If we agree that we have to start spending money now, in order to minimize future damage from climate change, where should we start: on adaptation or mitigation – or is it a false choice?

Global mitigation seems to be frozen- or at least this can be said of its form as an international agreement to limit emissions of greenhouse gases through energy transition to more sustainable energy sources. Attempts to adapt to future impacts of climate change seem to be on the rise, however, especially in light of the increasingly frequent need to adapt to extreme climatic events (mainly in urban environments). I summarized several of these efforts in the last few blogs – but do we need to change this trend, or continue it?

Adaptation is mostly local, in both its focus and its financing. This necessarily means that the rich can do much more than the poor. In a few days I am leaving to attend a conference in Mauritius. This is an isolated island in the Indian Ocean, about 2000km from the east coast of Africa. After my return, I will report the adaptation efforts of islands such as Mauritius in some detail. I will also try to show how they generate the resources necessary to finance these efforts. This is especially important, as in principle, if this generation of resources is unsuccessful, the poor will (quite literally) sink, while the rich surround themselves with protective walls to isolate them from the rest of the world.

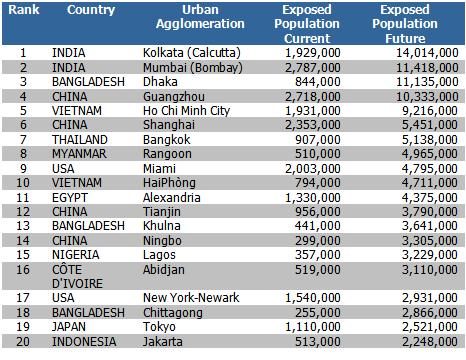

Table 1 – Top 20 cities ranked in terms of population exposed to coastal flooding in the 2070s (including both climate change and socioeconomic change) and showing present-day exposure (Source: Nicholls et al (2007), OECD, Paris)

Table 1 – Top 20 cities ranked in terms of population exposed to coastal flooding in the 2070s (including both climate change and socioeconomic change) and showing present-day exposure (Source: Nicholls et al (2007), OECD, Paris)

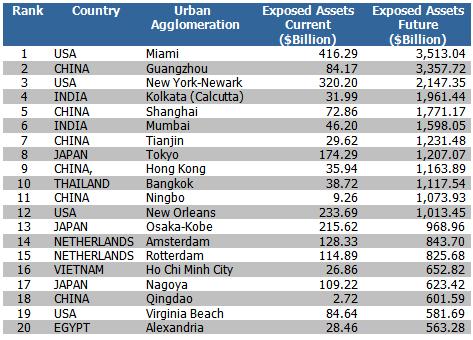

Table 2: Top 20 cities ranked in terms of assets exposed to coastal flooding in the 2070s (including both climate change and socioeconomic change) and showing present-day exposure (Source: Nicholls et al (2007), OECD, Paris)

The two tables above show the top 20 cities ranked in terms of populations and property exposed to coastal flooding. Three out of the 20 are in developed countries in terms of population exposure and 9 out of the 20 in terms of exposed assets. Combining the figures for these top 20 cities, we see an estimated 24 million people exposed to severe flooding (equivalent to flooding zones). Out of these 24 million, 20 million live in what we currently consider developing countries. In the 2070s, the total population in these same cities and zones is estimated to reach 113 million people – out of which, more than 100 million will reside in what we now consider developing countries.

In terms of exposed assets, in the top 20 cities– US$ 2.2 trillion are now exposed– out of which “only” $0.4 trillion are in developing countries. In the 2070s, a total of $27 trillion will be vulnerable, out of which about half will be in cities in what are now considered to be developing countries.

Unlike adaptation, mitigation is global. With more than 70% of the population expected to reside in what we now consider developing countries, the chemical composition of the atmosphere will critically depend on policies in those countries. There is no way to control the chemical composition of the atmosphere without full cooperation of the developing countries. The Kyoto Protocol – the only globally binding protocol to limit greenhouse gases in the atmosphere- has not only excluded developing countries from this commitment, it is now also about to expire, with no agreed substitute in sight. Climate change cannot be solved on a local level; it has to be solved on a global level (see my December 3 blog). The only way to approach a global solution, of course, is to engage developing countries as part of the plan. In order to do that, developed countries must first lead the way and share in the fiscal responsibility; providing resources for adaptation to developing countries. For remediation to succeed, adaptation has to become global, and the efforts to make it so have to start now.

Hi, thanks for this excellent information.

awesome stuff dude, Content is good.