One of the lessons that I learned at the Vancouver conference was to start thinking a bit smaller when talking and writing about the global energy transition. From the beginning, I have referred to this as a stuttering energy transition because of all the obstacles that such a changeover encounters. The transition has to be global; the current trends of energy use affect us all, but the world doesn’t operate globally in a way that policy can be universally enforced. Even our global institutions such as the UN can only enforce behavior through its sovereign member states.

The energy transition, like all such evolutions, involves winners and losers. The clear winners (or so we hope) are future generations, but they don’t have a vote on how we conduct our business. The clear losers are individuals and corporations that have financial stakes in the present energy mix and are going to lose money in the process. In our current system of governance these individuals and corporations have a lot of power to influence governments in sovereign states. Developing countries, which often rely on abundant, low cost fossil fuels as they strive to close the gap between themselves and more developed nations seem similarly likely to lose out. One stumbling block has been that these developing countries which so desire – and deserve – accelerated progress have yet to find proof that alternative fuels can help them achieve that goal. So the global transition is bound to stumble. However, local governments under large sovereign states are starting to develop pressures that might serve as experimental field tests for the broader adaptation of the transition.

A good indicator of local governments’ mitigation efforts against anthropogenic climate change is their steps meant to limit the use of fossil fuels. The most visible part of such attempts is the practice of putting a price on carbon – one form of this is a carbon tax. A carbon tax aims to encourage users to use alternative energy sources by making fossil fuels more expensive. Ideally, these alternative sources emit less carbon, use energy more efficiently and/or are completely non carbon-based (e.g. solar, wind, hydroelectric and biofuel). This method of mitigation changes market conditions in favor of decrease in carbon emissions but it doesn’t put a ceiling on how much carbon can be emitted in total.

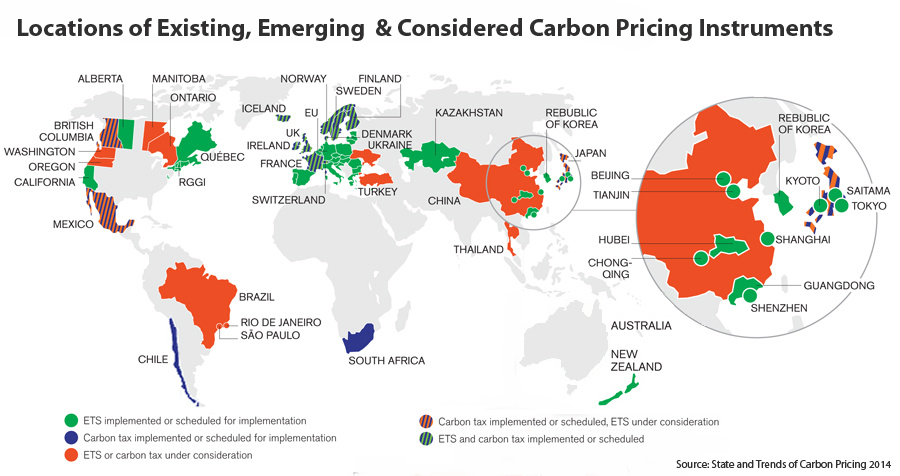

The second method is based on emissions trading (ETS – Emission Trading Systems) or as it is sometimes called, cap and trade. In this system, the authorities set a ceiling for emissions and distribute certificates to corporations and individuals that give them the right to emit certain levels of carbon. These certificates become tradable, so organizations that need to emit more buy certificates from those that plan to emit less. Again, the market determines the price of the certificates. Each method has its own distinct advantages and disadvantages, but implementation of either one indicates serious efforts to confront anthropogenic climate change through limits on carbon emissions. Figure 1 shows the distribution of the global efforts in carbon pricing. The progress of some big sovereign states is obvious, but smaller local governments are important players too. Among the active local governments are many states in federal systems, including most of the Canadian states, all of the states on North America’s West Coast, and the RGGI (Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative) on the East Coast of the US, which includes the states of Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New York, Rhode Island, and Vermont.

The Vancouver conference gave me an excellent view of British Columbia’s efforts. The map also shows some important megacities (cities with greater than 10 million inhabitants) such as Tokyo and many cities in China.

Figure 1 – Carbon pricing around the world

Figure 1 – Carbon pricing around the world

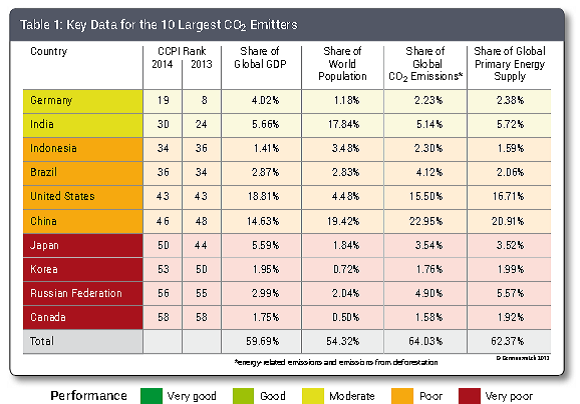

In a previous blog (March 25, 2015) I focused on the 10 largest carbon emitting countries when I talked about 2014’s milestone of reaching a global flat carbon emission in spite of the 3% GDP increase. I am repasting the table, Figure 2, which summarizes the results. In this compilation Canada ranked at the bottom, while it scored 58th on the overall list. The United States is not doing much better, it is ranked 5th in this grouping and 43rd in the overall list.

