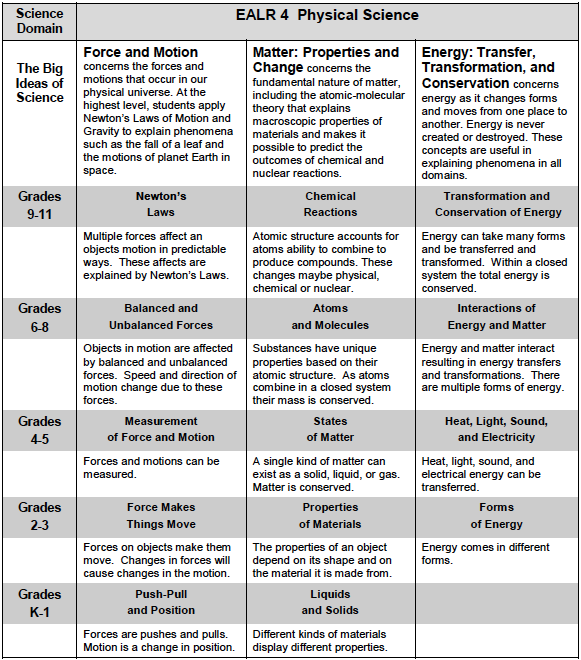

As was discussed in the last blog, federal attempts to make a national standard are a work in progress. All states have standards at least in core subjects. I have chosen the Washington State report on science standards as an example. The standards are partitioned by grades, methods (systems, inquiry, applications, etc..) and disciplines (Physical Sciences, Earth and Space Science and Life Science).

Mathematical standards are mentioned separately, with attempts to use them to support appropriate science standards in the higher grades.

A typical result for the Physical Science is shown in the table below:

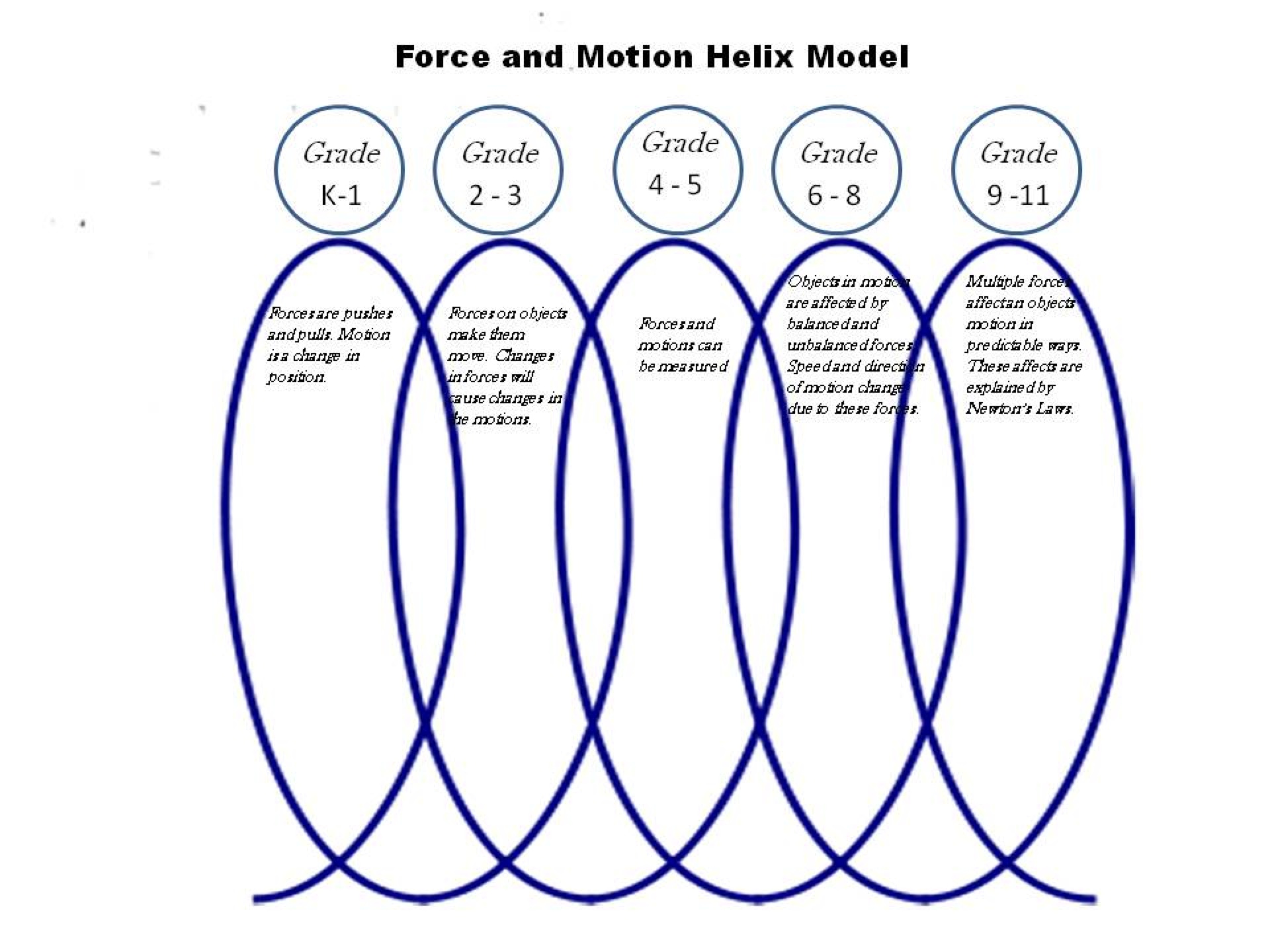

The helical structure of Force and Motion through the grades is shown in the graph below. It is typical of most of the entries.

By the time that the student finishes high school, (s)he will be familiar with Newton’s laws, as well as likely being familiar with other laws and facts. However, as Dennis Bartels mentioned, it doesn’t look like (s)he will be learning to ask questions and search for the answers. When the student comes to Brooklyn College, regardless of whether (s)he majors in Physics (the next blog will focus on the General Education program in Brooklyn College) (s)he will study Newton’s Laws again. Unfortunately, I have no way of incorporating Climate Change, Genetic Engineering, healthcare issues and other politically important science-centered topics into such a curriculum.

By the time that the student finishes high school, (s)he will be familiar with Newton’s laws, as well as likely being familiar with other laws and facts. However, as Dennis Bartels mentioned, it doesn’t look like (s)he will be learning to ask questions and search for the answers. When the student comes to Brooklyn College, regardless of whether (s)he majors in Physics (the next blog will focus on the General Education program in Brooklyn College) (s)he will study Newton’s Laws again. Unfortunately, I have no way of incorporating Climate Change, Genetic Engineering, healthcare issues and other politically important science-centered topics into such a curriculum.

By the age that students finish high school, regardless of how they choose to proceed in life, they will be called upon to vote on such issues and collectively determine our future. Dennis Bartels is right- an isolated classroom is not the place where students acquire the skills to ask the necessary questions and look for corresponding answers. Neither is the museum, although both can be partners in this important task. Science museum visitors are a “biased” audience (see the July 9, 2012 blog). The outside world can, however, be brought into the classroom to be fully analyzed.

In previous blogs (June 4 and June 11, 2012) I have referenced examples of teaching models such as the use of paperclips to teach young children about the Holocaust. I wrote that I was searching for the “equivalent” environmental paperclips to teach about issues such as Climate Change – I am still looking. A friend, a grandmother of a 4th grader, gave me a suggestion. It involved her grandson, Chapin. Chapin’s teacher asked the class to come up with a 6-week-long research project. His parents, grandparents and I gave him some initial help in brainstorming, but he had veto power. His chosen project requires him (with some parental help) to map the use of all the light sources in his house, as well as measuring the energy use of all other electrical utilities, using a gadget such “Kill a Watt.” He must then compare his home’s use of electricity with the electricity bill, and suggest saving strategies. Parallel to that he is also reading an online summary of Climate Change that was written for 4th graders. From what I’ve heard so far, the family is having fun with this project. I will keep you posted as I learn more.

What I’m trying to establish here, is that we need a combination of sources for teaching. It is problematic that in the current system, students aren’t learning critical thinking in school. Teaching to the test does not encourage inquisitiveness, which is exactly what we need our future generations to have in plentiful supply, especially if we want new solutions to current and upcoming problems. Schools have their part to play in education (one whose standards will hopefully improve), but in order to maximize student potential and encourage understanding, we need to supplement that role with other sources. This includes institutions such as museums, but it also includes bringing learning home, making it a fun family activity. After all, “It takes a village…”

I just wanted to say that I really enjoyed your site and this post. The way of share yout thought is really amazing and very informative to everyone.

Best Review Website

Thanks for this! We’ve been building an ed resource at http://UniversityWebinars.org too. Bringing together some of the best speech & lecture videos from top universities for use for higher ed faculty, staff, and students. It’s a good free resource for courses, learning, or professional development. Feel free to share or blog it if you find it useful.

-DJ

http://InnovationLearning.org

I think you would really enjoy the book titled The Brain That Changes Itself by Norman Doidge, M.D. He talks about education and the brain it is very interesting. Some amazing schools have been established based off of recent neuroscience research.

As well, a book I have not read yet but that I have seen a documentary on is titled A Mind at a Time by Dr. Levine. I saw the following PBS documentary and it was very informative. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ChEcsUzfUAs It is also related to the wiring of our brains and education.

I cannot help to think that in the same way we are moving towards individualized gene chips that we will move towards individualized education.

Enjoy!