Canada’s bad performance was not ignored at the Vancouver conference. The second plenary speaker was Kathryn Harrison, a professor of Political Science in the University of British Columbia. She referred to Canada’s performance as deserving of the “Fossil of the Day” award. She also mentioned that Canada was the only country to ratify the Kyoto protocol but then withdraw its involvement when the government changed to a new administration, even as its carbon emission continues to rise.

Figure 2 – Key Data for the 10 largest CO2 emitters (see March 25, 2015 blog for details)

Figure 2 – Key Data for the 10 largest CO2 emitters (see March 25, 2015 blog for details)

Following her talk came a slew of reports about the situation in British Columbia.

British Columbia is already experiencing two immense impacts, both of which have been largely attributed to climate change: major deglaciation and the continuous spread of the mountain pine bark beetle – an insect that destroys the beautiful forests that span the territory. With the loss of these forests comes the corresponding decline of the livelihood that is associated with the lumber industry and tourism.

The deglaciation is already visible. We saw it on top of Mount Grouse (April 14, 2015 blog) – usually in mid-April there is an expected 12ft of snow. As we could see in the photograph, this year it was almost free of snow at that time. Computer simulations predict that both the Rocky Mountain and Pacific Coast ranges will be equally snow free as we approach the end of the century, a result that seems almost independent of the emission scenario we follow. The damage is certainly not limited to aesthetics or even the economics tied to the destruction of recreational ski slopes; it is catastrophic in terms of the fresh water management of the province.

Meanwhile, with the temperature rising throughout the region, the beetle now finds the adjusted environment comfortable year-round. As they adapt to the climate change, the beetles feed on increasingly wide swaths of forest. Once those are destroyed, they simply move on to the next patch.

In western North America, the current outbreak of the mountain pine beetle and its microbial associates has destroyed wide areas of lodgepole pine forest, including more than 16 million of the 55 million hectares of forest in British Columbia. The current outbreak in the Rocky Mountain National Park began in 1996 and has caused the destruction of millions of acres of ponderosa and lodgepole pine trees. According to an annual assessment by the state’s forest service, 264,000 acres of trees in Colorado were infested by the mountain pine beetle at the beginning of 2013. This was much smaller than the 1.15 million acres that were affected in 2008 because the beetle has already killed off most of the vulnerable trees (Ward).

For western Canada, these are not computer simulations, these are imminent threats that must be fought now. Some of the steps that they are taking are innovative enough to be used as examples for the rest of the world. More on that next week.

In order to reduce carbon emission, the government should tax carbon which will reduce its use and put a scale on it. When taxing the carbon it allows the industry to use less which regulates the use and the government can use the money to support other renewable programs that can help reduce climate change.

Great information on B.C. thanks.

This topic made me ever more interested in understanding why our environmental impact and our economical impact conflict. The natural reaction is to say that if we are being productive our economic activity should be improving our living condition. Conversely if we are being wasteful our economic activity will generate additional wasteful burdens on our surroundings. This is precisely what appears to be happening, is it not? Are we not passing the buck to our surroundings instead of addressing our environmentally burdensome techniques? People did not get into positions of power by shying away from responsibility and letting someone take care of things. So why do powerful individuals feel it’s okay to give up respectability for profit? I would venture to say that it’s because everyone is doing it. Kinda like why lying is allowed in ads and copyright infringement/IP theft are rampant on the net. Perhaps we didn’t start this fire but we can not idly sit back and wait for it to reach our homes. As Edmund Burke so brilliantly said “The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to do nothing”.

There are two ways to reduce the use of fossil fuels, that is carbon tax and emissions trade or cap/trade [ETS-Emission Trading System]. Carbon tax is used to increase the price of fossil fuels; so that companies will rely less on fossil fuels. While emissions trade set a ceiling for emissions to allow companies to purchase a limited amount of carbon. Furthermore, according to Figure 2, the largest CO2 emitter is Canada while Germany and India followed by Indonesia, Brazil, U.S. and China are producing less CO2. But Canada is the largest CO2 emitter due to major deglaciation [melting of ice] and an increase in mountain pine bark beetle that destroys forests/trees. Concluding that there are many factors for the increase in CO2 emission that hopefully will be taken care of in the Paris conference in December 2015

In order to reduce the percentage of CO2 emitted into the atmosphere ,there are two way government of certain countries intend to follow or they already following them which are c02 tax and cap and trade.However, it is clear that cap and trade is more effective than CO2 tax as it is offer policy flexibility which is significant for business.Also, cap and trade ensure the environmental positive outcome which people seek to reach.